From Georgia to Pakistan and Afghanistan: Who is the architect of chaos? Article by Vladimir Tskhvediani

On October 9, 2025, relations between Pakistan and Afghanistan sharply deteriorated, leading to armed clashes that reached a peak on October 11, 2025. Among the reasons cited for the escalation is the de facto (though officially denied) support by the ruling Taliban movement in Afghanistan for a Pakistani movement operating in border areas, which is attempting to overthrow the government in Pakistan by force.

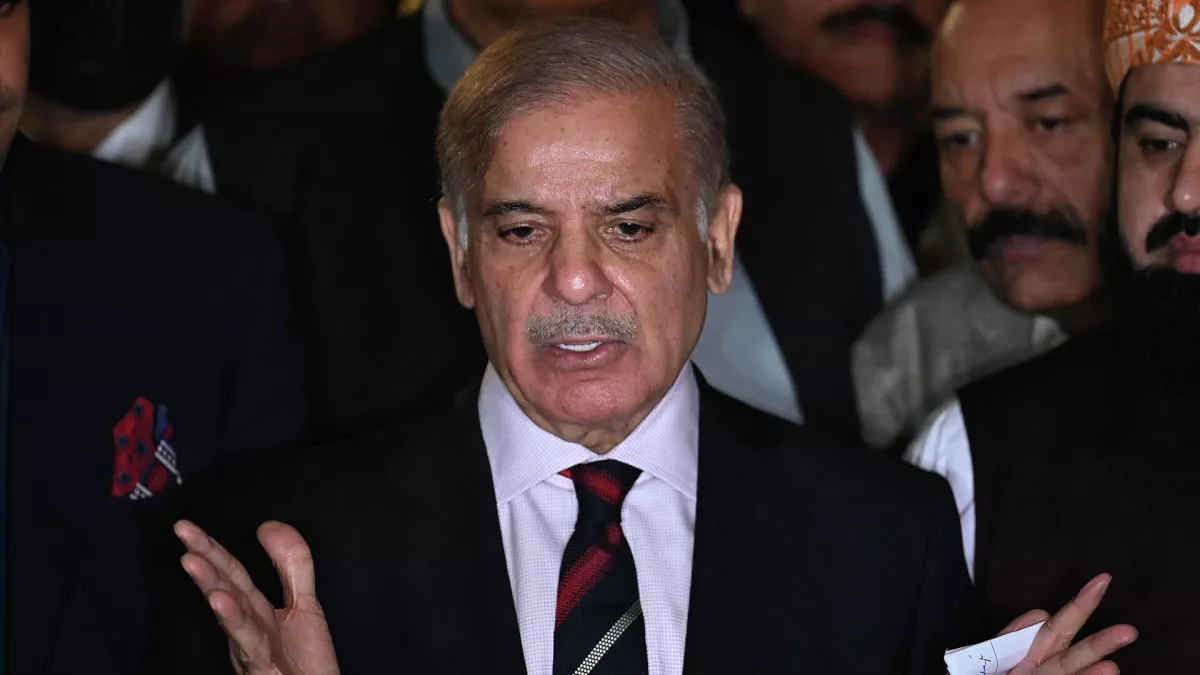

Pakistan’s Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif, in his address, highlighted the threat posed by terrorist groups operating from Afghan territory and called on the Taliban government not to allow Afghan territory to be used for attacks on Pakistan.

“There will be no compromise on Pakistan’s defense, and every provocation will be met with a decisive and robust response,” emphasised Shehbaz Sharif.

“Afghanistan is playing a game of fire and blood, the threads of which are woven with our eternal enemy. The people of Pakistan stand like an iron wall alongside the brave armed forces,” stated Pakistan’s Ministry of Interior on social media platform X.

On the night of October 11–12, 2025, the Afghan authorities backed down, and the country’s Ministry of Defence officially announced the cessation of clashes with Pakistan. However, tensions between the two nations remain high.

At first glance, there appears to be no connection between the latest attempted “revolution” and coup d’état in Georgia on October 4, 2025 and the recent armed clashes on the Afghan-Pakistani border. Yet it is evident that, had the coup in Georgia succeeded, it would almost certainly have been followed by the country’s involvement in a new war with Russia.

In turn, the opening of a so-called “second front” of the Ukrainian war in this region would have resulted in the disruption of transit along the Middle Corridor. Thus, instability in Georgia could have dealt a serious blow to the economic interests of several states.

Georgian President Mikheil Kavelashvili has accused the so-called “deep state” and the “Global War Party” of attempting to destabilise the country — and, consequently, of seeking to “block” the Middle Corridor. Many political analysts today use these terms to refer to liberal-globalist forces that reject the sovereign and independent policies of individual states, imposing instead a liberal agenda that ranges from LGBT advocacy to the abandonment of autonomous economic policymaking.

