First Abkhazia, then the trains Tbilisi sets a condition for Moscow

The issue of reopening the railway line through the currently occupied region of Abkhazia has resurfaced, with the initiative this time coming from Russia. However, Georgia has firmly stated a condition for possible reopening: recognition of its territorial integrity and the de-occupation of the territories.

“Work is underway to unblock all disrupted transport routes in the Caucasus, including consideration of restoring railway service between the Russian Federation and Georgia via the territory of Abkhazia,” said Russian Deputy Prime Minister Alexey Overchuk.

According to him, restoring this route is necessary to address the “major task” of strengthening transport and logistics connectivity in the Caucasus, which is “critically important for the peace, stability, and economic prosperity of the peoples of Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia, Iran, Türkiye, and Russia.”

Overchuk added that “the Russian Federation has decided to begin substantive negotiations on restoring two railway sections in Armenia that will connect with the railways of the Republic of Azerbaijan near the village of Yeraskh, as well as with the railways of the Republic of Türkiye near the settlement of Akhuryan.”

However, Georgian officials denied that any negotiations with Russia are taking place. Georgian Railway stated that there are no discussions underway regarding the restoration of railway service through Abkhazia.

“In response to information circulated in the media claiming that the Russian side is considering the possibility of restoring railway links with Georgia via Abkhazia, we clarify: Georgian Railway is not discussing the issue of resuming railway service between Russia and Georgia, and therefore it is completely unclear to us why this matter has appeared on the agenda,” the agency said in an official statement.

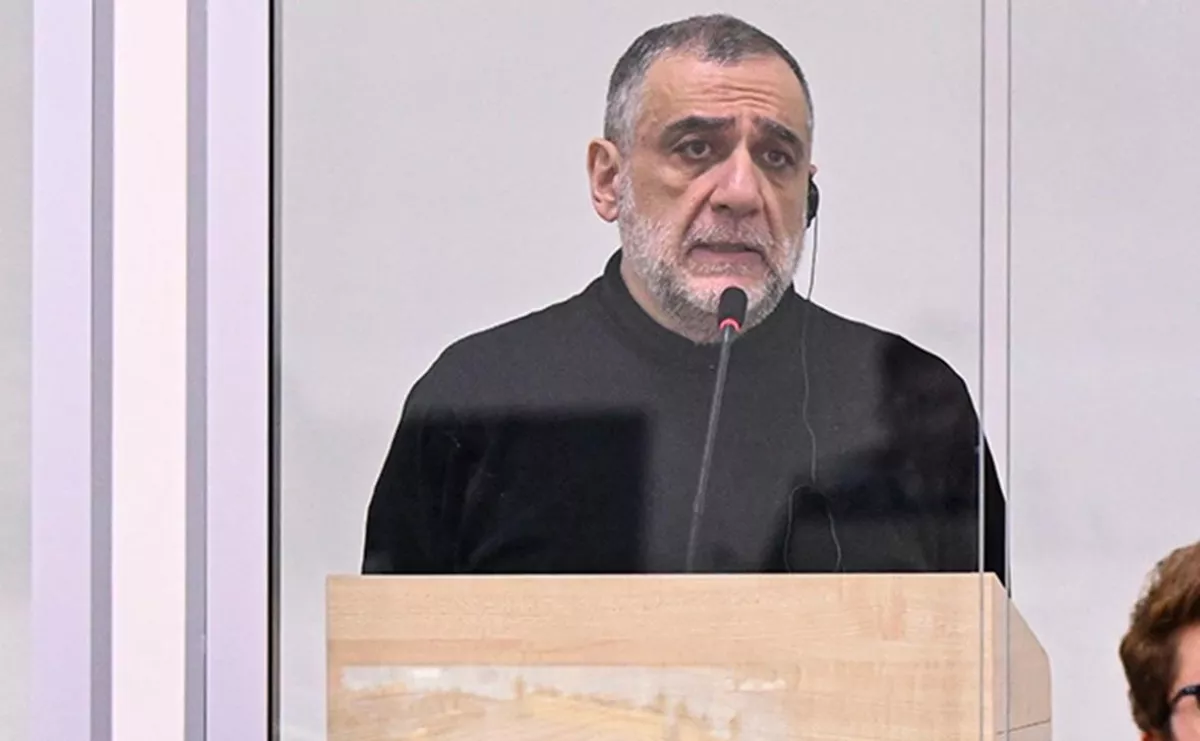

The absence of negotiations with Moscow on the Abkhaz railway route was also confirmed by Speaker of the Georgian Parliament Shalva Papuashvili. According to him, discussion of both railway links and the restoration of relations is possible only under one condition — ensuring Georgia’s territorial integrity.

“I don’t know who they are talking to — they’re not talking to us; perhaps they’re talking to each other. …Russia already has a railway service with the occupied territory, so there is nothing new here. As for the territory where the jurisdiction of the Georgian authorities is exercised in full — do you really think a train could pass now without anyone asking us? What risks are you talking about? The issue is simple. …Nothing will happen without our consent. The Russian authorities have long known our position. Our position is that any relations will be restored only when Russia recognises Georgia’s territorial integrity and the de-occupation of our territories takes place. …The Georgian authorities have no communication in this direction. As for restoring relations with the Russian Federation, there is a simple precondition — recognition of territorial integrity is the key point,” said Papuashvili.

