Bollywood with nuclear missiles How India’s ambitions are fuelling regional chaos

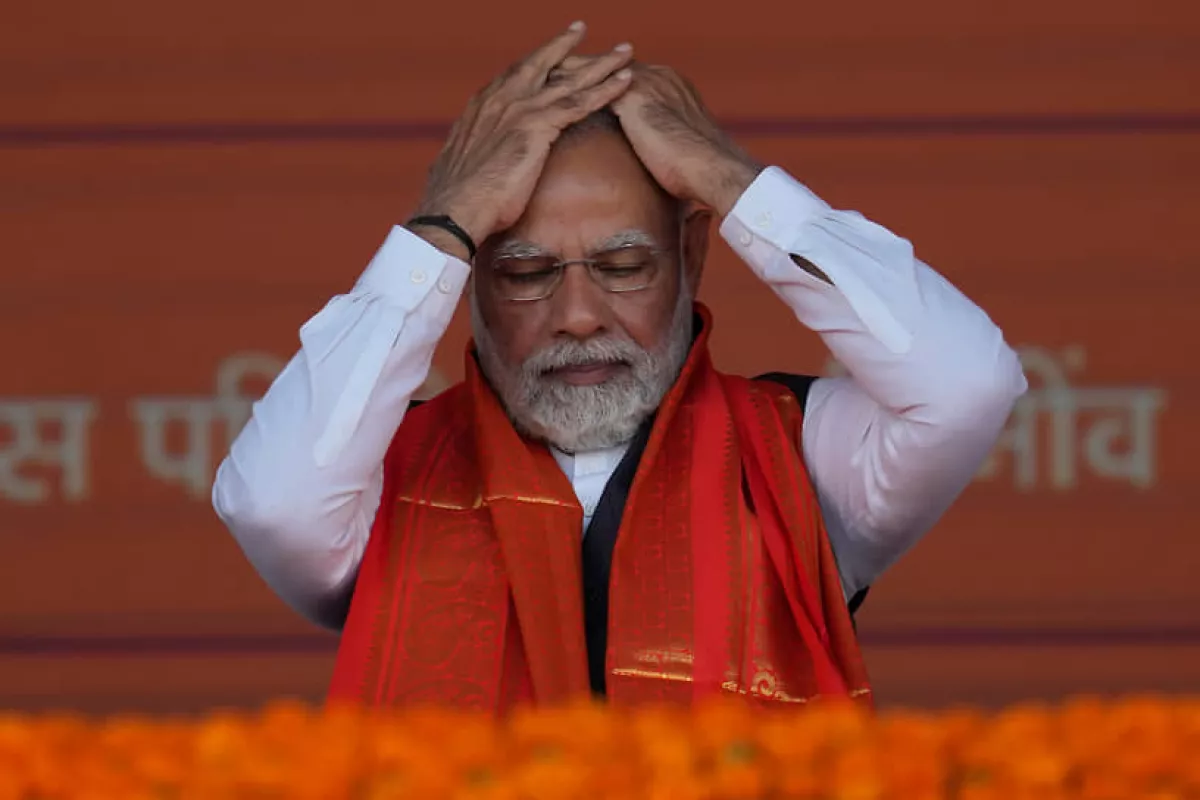

This week, the Prime Minister of India made his own contribution to the escalation of a potential world war. Narendra Modi threatened neighbouring Pakistan with “destruction.” Although this statement followed an Indian attack on Pakistan, the international community chose to ignore it. By allowing Modi to trample on international law, the collective West is trying to halt India's cooperation with Russia and pit it against China.

In turn, the Indian government is exploiting global powers' interest in partnering with Delhi, and its ambitions are growing. Among other things, the Indian authorities also support Armenian revanchism. However, as we watch Delhi's attempts to play the role of a “superpower,” it is worth remembering that India’s vast size has so far only translated into colossal failures in development and the realisation of its outsized ambitions.

