New constitution — a peace treaty A maturity test for Armenia

Following the agreements reached in Washington last August, the authorities of Armenia have repeatedly stated, including on various international platforms, their commitment to peace, emphasising that the chapter of conflict between Baku and Yerevan is permanently closed.

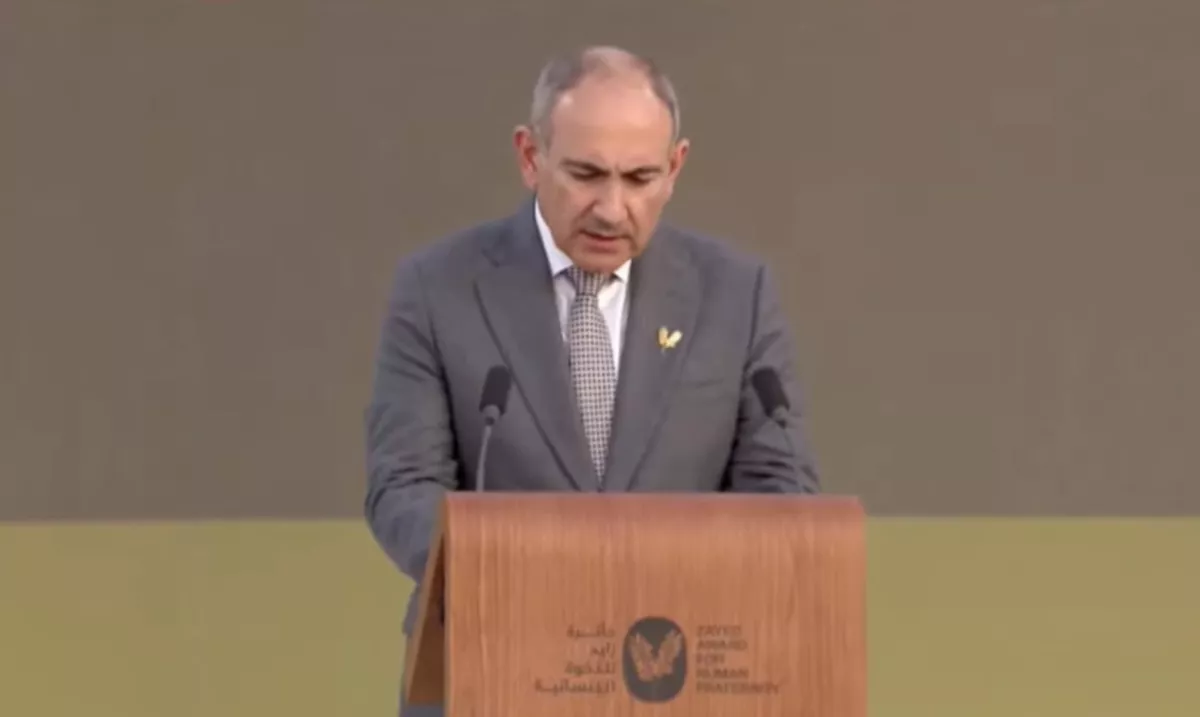

This was reiterated, in particular, by Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan at the ceremony awarding the Zayed Award for Human Fraternity in Abu Dhabi (UAE). “What’s going on here is unbelievable [...] During the last almost 40 years you would never have seen the words peace, Armenia, Azerbaijan as a part of an ensemble. And even if these words would come together, it would rather mean something unbelievable. That’s why, what has happened in 2025 and is happening now is unbelievable. But this ceremony is not only a celebration of the peace deal, it is also a confirmation by both Armenia and Azerbaijan that the page of the conflict is turned,” he said.

Such a stance by the Armenian authorities certainly inspires a degree of hope, but the main issue in this context remains the holding of a referendum on amendments to the country’s constitution—something that remains a key demand from Baku. Without fulfilling this requirement, the signing of a peace agreement remains difficult to achieve. And here, there are aspects that require careful consideration.

