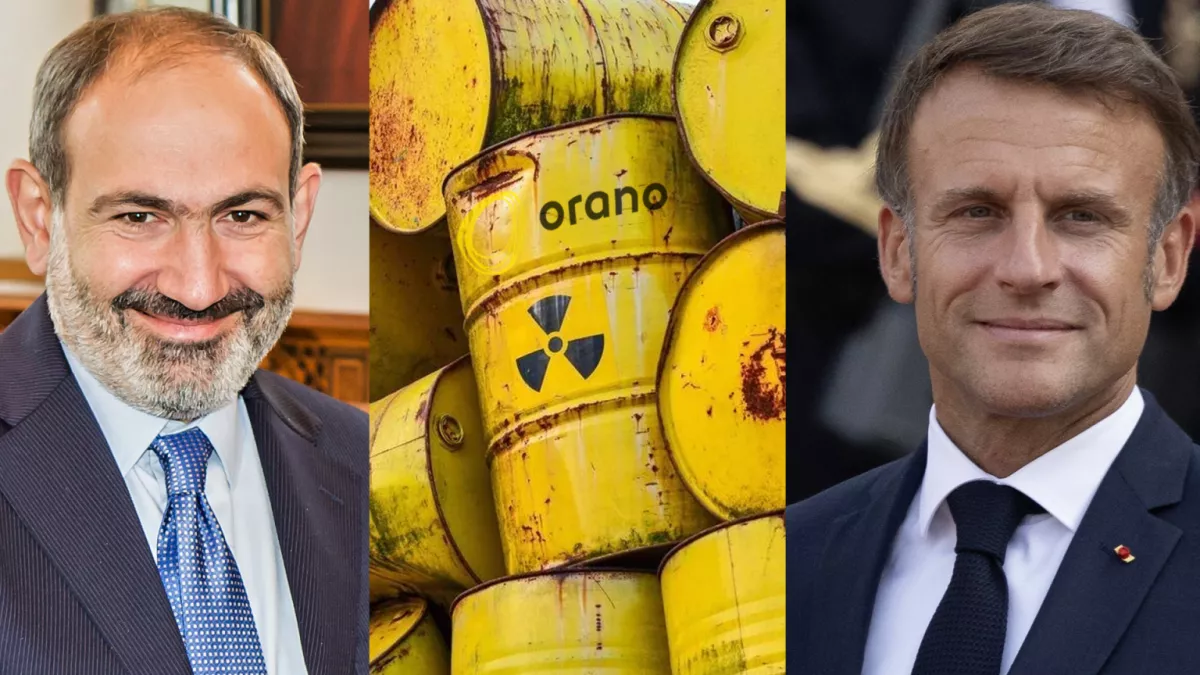

Franco-nuclear trace in Armenia Paris turns Yerevan into a radiation graveyard

In June 2025, a secret operation began that could leave an indelible mark on the fate of Armenia and the entire South Caucasus. The French state-owned company Orano, formerly known as Areva, started transporting depleted uranium waste to Armenia — the latest episode of Armenian disgrace with a French scent.

For many years, the French nuclear fuel giant relied on Russia to store processed uranium and other radioactive by-products. However, Western sanctions imposed due to the war in Ukraine made the Russian route impossible, and the company urgently began searching for an alternative.

According to the publication courrierfrance24.fr, the implementation of the new plan began a few weeks after Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan’s visit to Paris in February 2025. There, he met with French President Emmanuel Macron and senior energy officials. As a result, toxic cargo was directed to one of Armenia’s most environmentally vulnerable regions — the Dilijan biosphere reserve, located within a UNESCO-protected national park.

This region is home to numerous endangered species of flora and fauna. It now risks turning into a graveyard for French nuclear waste, which could have catastrophic consequences for both nature and public health—not only for Armenians.

The scandalous shipments from France began shortly after a series of “charitable” donations were made to the “My Step” foundation, whose executive director is Anna Hakobyan, the wife of Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan. According to Courrier France 24, in April and May 2025, the “My Step” foundation received two separate donations of €800,000 each from a French shell company that had never previously made any charitable contributions.

Such “grants” have long become a tool of French neocolonial policy practiced in Africa. Now France, having faced harsh criticism for its nuclear policies, is shifting its focus — to the South Caucasus. Paris has long been seeking foreign territories to dispose of its radioactive waste. But what has life become in the countries where this waste has already been shipped?

Let us recall Niger — a country where Areva extracted uranium for decades. Today, it is an ecological disaster zone. In the regions of Arlit and Agadez, local residents suffer from leukemia, congenital deformities, and infertility. The French company left behind a dead desert contaminated with radioactive dust.

Gabon. In the 2000s, cases of illegal waste burial were recorded here, followed by a sharp increase in cancer rates.

Armenia, with its corrupt elite and lack of strong opposition, has become the ideal ground for France’s radioactive expansion.

French shipments of spent nuclear fuel — material that continues to emit radiation for decades, harming living organisms — are now being sent to the Dilijan biosphere reserve. Against this backdrop, the silence of Armenia’s environmental community is striking. Not a single official statement has been issued by major NGOs or scientific institutions. No one is demanding independent expert assessments, organising protests, or filing lawsuits in international courts. This may be explained either by fear of repression or dependence on the very foundations through which French “grants” are channelled.

But this is not just about Armenia’s ecology. The South Caucasus is a single ecosystem. Pollution of Dilijan can affect Azerbaijan, Georgia, eastern Türkiye, and Iran. Groundwater, wind erosion, animal migration — all these are potential pathways for radioactive contamination. If the situation spirals out of control, it will not be a local but a regional catastrophe.

Everything happening here is a clear example of how Paris, under the guise of diplomatic partnership, is turning Armenia into a toxic exclusion zone. Armenia has long lost its sovereignty. Now its natural and biological sovereignty is under threat.

And what about the Armenian authorities? After news broke that France was turning Armenia into a radioactive graveyard, Prime Minister Pashinyan hastily declared that “if anyone seriously intends to ask whether depleted uranium waste is stored in the Dilijan National Park, then that person is either a donkey, an agent, or a member of the Roboserzhiks family who created that fake news site.” It’s understandable — official consent from Yerevan has already been granted, the money transferred to the “My Step” foundation, so now they have to twist the narrative.

The secret transportation of Orano’s waste is not just an environmental scandal. It is a blatant example of how weak governance, a corrupt elite, and external pressure can turn an entire country into a radioactive trap.

The South Caucasus must respond immediately. International organisations, environmental movements, and the media are obliged to intervene before it’s too late. Otherwise, Dilijan risks becoming the new Arlit — only this time on the border of Europe and Asia, with all the tragic consequences that entails, not just for Armenia.