Bloody yoga or perfect conditions for extremism

Last week, the world was focused on the risk of a clash between Asia’s two largest nuclear-armed states — India (with a population of 1.4 billion) and Pakistan (248 million). Following the April 22 terrorist attack in Kashmir, Delhi opted for a “small victorious war.” The Indian leadership accused Pakistan of orchestrating terrorist activities and launched an attack on its neighbour on May 7. However, dealing with the Pakistani army proved to be no easy task, and Delhi rushed to de-escalate the confrontation just four days later, on Sunday.

There are important nuances in the actions and rhetoric of the Indian leadership that deserve closer attention, as they clearly illustrate what is fundamentally wrong with modern global politics. For starters, the accusations against Islamabad paint a cartoonish picture — as if the all-powerful Pakistani intelligence services are disturbing the peace of a tranquil India. But there is no “peaceful India,” nor peace for its citizens — especially those who do not adhere to the radical version of Hinduism promoted by the ruling party. The situation is even worse for Muslims and Sikhs.

Among the clearest examples of mass discrimination against India’s Muslim citizens of various ethnic backgrounds is the situation in Kashmir, located at the intersection of the Indian, Pakistani, and Chinese borders. Kashmir’s status remained unresolved following British colonisation. As they withdrew from the subcontinent, British leaders — most notably Winston Churchill — turned the region into a perpetually bleeding wound. They created two states on the Indian subcontinent based on religious identity, yet failed to give the populations of certain areas the right to choose which country to join. Kashmir, with its Muslim-majority population, was one such territory.

Problems erupted almost immediately in the late 1940s. In response to social and economic marginalisation, discrimination, and repression by the Indian government, radical movements began to grow in Jammu and Kashmir — the most troubled Indian state. The logical response would have been to invest in regional development and pursue an inclusive, participatory resolution of its status. But that never happened. Over the past 15 years, India has actively moved away from secularism, evolving into a state increasingly defined by Hindu nationalism — a dangerous path, given the large number of non-Hindu citizens (Muslims alone number 230 million).

At the forefront of this transformation stands Narendra Modi and his nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). After coming to power in Delhi in 2014, they immediately began promoting a concept of ethnic Indian nationalism known as Hindutva. Narratives about the glorious ancient culture of Hinduism — many of them based more on the imagination of ideologues than on historical fact — have served as a smokescreen for the destruction of real, ancient non-Hindu cultures in the region, such as Sikh and Muslim heritage.

Just this year, two mosques and a madrasa were demolished in India under the pretext of “illegal construction” — even though they had stood since the late medieval period. Modi’s vegetarianism and affinity for yoga, shared by many of his allies, have not prevented the regime from turning a blind eye to the killings of non-Hindus. No sooner had Modi assumed leadership of the Indian state of Gujarat than, under his watch, a brutal pogrom against local Muslims took place. In 2002, Hindu mobs rampaged through one of the state capital’s districts for nearly ten hours, murdering and raping people of other faiths. The death toll reached 97 — a figure too high even by Indian standards. And yet, this did not hinder Modi’s political rise.

In the years that followed, Modi acted more cautiously, but he continued transforming the country into an Aryan Hindu state. The liberal Western establishment may have wrinkled its nose, but it offered little resistance — largely because Modi pursued a pro-Western, anti-China policy, opened India’s markets and resources to the West, and adhered to a neoliberal economic agenda. As a result, he was given a free hand — including in dealing with rebellious Kashmir, which Modi resolved to crush outright.

It was under his leadership in 2019 that the Indian government, citing “terrorist activity,” abolished the state of Jammu and Kashmir altogether. Notably, this was no ordinary administrative region of the Republic of India — it held a constitutionally enshrined, though long-dormant, special status due to its unique historical circumstances. Modi trampled the constitution and broke the state into two disenfranchised “union territories”: Jammu and Kashmir, and Ladakh.

