Israel, Iran, and nuclear risks for the South Caucasus Expert analyses possible fallout

Amid escalating tensions between Israel and Iran, concerns about the safety of nuclear facilities and the potential impact on the South Caucasus region have come to the forefront. Israeli strikes on Iran’s nuclear infrastructure, including the uranium enrichment plant in Natanz, have raised fears of radioactive contamination that could affect neighbouring countries. To shed light on these risks, Caliber.Az spoke with Andrey Ozharovsky, a Russian nuclear physicist and environmental expert specialising in radioactive waste safety. Ozharovsky offers a detailed assessment of the damage, potential hazards, and the broader implications for regional security.

– How dangerous are the consequences of Israeli strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities, particularly for the South Caucasus? There are already conflicting reports about a possible radiation leak at the uranium enrichment plant in Natanz, which came under bombardment.

– The Natanz facility is located 40–50 metres underground. It is currently impossible to assess the extent of damage to its subterranean structures: for obvious reasons, even the Iranian authorities, while in possession of relevant information, will not disclose it so as not to aid the enemy. Meanwhile, neither intelligence reports nor satellite imagery analysis allow for a precise determination of the scale of destruction. However, the mere emergence of reports about a radiation leak suggests that some of the equipment may indeed have been damaged.

Uranium enrichment involves working with a radioactive and chemically toxic substance — uranium hexafluoride (UF₆). At temperatures above 56 degrees Celsius, it turns into a gas and is used in the process of isotope separation. If a leak did occur, it would have involved uranium hexafluoride. Regardless of whether it was enriched, depleted, or natural — this substance is extremely dangerous, primarily due to its chemical toxicity. Upon contact with moisture, UF₆ transforms into hydrofluoric acid (HF), which can cause severe injuries to humans.

However, it is important to note that the leak occurred underground, and Iran is generally a dry country. Due to low humidity and an arid climate, the likelihood of hydrofluoric acid forming and spreading into the environment remains extremely low. If the strike caused a leak from damaged centrifuges, the uranium hexafluoride would have condensed from its gaseous state into a solid and settled right inside the underground facility — on the equipment or structural debris.

– Azerbaijan’s Ministry of Emergency Situations conducted radiation monitoring at 30 control points along the southern border. No violations or signs of radiation leaks were detected. Are there any data from Russian observers?

– First and foremost, it is more accurate to measure not just background radiation, but the concentration of radioactive aerosols in the air. This requires equipment that pumps thousands of cubic metres of air through special filters, where particles settle and are then analysed using gamma spectrometers. In particular, Rospotrebnadzor (Russia’s consumer protection agency) has organised round-the-clock monitoring in the southern part of the Republic of Dagestan. According to observations in Derbent, the radiation situation remains stable. The gamma background level is 0.05–0.06 microsieverts per hour, which corresponds to natural values for the region.

– Which Iranian nuclear facilities could pose a potential threat to the South Caucasus if they were destroyed in a missile strike?

– Indeed, Iran operated a secretive nuclear programme for a long time. For example, the existence of the Natanz facility became publicly known only in the 2000s. This gives reason to believe that the list of nuclear sites available in open sources is incomplete. The good news is that most of Iran’s nuclear facilities are located at a considerable distance from Azerbaijan’s borders and the Caspian Sea coast. The exception is a facility in Iran’s Ramsar, which is relatively close to the Caspian Sea.

It is important to emphasise that the vast majority of Iran’s nuclear facilities are located underground, which significantly reduces the risk of large-scale contamination. Furthermore, most facilities involved in the nuclear fuel cycle do not possess systems capable of releasing radioactive materials into the upper layers of the atmosphere. A much greater threat would be the potential destruction of an operational nuclear reactor — for example, at the Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant. In such a case, a massive release of radioactive materials could occur, similar to the Chernobyl scenario. These emissions can rise kilometres into the atmosphere and spread across vast areas.

– How likely is such a scenario, and what would its consequences be for the South Caucasus?

