Epstein: Anatomy of institutional paralysis A moment of truth for Western democracies

The release of the "Epstein files" was meant to be a moment of truth—an opportunity for answers and justice. Instead, it produced a paradox: the more details emerged, the less clear the picture became. Documents multiplied, names surfaced one after another, and witness testimonies painted a portrait of horrific crimes. Yet rather than crystallising the truth, the files only deepened the fog. Making them public did not close the case; it revealed, with stark clarity, the absence of mechanisms capable of seeing it through to a proper conclusion.

The “Epstein case” is less about the personality of its central figure than about the way a zone of institutional silence formed around his activities. This was not a mystery in the traditional sense—far too many people held fragments of information. Yet knowledge failed to translate into action. It is here that the uncomfortable truth for Western democracies emerges. And it is not merely about corruption in its usual, obvious form; it is about the system’s profound inability to function when potential offenders possess power, influence, and connections.

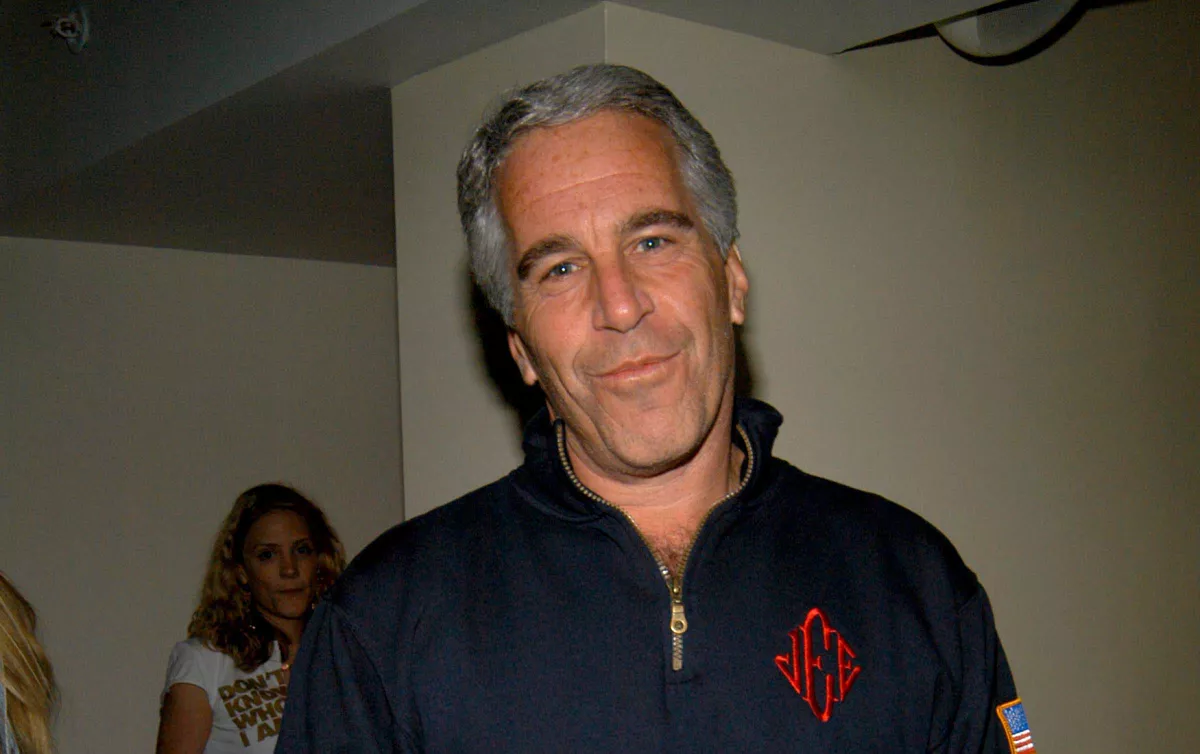

The first accusations against Jeffrey Epstein emerged in the spring of 2005, when the stepmother of a 14-year-old schoolgirl reported to the police that the financier had raped her stepdaughter. The girl had been brought to Epstein’s Palm Beach, Florida, mansion and paid $300 to undress and give a massage to the house’s owner. Police launched an investigation, and in Epstein’s mansion, they discovered hidden cameras and photographs of other underage girls.

