Iran’s hijab debate: between secularism and conservatism Political analysts on Caliber.Az

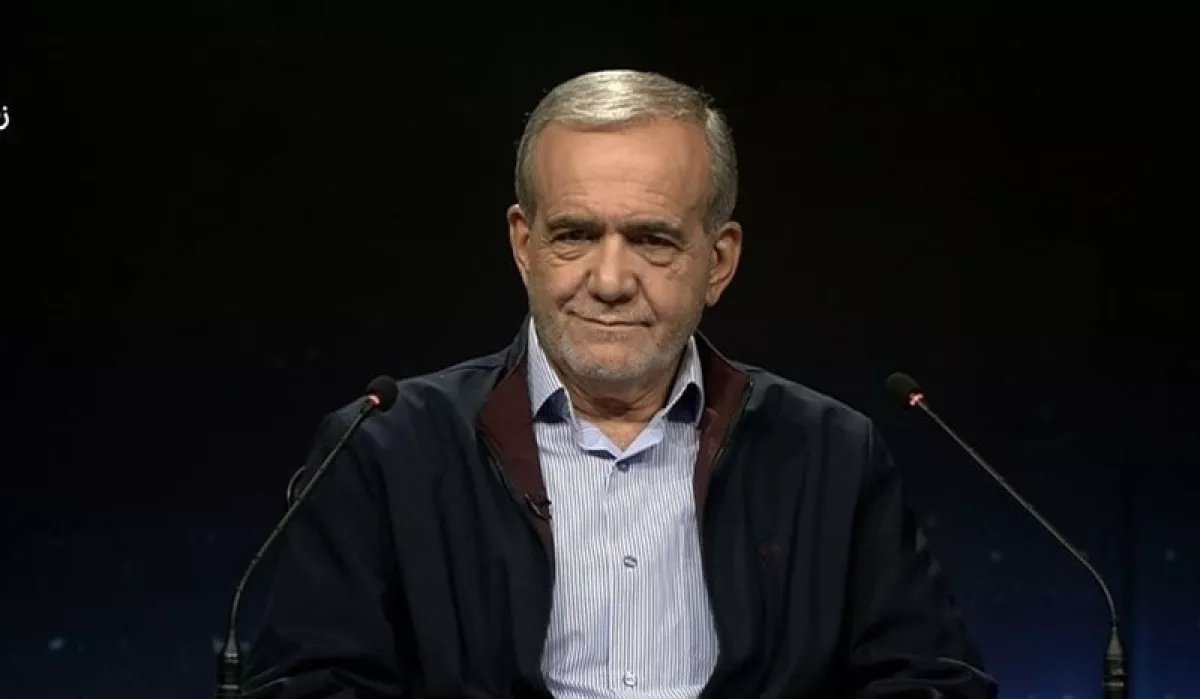

Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian spoke out against forcing Iranian women to wear the hijab and expressed support for their right to choose. “Human beings have a right to choose,” he said in an interview with NBC’s Nightly News host Tom Llamas, responding to a question about Mahsa Amini, whose death three years ago after being detained by Iran’s morality police sparked nationwide protests.

“We didn’t have appropriate management of our internal issues and implementation,” the Iranian president added, explaining the situation. Pezeshkian also noted that the rest of the world was “blowing things out of proportion”: “Of course, each human life is priceless. [But] on a daily basis, hundreds of people are being killed in Lebanon, in Gaza, in all over Palestine, in Yemen and Syria, yet no one bats an eye? Why? These are less human beings?”

What does Pezeshkian’s statement imply? Is it merely a personal viewpoint, or does it signal an intent by the Iranian leadership to repeal strict hijab laws? How feasible is such a move? Caliber.Az asked Iranian political analysts to answer these questions.

Political Analyst, Former Azerbaijani Ambassador to Iran, Javanshir Akhundov, believes that the Iranian president’s statement that wearing the hijab is “a matter of choice” reflects not only his personal views but also the position of the entire reformist wing of Iran’s elite, which he now effectively leads. This camp includes prominent figures such as former Presidents Khatami and Rouhani, as well as Mir-Hossein Mousavi, the former prime minister who spent 12 years under house arrest without any charges. According to the expert, this wing is currently shaping a more pragmatic and constructive approach to social issues, in contrast to the ultraconservatives.

“Just six months ago, ultraconservatives were trying to push a law through parliament to tighten hijab regulations. The law proposed severe penalties: fines, prison terms, and pressure on women in every possible way. But under the influence of Pezeshkian and the reformists, this bill was rejected. The president’s words in the NBC Nightly News interview merely confirm his line: Iran is gradually easing measures against women. In Tehran, one can already notice that women feel freer, and in the northern districts of the capital and shopping centres, women without hijabs can be seen. However, in universities and government institutions, the rule still remains mandatory,” Akhundov noted.

At the same time, the political analyst considers it unlikely that a law formally enshrining women’s right not to wear the hijab will be adopted: “Such a step is impossible at the moment. But gradual relaxations will occur, because life in the country and the socio-economic reality are pushing in that direction. This process is very complex: conservatives retain significant resources—financial, security, and repressive—and they understand that liberalisation could lead to increased public pressure. Therefore, they will continue to resist.”

According to him, internal changes in Iran cannot be viewed in isolation from the broader foreign policy context.

“The latest statements by Pezeshkian on the nuclear programme indicate that one should not expect a compromise with the West: the latter demands a complete abandonment of nuclear ambitions, which the Iranian leadership refuses to accept. This is precisely why, on September 28, strict international sanctions against Iran were reinstated, binding on all countries and hitting the Iranian economy in the harshest way. Already, the treasury is empty, inflation is extremely high, and the sanctions pressure has cut off the country’s access to investments, technology, and external markets.

All of this collectively pushes the leadership toward necessary measures, such as easing social restrictions, including those related to the hijab. Simply put, they cannot manage the situation otherwise. Everything is interconnected. One cannot isolate a single factor, whether it is the hijab issue or the nuclear programme. Domestic policy, the economy, social life, and foreign relations form a single fabric that shapes the current picture in Iran. Easing restrictions on certain issues is not a gesture of goodwill but a forced necessity under sanctions, crisis, and external pressure,” concluded Akhundov.

Meanwhile, Lana Ravandi-Fadai, PhD in History, Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences, is confident that Pezeshkian is aware that the conservative bloc within the Muslim government will never allow the mandatory hijab to be abolished.

“The president talks about this, first of all, to increase his popularity among the liberal-minded segment of Iranian society. But I believe he himself does not expect the mandatory hijab to be repealed. By making such loud and unrealistic statements, his goal is more likely to ensure that women and girls are, at the very least, not beaten for refusing to wear the hijab and that violence is not used against them. Unfortunately, such cases do occur. In practice, this means that in the most secular urban areas, the police will turn a blind eye to women not wearing the hijab (which is already largely happening in the northern districts of Tehran). And if someone is detained, it will likely be limited to a fine or a warning, but violence will no longer be used. I believe this goal is entirely achievable,” said Ravandi-Fadai.