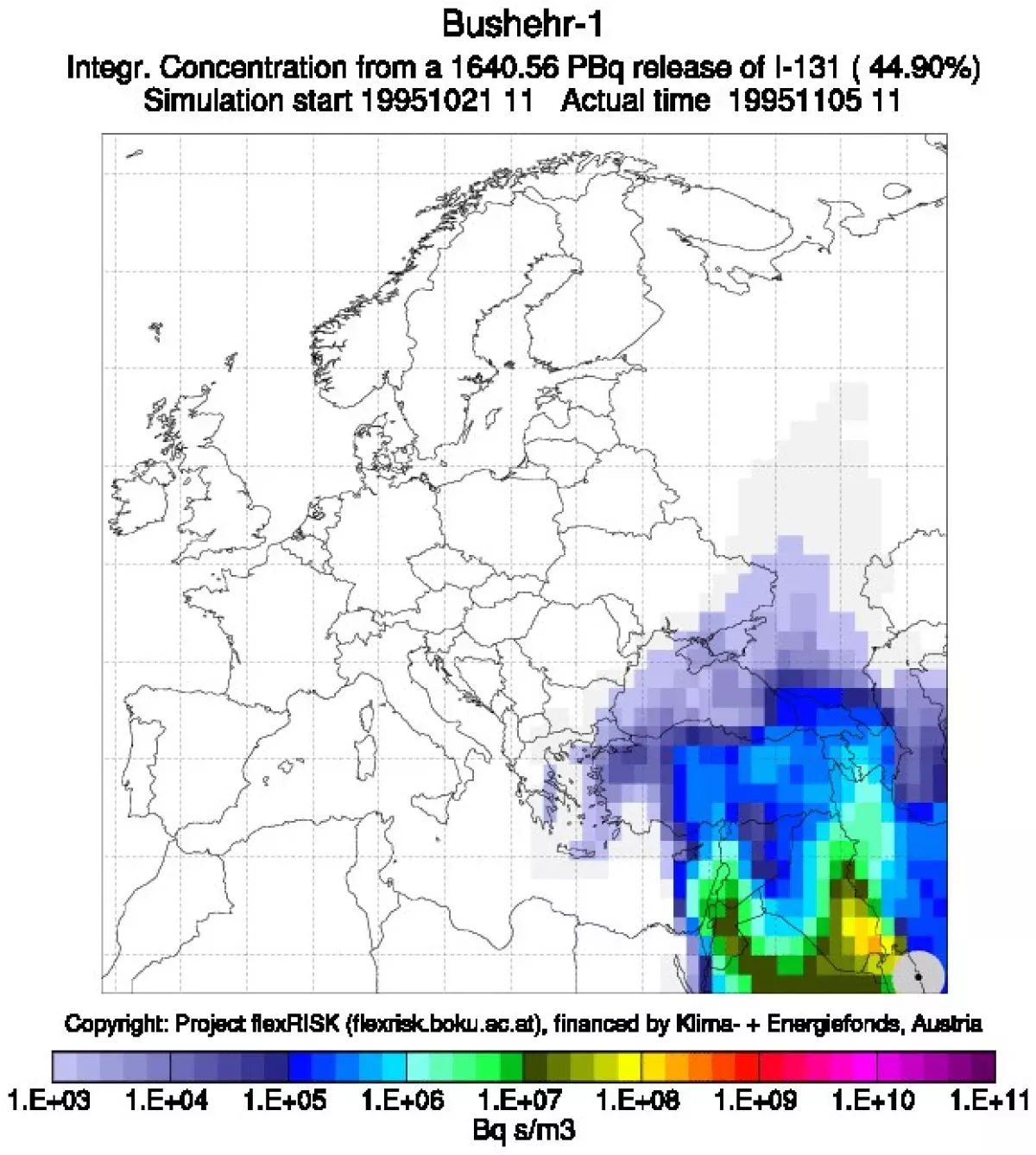

– One would hope that Israel will not attack the Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant. Such an action is not in Israel’s own interest: in the event of an accident, the Gulf states would be the first to suffer. Moreover, the facility is located in the south of Iran, near the Persian Gulf coast, and is far from the South Caucasus. Nevertheless, the risks cannot be completely ruled out. There are, for example, Austrian FlexRisk studies modelling severe nuclear accident scenarios. In some of these, the South Caucasus falls within a potential radioactive contamination zone. These models use a colour scale to indicate danger levels: blue — increased cesium concentration in soil; yellow — threat to agriculture; red — danger to the population, possible evacuation.

But I want to emphasise again: the likelihood of an attack on Bushehr NPP is extremely low, given the political and geopolitical consequences of such a step. And one must not forget that nuclear power plants worldwide remain vulnerable both to military strikes and terrorist attacks. This is one of the systemic and unavoidable risks associated with the use of nuclear energy.