Return of the Pahlavis to Iran: Prospects and consequences Expert opinions on Caliber.Az

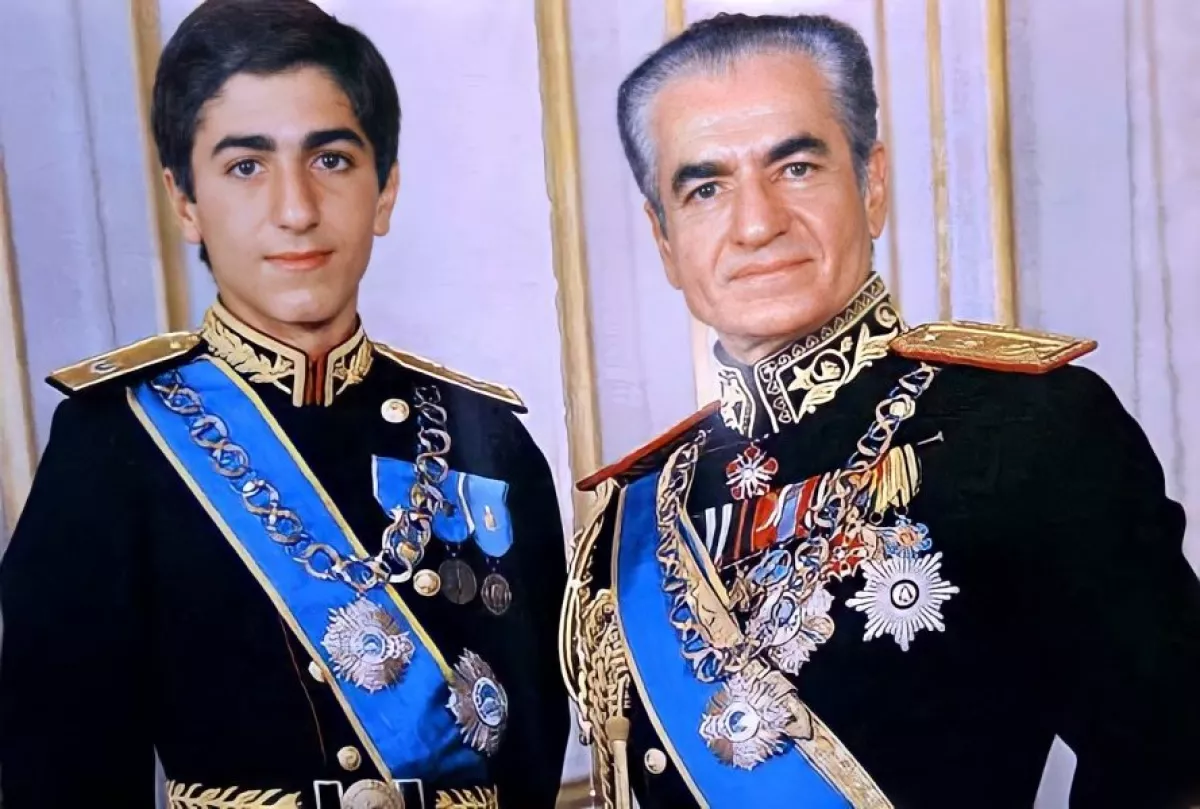

Reza Pahlavi, the eldest son of the last Shah of Iran, is already holding meetings with members of the U.S. Congress and discussing a transition plan in the event of a regime change in Iran, according to Fox News.

The discussions revolve around possible scenarios for Iran's future following the potential departure of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei from power. Planning for a post-conflict political structure is already underway, setting the current situation apart from previous U.S. foreign policy operations, Fox News notes.

How realistic is the restoration of the monarchy in Iran? Would the country’s multi-million, multi-ethnic population be willing to abandon the republican form of government? And if not a monarchy led by a Shah, then what kind of political system could be envisioned? What alternatives exist?

Renowned foreign political analysts shared their views with Caliber.Az.

Georgian political analyst and Middle East expert Vasili Papava believes that a restoration of the monarchy, even in the event of a complete collapse of the Islamic Republic, appears unlikely.

“Monarchist sentiment in modern Iranian society remains marginal and lacks broad support. Although certain circles feel nostalgic for the Pahlavi dynasty’s era—associated with modernisation and economic growth—many Iranians are reluctant to return to the past, remembering the negative aspects of that time, such as corruption, social inequality, and authoritarianism.

The political situation in the country today is complex, and the idea of restoring the monarchy is seen more as an attempt at historical revenge. Domestic attitudes are diverse, and monarchists do not represent a dominant political force. While external players may consider monarchy as a potential stabilising option, the idea does not enjoy widespread support within Iran.

There is no strong and unified opposition in the country capable of offering a viable alternative to the current regime, including a monarchist one. Existing opposition groups are fragmented, and many advocate for secular or democratic forms of governance, rather than a return to monarchy.

However, monarchist sentiment is noticeable among segments of the youth. Some young people associate the restoration of the monarchy with hopes for improved relations with the West and expanded personal freedoms, believing that a return to monarchical rule could facilitate the country's modernisation and open up new opportunities for its citizens.

