Moldova’s path and Georgia’s choice European integration vs. national sovereignty

In Tbilisi and Chișinău, authorities take markedly different approaches to the question of whether European integration is worth the potential loss of statehood. While Georgia, without formally abandoning its European path, has opted to strengthen its statehood and national sovereignty, in Moldova there are high-level discussions today about the very real possibility of dissolving the state and uniting with ethnically close Romania.

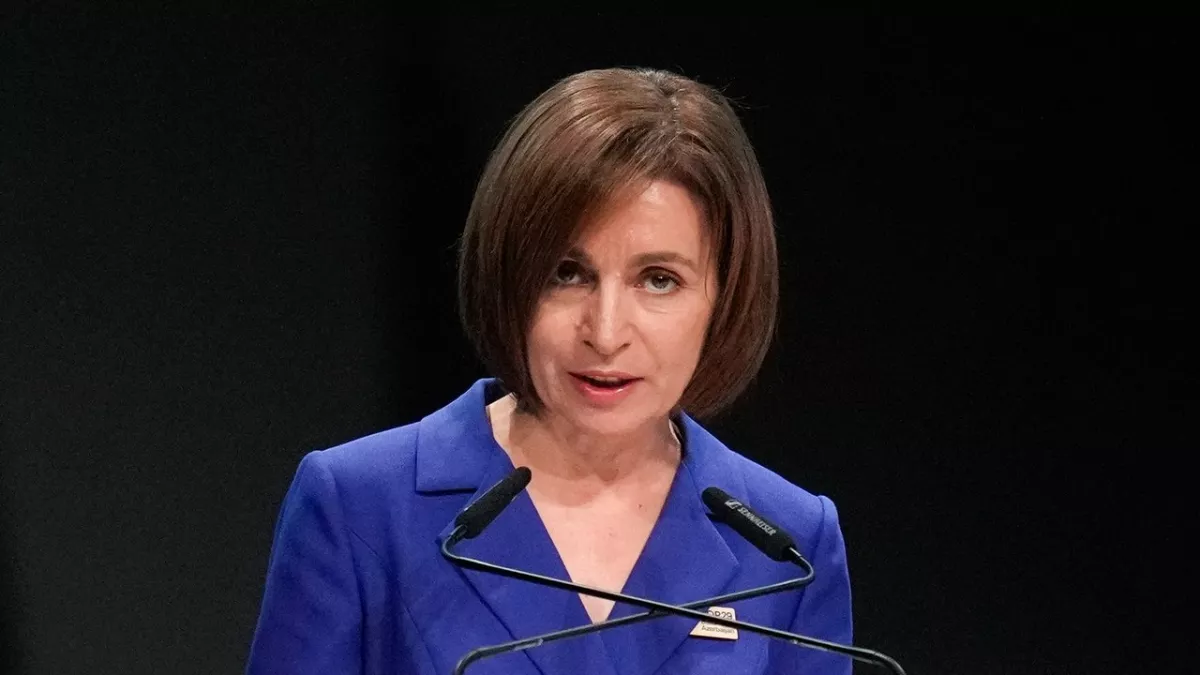

Moldovan President Maia Sandu stated in the popular British YouTube podcast The Rest Is Politics that, in the event of a referendum on her country joining Romania, she would vote “in favour.”

“Look at what's happening around Moldova today. Look at what's happening in the world. It is getting more and more difficult for a small country like Moldova to survive as a democracy, as a sovereign country, and, of course, to resist Russia,” Maia Sandu said.

Meanwhile, she acknowledged the absence of a domestic consensus on the issue, noting that a majority of Moldovan citizens do not currently support reunification with Romania. “[...] there is not a majority of people today who would support the unification of Moldova with Romania. But there is a majority of people who support EU integration, and this is what we are pursuing, because this is a more realistic objective,” she said.

Her remarks triggered a wide-ranging debate over the future of Moldovan statehood, both within the Republic of Moldova and internationally. The statement also drew reactions from Georgian officials.

Georgian Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze openly expressed surprise at the Moldovan leader’s intention to vote for the loss of her country’s independence: “This statement is astonishing for me. A political leader declares that she is ready to vote for the loss of her country’s independence. When a political leader makes such a statement, I don’t even know what comment to make. This is a very regrettable development for Moldova, a country that gained independence together with us in the early 1990s. The rest is Moldova’s matter; they will probably sort out their own issues themselves.”

The Speaker of the Georgian Parliament, Shalva Papuashvili, also sharply criticised the statement by Maia Sandu. He argued that the scenario of losing independence outlined by the Moldovan president is intended to accelerate the country’s European integration. For Georgia, however, such a path is completely unacceptable: “When a country’s president intends to vote against the country’s independence, everything is clear. In this respect, yes, we are behind Moldova. What can we do? We are not giving up our three thousand years, which is proof that if you believe in your national identity, then even a ‘small country’ can establish its own statehood in the historical turmoil.

At the same time, this statement indicates that the President of Moldova is sceptical about the country’s prospects of integration into the EU independently and considers the German Democratic Republic scenario, the way which brought the GDR into the European Union on the very day it joined the Federal Republic of Germany. What can be said? This is also a way to Europe by losing sovereignty. I am confident that our nurtured ‘hyper-Europeans’ might be looking to these two countries, and by citing Article 78 of the Constitution, would cede Georgia’s sovereignty immediately. For them, no article is worth an article before Article 78. For us, the issue is simple – Georgia’s European path is the path of an independent state, not its abolition.”

