Science vs. myths: Caucasian Albania and Armenian pseudo-history Archimandrite Alexy on Caliber.Az

Archimandrite Alexy (Nikonorov), the former rector of the Cathedral of the Holy Myrrh-Bearing Women and long-time head of the Baku Diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church, is a well-known and respected figure in Azerbaijan. He is appreciated not only by parishioners but also by many Baku residents who are far from religion.

Archimandrite Alexy is also a serious scholar who has dedicated many years to studying the history of Caucasian Albania, located on the territory of ancient Azerbaijan and an integral part of its ancestral heritage. For his works, which debunk myths and falsehoods propagated by Armenians, he has become extremely inconvenient for those hostile to Azerbaijan, who attempt to deny the historical past of the country and people.

A year ago, Archimandrite Alexy left Azerbaijan due to his official duties and took up leadership of the Orthodox community in Malta. However, he has not abandoned his scholarly research. His latest works on the history of Caucasian Albania, presented, in particular, at a conference in Rome, sparked a new wave of attacks from Armenian clergy, revanchists, and radicals seeking to tarnish the reputation of the Baku-based cleric.

Caliber.Az contacted Archimandrite Alexy to discuss religion, pseudo-history, and the myths propagated by “armagitprop.”

– What results from your latest research were presented at the scientific conference in Rome? How did people react, particularly the Armenian lobby?

– On April 10, 2025, an international conference on Christianity in Azerbaijan was held at one of the leading Vatican institutions—the Pontifical Gregorian University. Specialists from 15 countries took part in this prestigious forum. I had the honour of serving as the chair of one of the sessions and presenting a report on the Ganja Catholicossate during the Safavid period in the 17th century.

The main source for my research was a recently discovered topographic map in the archives of the University of Bologna, created in 1691 in the capital of the Ottoman Empire. This map allows for a detailed reconstruction of the state of the Caucasian Albanian Church and shows which episcopal residences, monasteries, and shrines were active at the time. Such an approach proved extremely inconvenient for our opponents, who seek to claim that no church other than the Armenian one ever existed in the Caucasus.

At the conclusion of the conference, the Armenian community literally erupted. Without understanding the substance of the event, they tried to label the forum as “unscientific,” “anti-Armenian,” and even “racist.” Of course, this is entirely untrue.

Armenian religious figures, “scholars,” and self-proclaimed “concerned individuals” bombarded Vatican structures for two weeks, demanding that the rector of the university and two prefects of the papal dicasteries be declared persona non grata. And all this simply because they dared to give a platform to non-Armenian Caucasus scholars. It is a true theatre of the absurd, into which, unfortunately, many were drawn.

– How is your service going far from your homeland? How are Orthodox values perceived in Catholic Malta?

– The particularity of serving in Western Europe is that the congregations are mainly composed of migrants far from their homeland. For them, having spiritual support and the opportunity to connect with people experiencing similar difficulties is especially important. The Church becomes a way not to break, to overcome trials, and to preserve oneself, finding in God a source of light that dispels darkness.

As for me, Malta often reminds me of the barren Absheron Peninsula: rocky shores washed by warm seas, and fortifications made of local limestone evoke a special feeling of closeness.

– How are your works received by the Moscow Patriarchate and foreign scholars?

– My first scholarly work on the history of the Caucasian Albanian Church was prepared under the guidance of the respected researcher of Orthodox and non-Chalcedonian churches, Professor Boris Alexandrovich Nelyubov of the Moscow Theological Academy (This refers to Christian churches that did not accept the decisions of the Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD due to Christological disputes. Today, these include the Ethiopian, Coptic, Syrian, Armenian, Eritrean, and Malankara churches — ed.).

As a result of defending my work at the Moscow Theological Academy, I was awarded the degree of Candidate of Theology, equivalent to a European PhD in Theology. To continue research on this topic, His Holiness Patriarch Alexy II sent me to Rome, where I completed both master’s and doctoral programmes.

In 2024, with the support of the Baku International Centre for Multiculturalism, the Institute of History and Ethnography of the ANAS published my book on the Caucasian Albanian Church in English. It was distributed to all major historical and academic libraries worldwide.

Our goal is to present a sober and truthful view of the history of the South Caucasus and its Christian heritage. Armenian propagandists try to impose pseudo-scientific narratives that distort the region’s past.

– Your works are recognised by the scholarly community, which naturally irritates Armenian propagandists. What kind of pressure do you face?