In the context of Iran’s longstanding confrontation with Israel, any initiatives linked to the Pahlavi dynasty are widely perceived inside Iran as part of a geopolitical project backed by the West and the Israeli lobby.

During the reign of the last Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Iran and Israel maintained close diplomatic, economic, and military ties—a stark contrast to the hostile policies of today’s Islamic Republic of Iran.

However, the Pahlavi dynasty—particularly Reza Pahlavi—faces significant distrust both inside the country and among the diaspora. His contacts with Israel and efforts to secure foreign backing are seen by many as politically misguided, undermining the legitimacy of the monarchist project. Critics argue that such actions only reinforce the Iranian authorities' narrative that portrays monarchists as tools of Western and Israeli interests aimed at destabilising Iran.

Given the country’s complex ethnic and political landscape, as well as fears of potential fragmentation, most internal and external stakeholders lean toward preserving national unity through a gradual transition to more modern forms of governance—rather than pursuing the restoration of the monarchy.

Despite the symbolic appeal of monarchy to some nationalist-leaning groups, experts view its restoration as a utopian project that does not align with the realities of contemporary Iranian society and its confrontation with Israel.

In this context, the marriage of Princess Iman Pahlavi—granddaughter of the last Shah of Iran—to American businessman Bradley Sherman, who is of Jewish heritage, sparked lively debate online.

This interfaith union is not seen merely as a personal matter, but rather as yet another link in what is perceived by some as a broader Western and Israeli project aimed at promoting a monarchical restoration. According to the expert, this only deepens public scepticism about the likelihood of the Pahlavi dynasty returning to power,” the expert said.

In his view, the majority of Iran’s population—given its large size and multi-ethnic composition—is unlikely to support abandoning the republican form of government.

“People are more inclined toward the idea of a secular and democratic system rather than a monarchy, which is often associated with foreign influence.

Moreover, monarchists are frequently perceived as being aligned with external interests, which undermines their legitimacy in the eyes of the public.

A Western-style democratic model is virtually impossible in Iran due to the country’s historical, cultural, and religious context. Its multi-ethnic and multi-confessional society, the deep-rooted presence of Shia Islam, and the historical role of strong central authority as a guarantor of national unity all present significant barriers to liberal democracy.

The Shah’s policies of Westernisation, secularism, and repression in the 20th century provoked strong resistance from the Shia clergy and broader society, ultimately leading to the 1979 revolution. The Islamic Republic, founded on a theocratic model and the institution of Velayat-e Faqih (Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist), emerged as an ideological and structural alternative to Western influence, providing a framework for stability.

An alternative to both monarchy and the current theocracy could be a hybrid constitutional republic with an Islamic character. In such a system, the Supreme Leader would retain a symbolic and arbitrating role—similar to a constitutional monarch—but with limited powers. Actual legislative authority would rest with an elected parliament representing the country’s diverse ethnic and religious groups, including Persians, Azerbaijanis, Kurds, and Sunnis.

Federalisation could accommodate Iran’s regional diversity and reduce the risk of separatism by granting autonomy to ethnic and cultural groups. However, foreign actors would inevitably exploit such developments, using issues of autonomy and minority rights as leverage to pressure the government.

Aware of this, the current regime would view any proposals for federalisation with deep suspicion, fearing a loss of control. A more feasible approach might involve the gradual introduction of secular laws in areas such as the economy and education, while maintaining Islamic norms in the social sphere—thus easing potential resistance from the clergy.

Nevertheless, implementing such a model faces serious challenges: resistance from entrenched elites, the risk of social division, and the threat of fragmentation—similar to what has occurred in Iraq or Syria. Without a strong central authority, any move toward decentralisation must be approached with extreme caution and gradual implementation,” Papava believes.

Executive Director of the Centre for Middle East Studies in Kyiv, Ihor Semyvolos, believes that for now, this resembles “dividing the skin of a bear that hasn’t been killed yet,” although the Shah’s son’s political activity is understandable—he needs to stay engaged so as not to be sidelined when the moment arrives.

“The post-conflict planning for Iran that you mentioned is standard practice for such institutions, as is the development of transition scenarios. However, in reality, events rarely unfold as anticipated, since forecasting under such conditions is extremely difficult.

As for the restoration of the monarchy: from the perspective of some analysts in Washington, a return to monarchy might seem logical, considering Iran’s political tradition of centralised, one-man rule.

Although Reza Pahlavi swears he supports democracy and a republican form of government, many Iranian opposition figures remain unconvinced. The failed coalition of opposition forces is still fresh in people’s memory, and Pahlavi—or his inner circle—is often blamed for its collapse, allegedly trying to dominate the movement and shift the focus onto himself.

In fact, it is Pahlavi’s entourage that draws the most criticism. They are accused of holding far-right views and plotting to eventually crown the Shah’s son,” the analyst said.

As for the republic, Semyvolos notes that Iran already functions as one—in parallel with the principle of Velayat-e Faqih introduced by Khomeini. “With a bit of imagination, this system resembles the guiding and directing role of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union,” he says. “So, if political reforms were to abolish the Velayat-e Faqih framework, the transformation of the Islamic Republic into a secular state is quite conceivable.”