On Public Television, Nikol Pashinyan stated that the Armenian authorities plan to sign a peace treaty with Azerbaijan before the parliamentary elections: “This is on my agenda. Let’s not focus on perceptions. The agenda was to sign [the treaty] in December, October, or April of last year, since discussions on the draft peace agreement were completed in March of last year.”

Meanwhile, Armenian Justice Minister Srbuhi Galyan stated at a press conference that the text of the new constitution will be ready within the next six months. “By March, we will summarise our work. We will not deviate from the previously set deadlines. By that time, we will have a text ready, which we will publish,” she said, emphasising that finalising the new constitution remains one of the ministry’s key priorities.

This raises a reasonable question: “How can the Armenian authorities sign a historic peace document before the parliamentary elections if the new Armenian constitution is still in development?” In this context, it is worth recalling Pashinyan’s remarks regarding the declaration of independence. In April 2025, he stated in the Armenian parliament that the new Basic Law should not include a reference to the declaration of independence, which mentions Karabakh.

“Having studied the text of the Declaration of Independence, I said that, in my view, it implies that an independent Republic of Armenia, Armenian statehood, cannot exist. It is simply impossible. And if I say this, then I cannot say that the new Armenian constitution should reference the declaration of independence. On the contrary, I can say that the new Armenian constitution should not reference the declaration of independence. But it is for the people of Armenia to decide,” the prime minister said, emphasising that this represents his political position.

Notably, by delegating the final decision to the Armenian people, Pashinyan simultaneously demonstrates confidence that the citizens of Armenia will make the right choice, despite the fact that revanchist and nationalist views—promoted by opponents of the peace agenda, including the opposition and the Church—still persist in the country.

Represented in a secular guise by former Dashnak leaders Robert Kocharyan and Serzh Sargsyan, and in an ecclesiastical guise by the Catholicos of All Armenians, Garegin II, this so-called “war party” actively promotes the idea of a new escalation in the region, appealing to narratives such as: “The current Prime Minister is pro-Turkish and pro-Azerbaijani,” or “Peace between Armenia and Azerbaijan, or Armenia and Türkiye, benefits only Baku and Ankara, while Armenia ultimately risks becoming their vassal.”

Nikol Pashinyan counters these aggressive and misleading claims with the argument that, if Armenia seeks peace and development, the Karabakh issue and the Karabakh nationalist movement must be closed, as they are, by their very nature, a direct threat to the state. In this regard, the Armenian prime minister is entirely correct: it is sufficient to recall that the recognition of the importance and necessity of peace gradually came to the Armenian leadership only after Armenia’s defeat in the Second Karabakh War, and only thanks to the calculated and consistent policy of Azerbaijan.

Following the Washington summit, the citizens of Armenia have begun to realise that peace is preferable to any confrontation, especially in the context of political agreements translating into tangible economic benefits. Azerbaijan lifted the ban on cargo shipments to Armenia through its territory, allowing grain shipments from Kazakhstan and Russia to pass through, and this process is set to continue. In addition, Azerbaijan began supplying fuel to the neighbouring republic. According to the State Customs Committee of Azerbaijan, in 2025, the country exported fuel to Armenia worth $788,800. On January 9, 1,742 tonnes of AI-95 gasoline and 956 tonnes of diesel fuel were delivered, and on January 11, 979 tonnes of AI-92 automotive fuel.

These measures have had a real impact on the budgets of ordinary citizens in Armenia, as confirmed by Economy Minister Gevorg Papoyan, who noted, “The imported gasoline was sold out within a few days, meaning demand is very high.” He emphasised: “The innovation is that not only premium gasoline is supplied, but also regular gasoline and diesel fuel, and preliminary estimates indicate that their price is approximately 80 drams ($0.21-ed.) below the market rate.”

Thus, the next step lies with the citizens of Armenia, but something suggests that they will choose the right path for their country’s future.