Dangerous Iranian September Rising domestic and regional pressures

Iran is facing serious diplomatic pressure and is under the threat of new Israeli strikes, while its economy is going through a difficult period.

Diplomatic crisis

Tehran risks sliding back into multilateral isolation by the end of September, as the deadline for the reinstatement of UN sanctions is rapidly approaching. The “European trio” (France, Germany, and the United Kingdom) has started a thirty-day countdown to the reimposition of UN sanctions against Iran.

Russia and China have expressed disagreement with Europe’s actions, offering diplomatic support to Tehran. It remains unclear, however, how far they are willing to go if matters come to a head. The point is that the adopted sanctions mechanism does not allow the permanent members of the UN Security Council to veto it.

These sanctions will cost Iran billions of dollars, and its trade relations with Europe will be destroyed. For an economy already in crisis, this decision will represent another serious blow.

Preparation for a new Israeli attack

The twelve-day war in June 2025 demonstrated the effectiveness of precision strikes. Israeli attacks killed senior IRGC (Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps) commanders, damaged bases housing drones and missiles, as well as defence factories, decision-making centres, and television facilities. U.S. forces joined the Israeli Air Force, carrying out limited but significant strikes on selected nuclear sites, temporarily disrupting the uranium enrichment process.

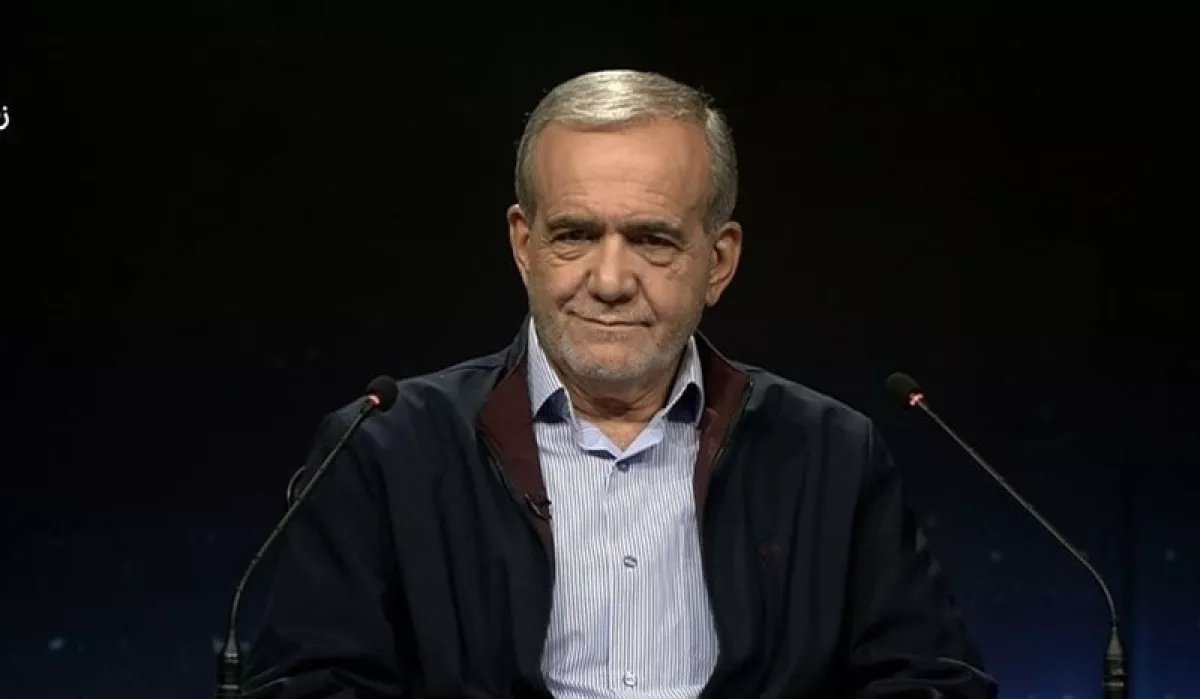

Iran may be able to rebuild its nuclear industry, but this episode exposed the vulnerability of its most critical assets. President Masoud Pezeshkian openly expressed doubts about the feasibility of restoring nuclear facilities. In response to remarks from conservative supporters of the Supreme Leader, he said: “If we rebuild the nuclear facilities, they are going to attack them again. What can we do if we do not enter negotiations?”