To understand why the Russian deputy prime minister so unexpectedly made a public statement about plans to organise direct railway service with Georgia via Abkhazia, it is important to consider the context in which the remarks were made. Armenia’s railway infrastructure was transferred in February 2008 to concession management by the South Caucasus Railway, a subsidiary of Russian Railways, for a period of 30 years with the option of a 10-year extension. Until recently, this was seen as a guarantee that large-scale transit projects in Armenia would not be implemented without Russian participation. However, the situation changed after the signing in August 2025 of an agreement to establish the Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity (TRIPP) through Zangezur, which is expected to be developed without Russian involvement.

From that point onward, Moscow began frantically searching for its own “routes” to avoid being sidelined in the process of establishing peace and reopening transport links in the South Caucasus. In particular, Alexey Overchuk has been actively advocating for transit through Armenia between Azerbaijan and Türkiye — not via Zangezur, but along alternative routes using Armenia’s existing railway network, which remains under Russian concession.

Had Russia acted promptly to pursue a genuine peace settlement and truly reopen communications in the South Caucasus, a hypothetical “Putin Route” could already be operating in place of the “Trump Route” through Zangezur.

The “window of opportunity” for Moscow opened in November 2020 with the signing of the Trilateral Statement following the Second Karabakh War. Russia assumed the responsibility of ensuring the security of transit through Zangezur. Yet, for unclear reasons, the same South Caucasus Railway did not begin promptly restoring the railway through Meghri.

Instead, the Kremlin effectively spent time and resources supporting revanchist sentiments among Moscow-aligned politicians in Yerevan and the remnants of separatists in the Karabakh region of Azerbaijan. With Moscow’s consent, Russian-Armenian billionaire Ruben Vardanyan was sent to Karabakh, taking the post of so-called “state minister of the NKR.”

The outcome is well known: the separatist entity in Azerbaijani Karabakh was ultimately dismantled, and its officials, including Ruben Vardanyan, faced trial in Baku. Moscow, despite having the chance to become the main moderator of the process of reopening transport links, missed the strategic moment — a gap that was then seized by US President Donald Trump, who positioned himself as a peacemaker.

Nevertheless, Moscow appears to continue following the same logic regarding other separatist entities — in the occupied Georgian regions of Abkhazia and the Tskhinvali region. As a result, the existing “window of opportunity” to maintain influence in the South Caucasus under the new circumstances is rapidly narrowing.

Instead of taking advantage of the Georgian Dream administration’s apparent willingness to pragmatize relations with Moscow — by initiating the de-occupation of Georgian territories, ensuring the return of refugees, and moving toward genuinely unblocking communications — resources continue to be directed toward the institutional “consolidation” of the separatist regimes. In this effort, the deputy head of the Presidential Administration of Russia, Sergey Kiriyenko, has been appointed as the overseer of these initiatives.

Regarding the transit project through Armenia “bypassing” Zangezur, pro-Kremlin forces in Armenia—known for their anti-Georgian rhetoric—sought to shape it in a way that would minimise Georgia’s role. The pretext was the inflated tariffs previously imposed in Tbilisi on railway transit of oil products from Azerbaijan to Armenia.

Certain political circles in Yerevan took advantage of this, actively promoting the idea of transit between Azerbaijan and Türkiye that would bypass the “Trump Route” and exclude Georgia entirely. Notably, the possibility of transit through Abkhazia was not even discussed at the time.

However, Tbilisi quickly realised the necessity of facilitating transit between Azerbaijan and Armenia on preferential terms. Recently, Ilham Aliyev publicly thanked Georgia for creating important transit opportunities.

Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan also reacted negatively to Alexey Overchuk’s statements about Russia’s possible involvement in restoring Armenia’s border railways. Essentially, he diplomatically suggested that Russian railway entities leave Armenia, arguing that Russian management of the railways causes the country to lose strategic positions and competitive advantages.

Pashinyan proposed transferring the railway concession to a third country that has friendly relations with both Yerevan and Russia. He emphasised that the “Trump Route” through Zangezur is more attractive to international partners than routes using Armenia’s existing railway network, precisely because of the Russian factor.

“In my view, the solution would be for a country that has friendly relations with both Armenia and Russia to simply purchase from Moscow the right to manage the railway concession… I don’t know, for example, Kazakhstan, the UAE, Qatar, or some other country that doesn’t come to mind right now. But it should be a country that maintains equally strong relations with both Russia and Armenia,” said Nikol Pashinyan.

Moreover, according to Pashinyan, even if Russia were to invest the necessary funds to restore the border sections of the railway, this might not change the situation. The overall circumstances, he noted, are such that the route through Armenia would still not be used, precisely because the railways remain under Russian concession.