While unequivocally condemning terrorist attacks against civilians, it must be stressed that such acts cannot serve as justification for repression against Kashmiris and other Muslims. The conditions for such attacks have been created by the actions of the Indian authorities themselves — it is they who, for years, have fostered the environment for radicalisation and the emergence of extremist violence.

The relentless discrimination and repression targeting Kashmiris have been accompanied by the chronic dysfunction of the Indian state — a disorder that has plagued the country since its very founding. These are ideal conditions for terrorism to take root. And as history shows, in such dysfunctional states, security services often go beyond merely enabling the conditions for radicalism — they infiltrate extremist groups with dangerous provocateurs. From the time of the 1905 Russian Revolution, ignited by police agent Father Gapon, little has changed in this regard.

Not righteous anger, but a sales pitch

What deserves attention here is not merely the strained attempt to blame Pakistan for every failure of India’s policy of suppressing Kashmiri dissent. Similar terrorist attacks have occurred in the past. Yes, 26 civilians were killed — a tragic loss — but this was far from the first such incident, and previous events of this nature did not trigger such an outsized response. So what’s different this time?

The explanation should not be reduced to the personality of the Indian Prime Minister — Modi knows how to switch his outrage on and off as politically expedient. Instead, the focus should be on the current geopolitical configuration. The escalation took place against the backdrop of intensifying U.S.–China rivalry, and Pakistan — regardless of its changing governments — has always been China’s closest ally.

Modi is clearly eager to demonstrate India’s military utility to the United States in order to negotiate more favourable terms from Donald Trump, who has also demanded that India provide preferential treatment to American companies.

In effect, Modi has announced a policy of heightened confrontation with Pakistan — a move that, it bears repeating, is tantamount to a policy of confrontation with China. For Beijing, everything related to Pakistan is viewed as part of its own strategic interests. It is worth recalling that even when Pakistan waged a full-scale covert war against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan, it initially did so at the urging — and with the backing — of China.

Modi is clearly attempting to craft a political course that would force Beijing to remain perpetually preoccupied with the India–Pakistan confrontation — a scenario Washington would undoubtedly welcome. To this end, he has declared an intention to make tensions permanent, announcing a downgrading of ties with Pakistan and proclaiming: “If there are talks with Pakistan, it will be only on terrorism; and if there are talks with Pakistan, it will be only on Pakistan-occupied Kashmir.”

What’s notable is how several mainstream Western media outlets — along with their pro-Western counterparts elsewhere — have simply echoed these blunt demands, without explaining to their audiences that the latter point effectively amounts to India demanding that Pakistan accept its territorial expansion in Kashmir. This reaction is hardly surprising. The Western establishment views the situation as an opportunity to trouble China, particularly as Indian expansionism in Kashmir also carries implicit claims against Chinese-controlled territory.

As for the first demand — negotiations focused solely on terrorism — it practically guarantees a long-term, manageable, yet easily inflamed confrontation. India’s leadership understands this well, since the demand is inherently unfulfillable. Radical groups in Kashmir and other regions of India are, above all, products of local conditions. To portray them as mere proxies of Pakistani or other foreign intelligence services is simplistic at best — and Islamabad, in any case, cannot simply order them to stand down.

An unfulfilled global power

However, when discussing the destructive actions and threats directed at Pakistan by India’s leadership, it would be mistaken to reduce everything to the figure of the Indian Prime Minister or his party. The main opposition force, the Indian National Congress, not only fully supported the strike against Pakistan but also later criticised the government for its “premature” halt of the offensive and for refraining from launching a broader military campaign. Echoing these sentiments are influential public figures — Indian social media personalities who are now demanding an even tougher stance towards the neighbouring country.

Toxic Indian nationalism, formalised under the doctrine of Hindutva, has seen significant expansion over recent decades. By invoking the myth of a mighty, ancient “eternal India,” the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is essentially advancing an ideology rooted in racist theories imported from Anglo-Saxon countries during British colonial rule. This foreign origin partly explains the paradox of glorifying an “Aryan civilisation” in a country where a substantial portion of the population is non-Aryan — particularly Dravidian.