This continues the logic of the reformist factions within the Iranian regime, to which Pezeshkian belongs, advocating for détente between Iran and its opponents. Reformists have consistently questioned the point of Iran’s attempts to develop nuclear weapons. In the end, nuclear weapons were never created, the nuclear facilities that received huge investments were destroyed, and the country lost billions of dollars due to sanctions.

The main outcome of the war is that Israel, by dismantling Iran’s air defence system—at least over part of its territory—gained air superiority over Iranian skies. This in itself encourages further strikes. Based on statements from Israeli politicians and military officials, the country’s Air Force is likely to launch a campaign aimed at undermining Tehran’s ability to control Iranian territory. They may continue targeted killings of Iran’s military and political elite, destroy nuclear and defence facilities, and strike energy and transportation infrastructure.

Israel has several reasons to resume attacks. First, simply because it can. It intends to control Iranian airspace to weaken the regime of its main Middle Eastern adversary. Here, the experience of Israel’s long-term military campaign against Syria—the “War Between Wars”—is instructive, which ultimately weakened Bashar al-Assad’s regime enough to facilitate its collapse under opposition attacks. In theory, a similar scenario could be possible in Iran, where opposition sentiments are strong.

Second, the window of opportunity will eventually close as Iran rebuilds its air defence capabilities, so Israel intends to accelerate military operations.

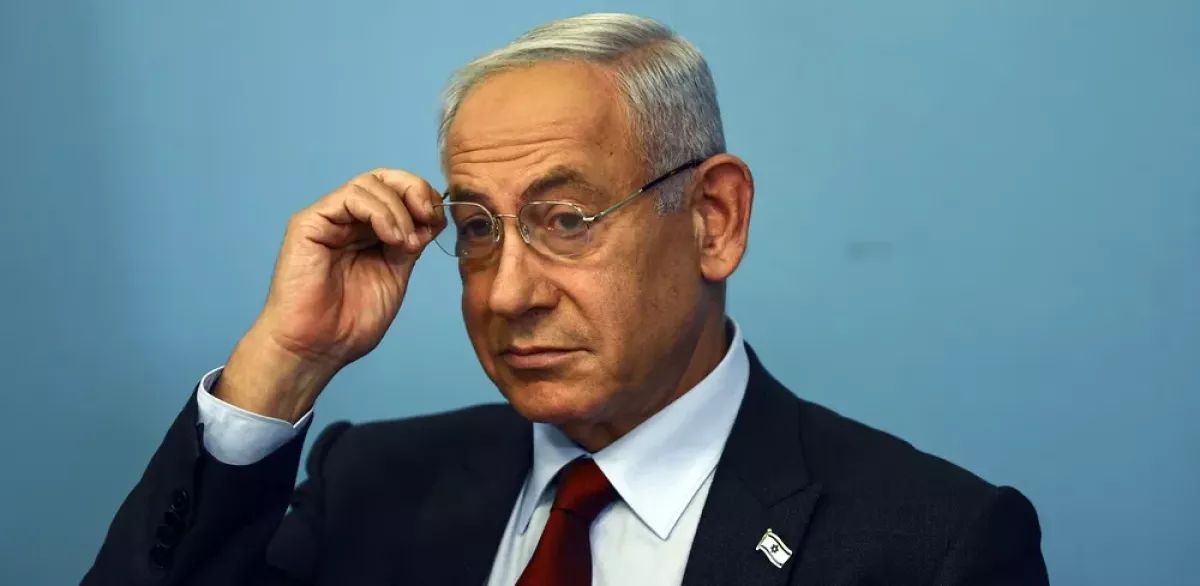

Third, the strikes on Iran have boosted the approval rating of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, meaning they may also be seen as politically advantageous for the country’s ruling circles for domestic reasons.

From its side, the United States— which tried after the twelve-day war to negotiate with Iran a halt to uranium enrichment—was disappointed. Iran refused to accept its main condition: “zero enrichment in exchange for sanctions relief.” If Donald Trump takes no action, it would appear as a clear political victory for Tehran over the U.S. president. Therefore, there is a strong likelihood that Trump will give Israel a “green light” to carry out new attacks against Iran. Most likely, the U.S. will participate only passively, defending Israel from Iranian missile counterstrikes. However, uncertainty remains regarding possible Iranian responses.

How will Iran respond to the strikes?