A criminal case was opened against the millionaire on charges of coercing minors into sexual acts and engaging in sexual activity for remuneration. In 2008, he pleaded guilty to two charges of soliciting prostitution, paid compensation to his victims, and, by striking a secret deal with prosecutors, received only eighteen months in prison. In other words, the Florida prosecution already had ample evidence at the time—victim testimonies, financial records, and travel logs—all more than sufficient to pursue a serious criminal case. Yet Epstein received a minimal sentence and continued to live according to his usual routine.

This situation is difficult to explain through legal logic alone; it reflects the federal authorities’ unwillingness to get involved in a case that could implicate too many powerful individuals—from American celebrities to Macron and members of European royal families. It is important to understand the nature of this case. This was not a conscious cover-up in the strict sense. It was evasion—each institution focused on its own area of responsibility and saw no sufficient reason to go beyond it. The prosecution treated the case as a local offence. The FBI documented individual episodes but did not attempt to see the bigger picture. Immigration authorities checked entry documents but did not question why underage girls from Eastern Europe or Latin America were entering the country on visas issued through suspicious channels. Banks processed transactions, some of which were clearly illegal, yet they saw no need to investigate the nature of these payments.

This is the real problem. The system did not fail at a single point—it proved structurally incapable of responding to crimes that fell outside standard procedures. Modern Western institutions are built on the principles of separation of powers and specialisation, which ensures efficiency in routine situations but creates blind spots where interagency coordination and the willingness to act against top-down pressure are required. The “Epstein case” fell precisely into such an unreachable zone. It demanded that someone take on the risk of political and reputational consequences. No one was willing to do so.

The immigration aspect is also revealing. Victims were brought into the United States legally—they passed through official checkpoints, their documents were checked, and their presence in the country was recorded. Yet no one asked a simple question: why were fifteen-year-old girls from impoverished areas suddenly able to enter the U.S. on tourist or work visas arranged through intermediaries? Why did their routes repeat, and why did they all end up in the same places? Answering these questions required no complex investigation—only a willingness to look beyond formal procedures.

The banking system is another telling element. Epstein managed enormous sums, and part of that money was used to pay for services that any prudent analyst in a financial monitoring department would have considered suspicious. Regular payments to minors, transfers through offshore structures, property rentals in the names of third parties—all of this left a trail. Yet the banks showed no interest in the nature of these transactions. They simply fulfilled the formal requirements of anti-money laundering regulations, checked the necessary boxes, and moved on. Once again, no one was willing to take responsibility for raising questions about a client who was generating profit.

All of this paints a picture of institutional paralysis, and this is not an abstract problem. It is a direct challenge to the postulate that Western democracies possess institutions strong enough to protect citizens’ rights and freedoms, regardless of the status of the suspected offender. In practice, the reality is very different: these institutions function smoothly only until they confront real power.

This failure is especially striking against the backdrop of the moralising rhetoric of past U.S. administrations, which for decades lectured the world on the rule of law, judicial independence, and the principle that no one is above the law in a democratic society. All of this sounds far more cynical when a case emerges in the United States itself that demonstrates the complete opposite. No one is above the law? Epstein was. And not just him. Those in his orbit—whose names appear in documents, whose connections can be traced through financial flows and witness testimonies—also stood above the law. Because the very institutions tasked with enforcing that law simply washed their hands.

The “Epstein case” exposed a simple but deeply uncomfortable truth: the strength of democratic institutions depends on their willingness to act against pressure. When external influence outweighs that willingness, these institutions cease to be guardians of the letter and spirit of the law and become mere stage props. And this is a far more serious problem than any individual crime, no matter how monstrous. A crime can be investigated, and a criminal can be held accountable and punished. Institutional paralysis, however, is a diagnosis of the system itself, and curing this disease remains a highly elusive prospect.