At the bottom of the caste ladder India’s Adivasis on the margins of history

Adivasis are a group of indigenous and marginalised peoples of India who live according to traditional tribal customs. For many years, they have been driven off their land, and today they find themselves caught in the crossfire of an armed conflict.

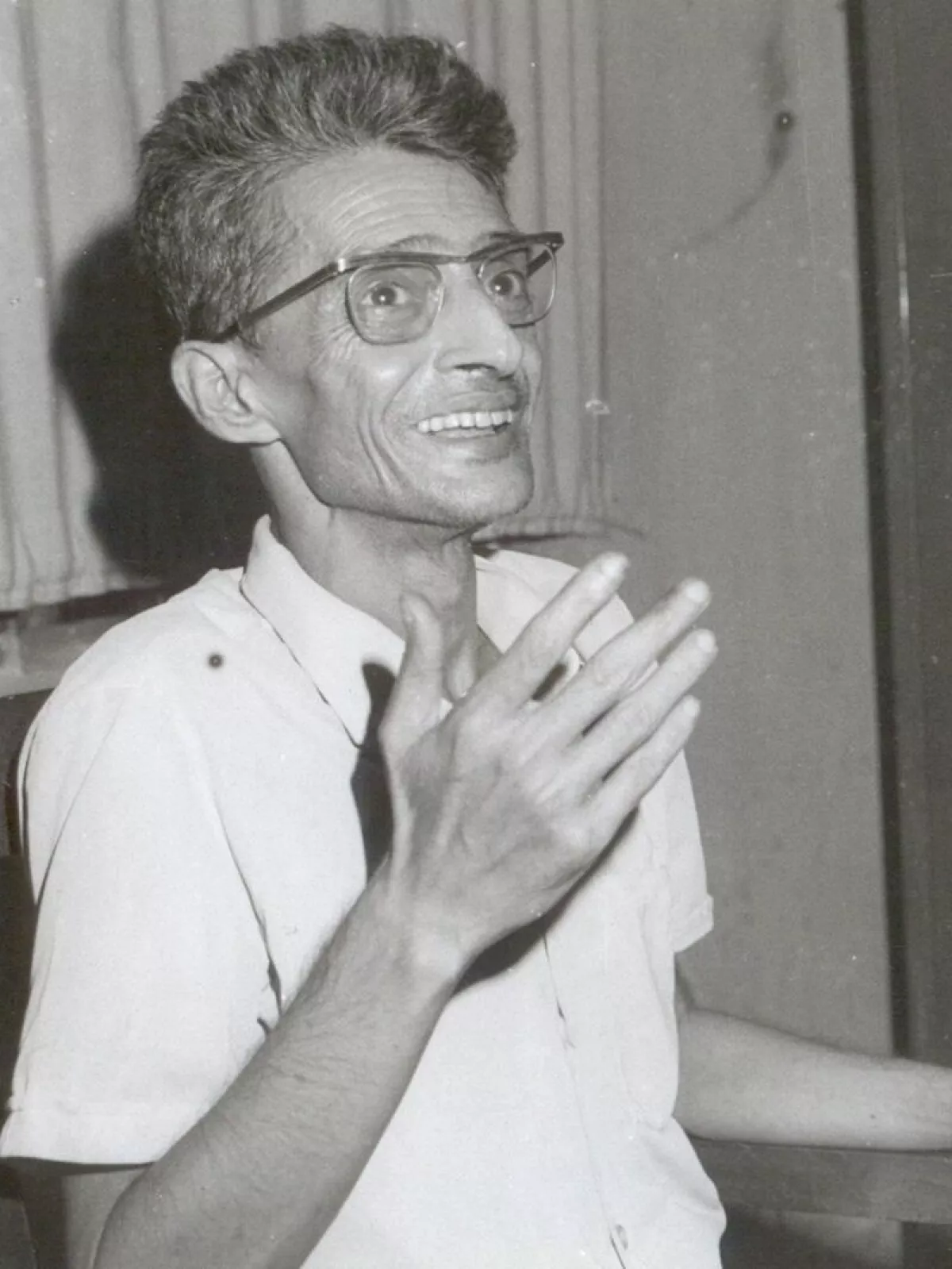

The last battle of "Comrade Basavar"

In the state of Chhattisgarh, Indian government forces eliminated Nambala Keshava Rao, the General Secretary of the Communist Party of India (Maoist), along with 27 people, including members of the Adivasi communities. This is yet another tragic episode in the history of one of the most discriminated ethnic groups in the modern world.