The twelve-day war highlighted the resilience of the Islamic Republic and its willingness to take risks. Tehran launched hundreds of rockets and drones at Israel. Although it achieved limited success (most rockets and nearly all drones were intercepted), around 30 civilians were killed, more than a thousand were injured, hundreds of buildings in Israeli cities were damaged, and one of Israel’s two oil refineries was temporarily knocked out. Iran will likely attempt to repeat such attacks if Israeli strikes resume.

Equally important is the global economic dimension. Iran has long threatened to close the Strait of Hormuz in the event of attacks, which remains the world’s most vulnerable energy chokepoint. About 20 per cent of global oil exports and a significant portion of liquefied gas pass through this narrow strait. Even limited military action in the area could trigger sharp rises in oil prices and create tension in economies from Europe to Asia.

If Iran responds in the Strait of Hormuz, the United States will most likely intervene to prevent Iran from striking tankers, sharply escalating the scale of the conflict. However, Iranian threats concern Trump, and so far, he has been restraining new Israeli strikes on Iran.

Rising domestic tensions

The summer has seen widespread power outages, water shortages, and a currency collapse, driving the Iranian rial to a historic low. Inflation has undermined living standards, fuelling public discontent. The reinstatement of UN sanctions could exacerbate instability, further limiting Tehran’s ability to procure essential goods from abroad.

The economy and infrastructure are in a critical state, and when entire cities are left without electricity and water for extended periods, it shocks the population. Protests are spreading across the country under the slogan: “Life, water, electricity!”

At the same time, strikes are taking place across industry and municipal services. Workers at petrochemical and metallurgical plants, transport workers, medical staff, and municipal employees are all participating. Normally, strikers demand to be moved from temporary contracts to permanent employment and to receive higher wages. Recently, however, there has been a rise in strikes demanding overdue salary payments, with delays ranging from two to five months.

These are deeply troubling trends: hungry or at least undernourished people, who are also cut off from electricity and water and deprived of basic services, may feel they have nothing left to lose. Moreover, due to the de facto ban on trade unions, some Iranian workers are organising strikes independently, without the support of cautious, regime-loyal legal union managers and lawyers.

Strikes organised by such illegal, clandestine workers’ groups and supported by their assemblies are usually more determined and uncompromising. In the 1970s, under the Shah’s regime, the number of illegal strikes grew by 20–30 per year, and the accumulated experience eventually led to a nationwide strike in the autumn of 1978, paralysing the economy. Some factories were even seized by workers and run independently. These events were among the key factors leading to the fall of the Shah’s regime.

Is there any indication that Iran is now experiencing the initial phase of the same process?

In any case, it can be said that today Iran is home to the largest strike movement on the planet. This is not an exaggeration: the modern working class rarely mobilises for strikes on such a scale.

Lake Urmia has ceased to exist

Iran’s military, diplomatic, and economic problems are compounded by an ecological crisis. Its causes are not only natural droughts but also policy decisions.

In an attempt to build a sanctions-proof, self-sufficient economy, Iran increased the production of rice and other water-intensive crops—previously, much of these had been imported. This led to a surge in the use of the country’s already very limited water resources. Combined with corruption and the incompetence of decision-makers, this policy triggered an ecological crisis, turning parts of Iran into a desert.

Satellite images from NASA obtained in recent weeks indicate that Lake Urmia—the largest lake in the Middle East, located in the northwest of the country—has ceased to exist.

The Iranian publication Ettelaat notes that the lake’s destruction had long been anticipated and predicted by experts. Over the years, Urmia gradually shrank until it disappeared entirely, leaving behind a vast salt-covered plain. But the region’s disasters are only beginning.

Soil salinisation is causing salt storms, which are devastating for agriculture. Around 13 million people living in the regions surrounding the former lake—mostly Azerbaijanis and Kurds—are at risk. This may create tensions between these communities and the central government.

Regime’s resilience

Numerous alarming signs point to growing problems for the Iranian regime. Yet it has repeatedly demonstrated its resilience. Neither the multi-million protests during the 2009 “Green Movement,” nor the uprising in November 2019, nor the large-scale demonstrations by youth and women in 2022–2023 succeeded in toppling it.

Israeli strikes have damaged or even destroyed some defence systems. Nevertheless, the country’s leadership has learned to live on the edge of a volcano. Iranian security forces have created a multilayered and largely decentralised network of various groups to suppress protests. This system relies not only on the police but also on the Basij—armed militias recruited from rural populations, willing to defend the government for high pay—as well as other types of militias formed from local security personnel, often granted virtually unrestricted authority to use violence.