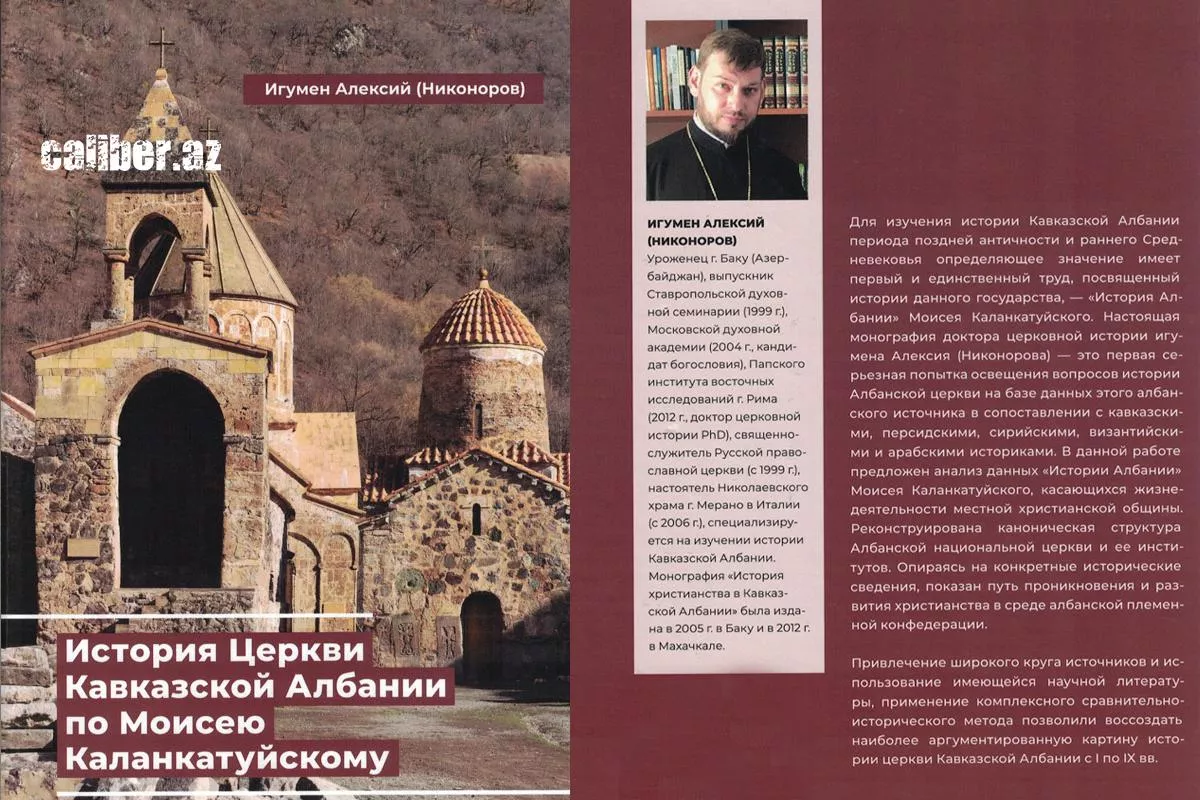

– Since the publication of my 2021 monograph on the work of Moses of Kalankatuy, no serious Caucasus scholar has criticised it. On the contrary, I have received numerous positive reviews.

Attacks come from nationalists, who rely on hackneyed clichés such as “anti-science,” “propaganda,” “undermining interfaith peace,” and the like. They have no scientific arguments, so the whole thing appears almost comical.

– Nevertheless, there are plenty of detractors. The Armenian “Geghard Foundation” accuses you of distorting facts, claiming that “before 1918 there was neither the state of Azerbaijan nor the ethnonym ‘Azerbaijani.’”

– These accusations are made by politicised revanchist circles with little understanding of the region’s history. Claims that the ethnonym “Azerbaijani” did not exist are outright lies.

Since ancient times, the region has been referred to in classical and medieval sources as “Atropatene”—the Pahlavi form of the toponym “Azerbaijan.” In Arabic sources, it is mentioned as the “land of Adharbayjan.” The South Caucasian state of the Atabegs in the 12th–13th centuries was known as “Atabekan-e Adharbayjan.”

If such elementary facts are beyond the authors of the “Geghard Foundation,” perhaps they should remove the word “scientific” from their title. My ecclesiastical superiors undoubtedly have a far higher level of education than the authors of these complaints. In scholarly circles, one responds with arguments, not threats and shouting.

– Why does the Armenian Church take offense when you call it Miaphysite rather than Monophysite? And why do they protest your article on the 17th-century topographic map?

– Questions of dogmatics are complicated for the layperson. Specialists understand that Armenian theology should be classified as Miaphysite. However, in historical literature, the term “Monophysite” has traditionally been used.

The eminent historian V.V. Bolotov wrote: “The Armenians… joined the community of Monophysites, but gained neither honour nor glory there; their position was miserable, and their rites were considered foolish.” It is to the classics, not to me, that such complaints should be addressed.

Regarding my article, sources from the Safavid Empire period (1501–1722) indicate that the beylerbeyliks with centres in Shamakhi, Ganja, Yerevan, and Tabriz were governed by Azerbaijani rulers and were referred to in Persian, Ottoman, and Arabic sources as “Azerbaijani.”

I do not deny that Armenians lived in Yerevan, but their statehood had been lost long before that time. Therefore, at different periods, cities could be referred to as Persian, Ottoman, or Azerbaijani – this is historical reality.

My opponents portray themselves as Don Quixote, forgetting that they are fighting against windmills.