“I am confident that the majority of Georgian citizens agree with what we stand for: we are an independent and sovereign state striving to grow stronger. Unfortunately, there is another reality. There are forces that we call by various names — the ‘deep state,’ the ‘Global War Party.’ These forces view our country as a project — the ‘Georgia Project’ — bound by specific obligations in their global processes. They believe that Georgia’s role should be different. There are individuals who act as instruments of this project, receive instructions, and act accordingly,” said Mikheil Kavelashvili, commenting on the failed coup attempt.

Pakistan, of course, is much larger than Georgia and has considerably greater potential to pursue an independent policy. However, the external forces — essentially the same ones that view Georgia as a “project” serving purely utilitarian geopolitical aims (with “self-destruction” in a war against Russia being one such aim) — take a largely similar approach toward Pakistan.

According to their design, Pakistan is meant to destroy its own economic and demographic potential by becoming entangled in wars and conflicts that serve foreign interests, while abandoning a sovereign policy rooted in the needs of its own people. These forces disapprove of Pakistan’s cooperation with China — including within Eurasian transit projects. They also oppose Pakistan’s growing partnership with Türkiye and Azerbaijan. And, judging by the situation, the deep state seems indifferent as to who strikes at Pakistan’s sovereignty — even if it is the Taliban, a movement known for its “anti-Western” rhetoric.

Interestingly, on the eve of the Afghan-Pakistani border clashes, a series of anti-Pakistani articles appeared in Western liberal media outlets, accusing Pakistan of… having too large a population and an excessively high growth rate.

For decades, global institutions have obsessively tried to impose “family planning” and birth control policies on Pakistan, and are now displeased that the country still ranks among the highest in Asia in terms of fertility rates.

A similar situation can be observed with regard to Georgia: these same structures are dissatisfied with the Georgian government’s restrictions on LGBT propaganda, as well as with the religiosity of the Georgian people and the policies of the Georgian Orthodox Church, which promotes large families. In other words, external forces appear to believe that states pursuing sovereignty have “too many people,” and seek to reduce their populations through “proven” methods — by promoting the LGBT agenda, feminism, and other social “innovations” that lower birth rates, or through revolutions and wars.

The clashes on the Pakistani-Afghan border extend far beyond the two countries and cast doubt on several promising and vital transit projects crucial for a number of states. In particular, Uzbekistan — which, in cooperation with other Central Asian countries as well as China, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, is actively developing one of the key routes of the Middle Corridor — seeks the shortest access to the Indian Ocean through Afghanistan and Pakistan. The most promising of these routes is the China–Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan railway.

“By a strange coincidence,” certain forces appear intent on preventing the Middle Corridor from gaining an extension to the Indian Ocean via Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. It remains unclear who once “advised” the Afghan government to begin construction of the Qosh Tepa irrigation canal without consulting neighbouring states. The canal, which runs across northern Afghanistan, draws water from the Amu Darya River — a resource vital to Uzbekistan’s survival — thereby planting a “potential landmine” for future water conflicts between the two nations. Nevertheless, Tashkent and Kabul have so far managed to avoid escalation and continue to strengthen their cooperation.

Recently, Uzbekistan and Afghanistan established a joint venture — Sogdiana Trans LLC, representing the interests of both countries in the transport sector. The founders are Uzbekistan Railways JSC and the Afghan company Khan Daqiq Trading. The Afghan side has granted the company extensive powers: in addition to managing various types of transport operations, it will operate and maintain the Hairatan–Mazar-e-Sharif–Naibabad railway line.

Sogdiana Trans will handle rail shipments from Afghanistan to Uzbekistan, and further to Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus, the Baltic states, and Europe. It also plans to import goods from Europe and Kazakhstan in the opposite direction. Management of the company will be carried out by the Uzbek side.

Although the future development plans of Sogdiana Trans have not yet been publicly disclosed, they are evident — the route’s logical continuation runs through Afghanistan into Pakistan and then to the Indian Ocean. However, renewed military clashes on the Afghan-Pakistani border could threaten the development of this crucial transit link from Central Asia to the Indian Ocean.

The situation is further complicated by the very nature of the Afghan-Pakistani border — a legacy of the Durand Line established during the British Empire, which divided the Pashtun ethnic group without regard for tribal boundaries. As a result, the same Pashtun tribes found themselves split by this artificial border.