Moreover, much of what is now portrayed as the bedrock of Hindu societal identity is, in fact, the result of colonial-era cultural engineering. In their efforts to dominate the vast and historically cohesive Indian subcontinent, the British deliberately dismantled existing socio-political structures. These traditional structures had long integrated Hindus and Muslims, and the governance of major Indian polities had, by that time, become inseparable from Muslim participation.

The British embarked on a project to “excavate” what they claimed was a pure, ancient Indian culture — one supposedly tainted by centuries of Muslim influence. The myths surrounding Sanskrit, the caste system, and similar constructs were, in large part, the products of British colonial institutions. These institutions pieced together fragments — often anachronistic — of India’s social realities to fabricate a version of Indian culture that served imperial interests.

This manufactured cultural framework also allowed the racist Anglo-Saxon elite to trace the ideological ancestry of their supremacist fantasies not to the barbaric medieval Germanic tribes of Northern Europe, but to the supposedly glorious “ancient India.” By invoking a shared Aryan or Indo-European heritage, they sought to legitimise their colonial and racial ideologies. Even Hitler borrowed heavily from these British-imposed racial constructs — he didn’t invent them but repackaged the colonial nonsense developed by the British in South Asia. Crucially, these constructs were never truly dismantled in India, and many of them persist in national discourse to this day.

The British, of course, ruled the subcontinent — from modern-day Myanmar and Bangladesh to India and Pakistan — until World War II. And they likely would have continued their dominion, had the Japanese not fractured the British imperial system in Asia, reaching the doorstep of modern India within a few years. When the British eventually withdrew, they left behind a fractured region, deliberately partitioned into vulnerable states. The creation of Pakistan itself was a product of this imperial exit strategy — split into two non-contiguous regions, separated by hundreds of kilometres of Indian territory. It was only in 1971, after a brutal conflict, that East Pakistan broke away to become the independent nation of Bangladesh.

The ideology of the Indian state, built on dubious historical myths, has prevented it from establishing normal relations with its neighbors, primarily its largest neighbor — Pakistan. Although India fought wars with China and engaged in destructive but ultimately futile interventions in the politics of other neighbors, especially Afghanistan and Sri Lanka, the outcome was that one of the world’s largest countries — which at the dawn of independence in 1947 was predicted to become one of the leading powers among developing nations — remained a poor, underdeveloped country with a barely functioning state system.

By comparison, China and India were roughly at the same level of development in the late 1940s, but the question of how vast the gap between them is today is rhetorical, as the gap is not just multiple times over — it spans entire historical epochs and technological eras. The Indian elite lost its chance by fostering hostility with its neighbors, especially Pakistan.

By the way, even this is becoming increasingly difficult for India — a clear example is one of Narendra Modi’s previous attempts to attack Pakistan. In 2019, just like now, he accused Pakistan of supporting radical groups and sent the Indian army to bomb a “terrorist camp,” announcing the elimination of numerous militants. The next day, however, Pakistan shot down an Indian fighter jet and captured its pilot, while the Indians ended up destroying their own helicopter with crew and passengers on board — though they kept quiet about this for several months. Moreover, shortly after the attack, foreign journalists reported that they found no evidence of any damage from the bombing, neither from satellite images nor on the ground. If such things happen in the army, one can only imagine how less regulated state institutions in India function.

In political analysis, there is a well-known term “failed state,” which is applied to countries with dysfunctional government systems and anarchic societies lacking any prospects for socio-economic development or stable public institutions. In this vein, India is increasingly better described as a “failed global power.” It can bomb Pakistan and provoke China in an attempt to demonstrate its value to the global hegemon, it can boast about past greatness, and even try to destabilize the South Caucasus. All this only further highlights the bankruptcy of India’s state project, as it is genuinely difficult to imagine more senseless actions to lift the country. Sadly, this does not diminish the danger posed by the destructive consequences of such policies.