Thus, Moscow’s urgency to restore railway connections with the South Caucasus via Abkhazia becomes clear — in effect, it is one of the last tools available to slow Russia’s rapid displacement from the region. Otherwise, Russia could even be pushed out of Armenia’s railway sector entirely.

Only by establishing a direct and reliable link between its railways and the Georgian Railway through Abkhazia — and from there to the railway networks of Türkiye, Armenia, and Azerbaijan — can Russia hope to retain its status as a fully influential player in regional transport development and, potentially, in transit along the Middle Corridor.

Moscow could also propose an important “northern railway branch” to the Middle Corridor — via Abkhazia and the North Caucasus — and in the long term, if the war in Ukraine ends, potentially extending through Ukrainian territory to Europe.

This is of interest not only to Armenia. If the Rasht–Astara railway—which Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian recently promised to accelerate—is completed, combined with rail connections through Abkhazia, it could create the shortest and potentially most efficient “North–South” route, linking the Indian Ocean coast to Europe via Iran, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Russia.

However, without Georgia’s consent, the implementation of such projects is impossible. Unlike Russia, Tbilisi today can afford a wait-and-see approach. Georgia is already an important link in the Middle Corridor and is actively developing transit projects without Moscow’s participation. In the matter of possible transit through Abkhazia, it is precisely Georgia that sets the conditions.

Notably, the “window of opportunity” for Russia to fully integrate into new regional transit architectures will be open for only a limited time. A few more months, and the interested parties may find ways to finally unblock communications in the South Caucasus without Russia’s involvement. At the same time, Pashinyan’s government is capable of accelerating the process of sidelining its “ally,” including by reviewing or terminating the Russian Railways concession on Armenian railways. In that case, Moscow would be left relying only on formal “allied” structures to support separatist entities in the occupied Georgian territories, which continue to lose both population and economic potential.

Moscow should also understand that, regardless of the loyalty of the Georgian Dream administration to Russia, it is impossible to talk about railway or other transit through Abkhazia without the start of a real process of de-occupation of Abkhazia and the Tskhinvali region. In this matter, Georgian society demonstrates a consensus. Both supporters of the current government and the opposition advocate for de-occupation and the return of refugees. There are virtually no political forces in Georgia willing to relinquish the occupied territories or agree to “freeze” their status in exchange for opening transit through Abkhazia—even among those who traditionally sympathise with Russia.

That is why Tbilisi’s position is formulated very clearly: first de-occupation, then the restoration of railway connections.

Is Moscow ready to accommodate Tbilisi on the issue of recognising Georgia’s territorial integrity and reconsidering its “recognition” of the separatist entities? Until recently, Russian official statements emphasised the alleged impossibility of such a step, urging Georgia to “accept the realities.” However, the dynamics of regional processes are changing rapidly.

After the announcement of the “Trump Route,” it became clear that Russia needed railway connections through Abkhazia “yesterday.” Without this line, Russia’s influence in the South Caucasus could shrink to a symbolic level tomorrow. At the same time, organising such transit without Georgia’s consent is impossible.

Undoubtedly, Russian propaganda will have to explain “difficult decisions” to the public if it comes to withdrawing recognition of the so-called “independence” of the separatist entities in Georgia’s occupied territories. However, Moscow already has experience with such “difficult decisions” and “gestures of goodwill” in situations where strategic necessity demanded them.

It is enough to recall March 2022, when Russian forces were advancing on Kyiv and controlled significant portions of the Kyiv, Chernihiv, and Sumy regions in northern Ukraine. At the time, statements were made claiming that Russia had arrived “for good.” Yet, confronted with the risk of heavy losses due to overstretched supply lines, the Kremlin declared a “gesture of goodwill” and rapidly withdrew its troops from the northern front.

In September 2022, Moscow took another step—organising so-called “referendums” and subsequently incorporating Ukraine’s Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions into the Russian Constitution, even though the regional capital of Zaporizhzhia remained outside its control and no referendum was actually held there. Nevertheless, Kherson and the right-bank part of Kherson region were later lost, and Russian attempts to advance toward Zaporizhzhia continue without achieving any strategic gain.

The experience of recent years shows that revising previously made decisions—even those enshrined at the constitutional level—is not an absolute taboo for the Kremlin if the military-political context changes. In this light, withdrawing recognition of the so-called “independence” of Abkhazia and the so-called “South Ossetia” would no longer appear as an unprecedented move. Especially since, in theory, Tbilisi could propose formulas allowing Moscow to preserve certain economic interests in these territories while minimising reputational costs.

Formats of “soft de-occupation” could vary. Currently, Russia, with U.S. mediation, is negotiating with Ukraine on possible ways to freeze military actions and discussing mechanisms for the economic functioning of certain territories while their de jure status remains part of Ukraine. Similarly, options for special economic regimes could be considered for Georgian Abkhazia—taking into account Russian economic interests—while returning the region under Georgian jurisdiction and ensuring the right of refugees to return.

By Vladimir Tskhvediani, Georgia, exclusively for Caliber.Az