Indian Home Minister Amit Shah announced that on May 21, government commandos killed the leader of the Indian insurgents. The insurgent movement began on May 26, 1967, initiated by Maoists who saw the People’s Republic of China as a model to emulate. Named after the village of Naxalbari in the Himalayan foothills, this guerrilla movement became known as the "Naxalites" and relied heavily on the Adivasi peoples.

The operation to eliminate Nambala Keshava Rao ("Basavaraju", "Comrade Basavar") was carried out in central India. Intelligence managed to track down a rebel unit in the dense forests near the village of Abujhmad in Narayanpur district. The firefight lasted 50 hours. All the encircled Naxalites were killed. Among the dead, in addition to Basavaraju, were other leaders of the Communist Party of India (Maoist) and the People’s Liberation Guerrilla Army.

Shortly before that, the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) conducted a 21-day operation codenamed “Black Forest” on the border of Chhattisgarh and Telangana states.

As a result of the fighting, 214 hideouts were destroyed and 31 insurgents were killed. According to authorities, the total number of Naxalites killed since the beginning of the year has approached 200. These large-scale clearance operations were a response to increased insurgent activity. In January 2025, for instance, eight police officers were killed when their vehicle was blown up by a landmine. For many years, the Maoist movement has been regarded as the most serious internal threat to India's national security.

According to the Home Minister, the elimination of Nambala Keshava Rao could play a key role in weakening the insurgency. However, over nearly six decades of armed conflict, other Naxalite leaders—including the movement's founder, Charu Majumdar—have also been killed, and resistance has continued. New commanders have consistently risen to replace those who fell.

The roots of the Naxalite uprising lie deep in socio-economic realities: poverty, landlessness among peasants, and exploitation of rural populations. Particularly dire is the situation of the Adivasi peoples, whose problems have been ignored by the Indian authorities for decades.

This is why the support for Maoists among the Adivasis does not appear coincidental. Since the uprising began in 1967, indigenous communities have suffered abuse at the hands of the police, forest rangers, and local officials. They were deceived, intimidated, and detained without cause. For the slightest offences, thousands of Adivasis ended up in prison, living under constant pressure and fear.

The Maoists claim to be fighting for land for poor Indian peasants and landless labourers, as well as for indigenous control over ancestral territories and natural resources, which are currently being exploited by foreign companies. Adivasi communities have formed the backbone of the Naxalite insurgency across the so-called “Red Corridor,” stretching across India from Bihar in the east to Tamil Nadu in the south.

Discrimination — “positive” and real

According to the 2011 census, Adivasis made up 8.6% of India’s population. After the Indian subcontinent was conquered by the ancient Aryans some 3,000 years ago, the aboriginal population was pushed into the mountains and jungles and left completely disenfranchised. The newcomers placed them at the very bottom of the social hierarchy. Remnants of this system persist in modern India. In the varna system, the status of the Adivasis is arguably even lower than that of the untouchable castes — they are outside the caste system altogether.

Mahatma Gandhi and the finest leaders of the Indian national liberation movement sought to ensure equal rights for Adivasis and Dalits (formerly “untouchables”) alongside other Hindus. In 1946, Adivasi leader Jaipal Singh Munda told the Constituent Assembly of India: "I take you all at your word that now we are going to start a new chapter, a new chapter of independent India where there is equality of opportunity, where no one would be neglected." But reality turned out to be quite different.

In the Islamic states of the Indian subcontinent, the caste system was officially abolished. However, in India, the socio-economic underdevelopment of many regions has contributed to the preservation of archaic social practices in the public consciousness. Or perhaps — it’s the other way around?

Until recently, most Adivasi tribes subsisted through hunting, gathering, and primitive agriculture. The intrusion of industrial capitalism into India brought new and severe hardships for the indigenous population. Their traditional way of life began to collapse rapidly.

To their misfortune, Adivasis inhabit areas rich in natural resources. Mining, logging, and agribusiness companies began to forcibly displace them, pushing them to resettle in other parts of the country.

This dispossession began during colonial times and continued well into independent India. According to some estimates, the number of people displaced from their ancestral lands since 1947 may be as high as 20–30 million. Even in their new settlements, Adivasis were still treated as second- or third-class citizens.