At the same time, it should be noted that Maia Sandu, in her statement about Moldova joining Romania, was expressing the actual sentiments of a certain segment of her electorate—primarily those citizens who, in addition to holding a Moldovan passport, also already possess Romanian citizenship.

Pro-integration sentiments favouring full unification with Romania do exist within Moldovan society. While Georgia and Moldova share many cultural and historical ties, the trajectory of Moldovan statehood and the development of its national identity have unique features that set it apart from the Georgian experience.

Both Georgia and Moldova are Orthodox countries that, at different points in history, were part of the Russian Empire and later the Soviet Union. Earlier still, both Moldova (then the larger Principality of Moldova, not the current Republic) and the Georgian polities were under the dominion of powerful Muslim empires—most notably the Ottoman Empire—while retaining a degree of internal autonomy.

In the 16th–18th centuries, the western Georgian polities—Imereti, Guria, Mingrelia, and Abkhazia—were vassals of the Ottoman Empire, just as the principalities of Wallachia and Moldova were. Today, Wallachia and the western lands of the historical principality of Moldova belong to modern Romania, while the present-day Republic of Moldova occupies the eastern portion of that principality.

An unsuccessful war with Russia weakened the Ottoman Empire and effectively led to the partition of the Principality of Moldova in 1812. Its eastern territory—between the Prut and Dniester rivers, known as Bessarabia—was annexed by the Russian Empire. The remaining western part of the principality continued to maintain autonomy under Ottoman suzerainty. In 1859, it united with another Ottoman autonomous territory, Wallachia, forming a single principality. In 1877, at the outbreak of another Russo-Turkish War, it declared independence and became known as Romania, while Bessarabia remained a province of the Russian Empire.

Thus, the policies of the Russian Empire in the 19th century contributed to the divergence of the historical paths of the populations of present-day Romania and Moldova. At the same time, the empire consolidated the territories of what is now Georgia within its borders, a development that played a key role in the restoration of Georgian statehood in 1918. However, this period was short-lived: by 1921, the country was occupied by the Red Army, and the Georgian SSR was established.

Following World War I and the collapse of the Russian Empire, Bessarabia came under Romanian control for a time. The Soviet Union never recognised this, viewing Bessarabia as “occupied territory.” Meanwhile, on the left bank of the Dniester, within Soviet territory, the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (Moldavian ASSR) was established as part of the Ukrainian SSR — much of this territory now corresponds to the breakaway region of Transnistria.

In 1940, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) annexed Bessarabia, and its main portion, together with most of the Moldavian ASSR, was merged into the Moldavian SSR.

As a result, the present-day Republic of Moldova, as the successor of the Moldavian SSR, emerged through a series of complex and repeated territorial rearrangements. At the time of the USSR’s collapse, Georgia’s national idea centred on building an independent state. In contrast, in Moldova, a significant segment of the national intelligentsia placed its hopes on the notion of “reunification” with ethnically and culturally close Romania.

The idea of “reunification with Romania” was, in turn, exploited by Soviet intelligence agencies to foment the Transnistrian separatist movement, initially aimed primarily at resisting the prospect of “Romanisation.” In the early 1990s, Romania was not an EU member, as it is today, but one of Europe’s poorest countries, grappling with serious socio-economic challenges. Consequently, the prospect of becoming part of Romania did not appeal to most Moldovan citizens.

During its time within the Russian Empire and the USSR, Moldova developed its own cultural environment, not entirely identical to that of Romania, and fostered a distinct literary tradition. This process was further shaped by the fact that, during the Soviet period, the Moldovan language (as Romanian was officially called in the Moldavian SSR) was written in Cyrillic—a script that continues to be used for the language in Transnistria to this day.

Living alongside Russians and Ukrainians within a single state has brought the citizens of Moldova culturally and psychologically closer to the East Slavic peoples than to Romanians. Moreover, in the south of the Republic of Moldova resides a sizable Turkic-speaking minority—the Gagauz—who enjoy their own autonomous region, Gagauzia. The Gagauz reasonably fear that preserving their culture and identity within a larger national state would be far more challenging than within present-day Moldova, and that they could face accelerated assimilation.

The aspiration for Moldova’s unification with Romania might be more understandable if Romania were a major centre of power within the European Union, wielding influence comparable to that of Germany or France, and if it not only maintained its own national identity but also projected cultural influence across Europe. However, this is not currently the case—and there is little prospect of it happening in the foreseeable future.

In terms of political weight and economic potential, Romania still belongs to the “second tier” of European states and generally follows the course set by Brussels. At the same time, Hungary—which is noticeably smaller than Romania in both territory and population—pursues a more independent economic policy and consistently defends its national characteristics and identity.

Recently, Romania has also drawn attention for disregarding democratic procedures and the will of voters in favour of political expectations from Brussels. In December 2024, the winner of the first round of the presidential elections—a right-conservative candidate, Călin Georgescu, who did not align with the European bureaucracy or Romanian liberals—was effectively denied victory: the results of the first round were annulled, and he was prohibited from running again. This decision by Romania’s Constitutional Court was fully supported at the time by Maia Sandu, but it sparked sharp discontent both within Romania and in neighbouring Moldova.

Today, far from all Moldovan citizens share Maia Sandu’s views. Many, even those who identify as Romanian, are unwilling to give up a sovereign state even for the sake of accelerated European integration. Such sentiments are even more absent in Georgia—especially among those who understand the historical depth and uniqueness of Georgian statehood.

By Vladimir Tskhvediani, Georgia, exclusively for Caliber.Az