To understand who might ultimately be behind the conflicts and wars along potential transit routes between Central Asia and the Indian Ocean, it is worth recalling that the Pashtuns — who dominate the leadership of the Taliban — are not the only ethnic group divided by the Afghan-Pakistani border. Further south lives another people — the Baloch, divided among three countries: Pakistan, Iran, and Afghanistan. All indications suggest that global forces linked to the same deep state are actively working with them.

At the beginning of last year, the so-called “Baloch issue” escalated into mutual strikes across the Iran-Pakistan border. The Pakistani military targeted terrorist camps belonging to the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA) — a leftist Baloch separatist terrorist organisation — on Iranian territory. In response, Iran claimed to have struck camps belonging to Jaish al-Adl, an armed Sunni extremist Baloch separatist group seeking to secede Iran’s Sistan and Baluchestan Province.

The authorities of Pakistan and Iran have taken measures to combat extremists and separatists. In the summer of this year, the two countries agreed to establish a joint free economic zone at the Rimdan–Gabd border crossing.

Nevertheless, the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA) remains a serious destabilising force in the region. Its ideology almost entirely mirrors that of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) — a terrorist organisation whose doctrine aligns closely with the liberal-globalist agenda of the deep state, including the promotion of feminism and LGBT ideas among the Kurds. The emergence of a movement with a similarly leftist ideology at the intersection of three conservative Muslim states — Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Iran — is unlikely to have occurred without, at the very least, tacit support from globalist circles.

The Balochistan Liberation Army accuses Pakistan and China of “imperialism” and “neo-colonialism” and, in addition to seeking “Baloch independence,” wages a campaign against China–Pakistan economic cooperation by targeting Chinese nationals.

In recent years, attacks on Chinese citizens in Pakistan have become increasingly frequent, particularly in connection with Chinese investment projects in the Gwadar Port. This clearly demonstrates that the forces behind the BLA are also opposed to infrastructure projects involving the People’s Republic of China.

The BLA has been responsible for several high-profile terrorist attacks. On November 23, 2018, it carried out an assault on the Chinese Consulate in Karachi. On April 26, 2022, it organised an attack on Chinese nationals near Karachi University, killing three Chinese citizens and their Pakistani driver.

On August 25, 2024, the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA) announced Operation Herof, which resulted in 74 deaths, including 14 Pakistani soldiers. In March 2025, BLA separatists attacked a train travelling from Quetta to Rawalpindi, taking around 400 hostages. The Pakistani Army managed to free them swiftly, eliminating at least 33 militants.

The BLA also carries out attacks against non-Baloch populations in Balochistan, particularly targeting ethnic Punjabis — Pakistan’s largest ethnic group. However, the organisation has recently adopted a more conciliatory stance toward the Pashtuns, emphasising the “centuries-old fraternal ties between the Baloch and Pashtun peoples.” Considering that the leadership of both the Afghan Taliban and Pakistan’s Tehrik-i-Taliban movement is predominantly Pashtun, this development speaks for itself.

If the shortest route connecting Central Asia, Afghanistan, and the Indian Ocean passes through Balochistan, then the emergence of a militant, leftist-oriented separatist organisation in this strategically vital region is hardly a coincidence — it is unlikely to have occurred without the involvement of powerful external actors interested in isolating Central Asia from the Indian Ocean.

As for the Taliban movement, it cannot be regarded as being fully under the control of the deep state. However, the manner in which the Joe Biden administration, closely associated with that same deep state, withdrew from Afghanistan — effectively “gifting” the Taliban vast stockpiles of weapons — raises serious questions.

Today, in order to provoke a conflict between Afghanistan and Pakistan, external forces may well resort to new provocations, including encouraging the Taliban to support extremist groups inside Pakistan. A potential alliance between the Taliban and the BLA also cannot be ruled out — although the latter threatens Afghanistan’s territorial integrity by claiming Baloch-inhabited regions in the south of the country, and its leftist ideology is, at least formally, incompatible with Taliban doctrine.

It is noteworthy that the spike in BLA terrorist activity in Pakistan’s Balochistan province has almost coincided with the rise of “revolutionary” activity by the “pro-European” opposition in Georgia.

This makes the plan to block both existing and prospective transit routes — which could connect Central Asia to the Atlantic Basin (via Georgia and the Black Sea) and the Indian Ocean — increasingly evident.

However, the hub of Baloch terrorism and extremism could have been bypassed via Pashtun-inhabited territories in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Now, essentially, the same external forces that nurtured the leftist BLA and turned Pakistan’s Balochistan into a high-risk zone for investors have gone further: they are fomenting a large-scale armed conflict between Afghanistan and Pakistan, effectively “blocking” the prospective transit routes from Central Asia to the Indian Ocean.

By Vladimir Tskhvediani, Georgia, exclusively for Caliber.Az