Today, Adivasis have managed to secure some benefits and quotas from the government. However, they have still not been officially recognised as indigenous peoples. Instead, they have been included in the category of so-called “Scheduled Tribes/Castes,” which are entitled to state assistance. In some states, Adivasis have not even been granted this status.

Scheduled Tribes are allocated a certain number of reserved seats in local self-governing bodies (panchayats), regional governments, and civil service positions. In several states, Tribal Advisory Councils (consultative bodies) have been established. There have also been various educational, cultural, and agricultural programmes, as well as relocation projects.

However, according to official data, the majority of Adivasis (around 60%) remain outside the reach of these initiatives. Over time, these development efforts have stalled. Attempts to change deeply ingrained discriminatory attitudes within India’s caste-based society have also encountered significant obstacles.

Moreover, the job reservations apply only to the nationalised (public) sector; the expanding private sector is not bound by these quotas. Only a small number of Adivasis are able to finish school — and due to poverty and the remote locations in which they live, many are unable to take advantage of university quotas. This creates a knock-on effect: without access to education, members of indigenous communities are often unable to qualify for the government jobs reserved for them.

The rise to power of the far-right Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has, in many cases, worsened attitudes toward indigenous peoples. In several states, nationalists have pursued a policy of imposing Hindu fundamentalism on Adivasis, who traditionally follow their own tribal religions and customs.

However, the tactics of government counterinsurgency forces have recently become more flexible. At CRPF (Central Reserve Police Force) bases deep in the jungles of Chhattisgarh, military doctors now provide free medical check-ups for residents of nearby forest villages. Clothing, food, and medicine are also distributed. At the same time, lectures and film screenings are organised, and a vigorous propaganda campaign is underway to promote the ideology of the ruling Hindu nationalist party among indigenous communities.

Adivasis: India’s “native Americans”

It is often said that the indigenous peoples of these regions are caught between a rock and a hard place — between insurgents and government forces. However, aside from the Naxalites, there are also non-violent social movements advocating for the rights of indigenous peoples — such as the Narmada Bachao Andolan, Niyamgiri Suraksha Samiti, and others.

In one region, Adivasis even formed their own political party — Jharkhand Mukti Morcha (Jharkhand Liberation Front). After decades of persistent struggle, they succeeded in 2000 in establishing a separate state — Jharkhand — which was intended to provide expanded autonomy for the Adivasi population.

Today, India officially counts around 104.3 million Adivasis, a figure comparable to the combined populations of Spain and Italy. However, according to unofficial estimates, the number of indigenous people is significantly higher. The World Bank estimates that 45% of Adivasis still live below the poverty line.

About 95% of the “Scheduled Tribes” continue to live in rural areas and are subjected to severe economic exploitation. Around 10% of Adivasis still lead nomadic lifestyles as hunter-gatherers. For 50% of indigenous people, survival depends directly on the forest and its resources — including the collection of tendu leaves, which are used to make bidi, a traditional Indian cigarette.

Although forests in India are nationalised, they are increasingly being leased to private companies. This commercial exploitation of the jungle has led to a situation where Adivasis can now be fined or imprisoned for gathering forest products in areas they have considered their ancestral homeland for centuries.

Large-scale construction of hydroelectric dams has become yet another challenge for the Adivasis. After the commissioning of the Sardar Sarovar Dam in 2019 — one of the largest in the world — at least 178 villages were partially or completely submerged. Thousands of their residents became internally displaced persons.

According to reports by human rights organisations, Adivasis continue to face discrimination and violence from large segments of Indian society. They remain at the bottom of all socio-economic indicators. Most government development programmes are aimed more at assimilation than at preserving the identity and traditional way of life of indigenous communities. Many of the smaller Adivasi ethnic groups now face a genuine threat of extinction.

The Indian state remains indifferent when it comes not to political correctness, but to questions of land redistribution, or the interests of poor peasants and day labourers.

The number of Adivasis who have received compensation for the land from which they were evicted remains extremely low. Due to bureaucratic delays or other reasons, Indian courts have reviewed only 2% of the claims filed.

In February 2019, the Supreme Court of India, acting under the Forest Rights Act (FRA), ordered the eviction of more than one million people whose claims had been rejected.

“These trends also point to more general institutional and legal inadequacies and the resulting lack of trust the Adivasis have in the Indian state that promises to protect them but practices exactly otherwise…” — such is the grim conclusion drawn by human rights advocates.

As a result of fierce protests, Adivasis were granted a temporary reprieve from further displacement. But the threat of forced eviction still looms over India’s indigenous peoples.