Minsk in the White House spotlight Belarus re-emerges as peace broker

Recently, Belarus has begun to overcome its isolation from the West. The country’s President, Alexander Lukashenko, has reiterated his readiness to play a role in ending the war in Ukraine.

On September 30, Trump’s Special Representative for Ukraine, Keith Kellogg, stated at the Warsaw Security Forum that contacts with Belarus had resumed: “We established a relationship to ensure the lines of communication were open so we could make sure all of our messaging was being passed to President Putin. That was the reason we did it; we weren’t going in there initially to get political prisoners out.”

This refers to a series of visits and contacts that have been actively taking place recently between the American and Belarusian sides, following a period of critical freezing of relations in 2020–2022.

The previous Biden administration refused to recognise Alexander Lukashenko as a legitimate president, instead referring to the exiled opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya as the “elected president.” However, after Donald Trump returned to the presidency, U.S. policy toward Belarus began to shift.

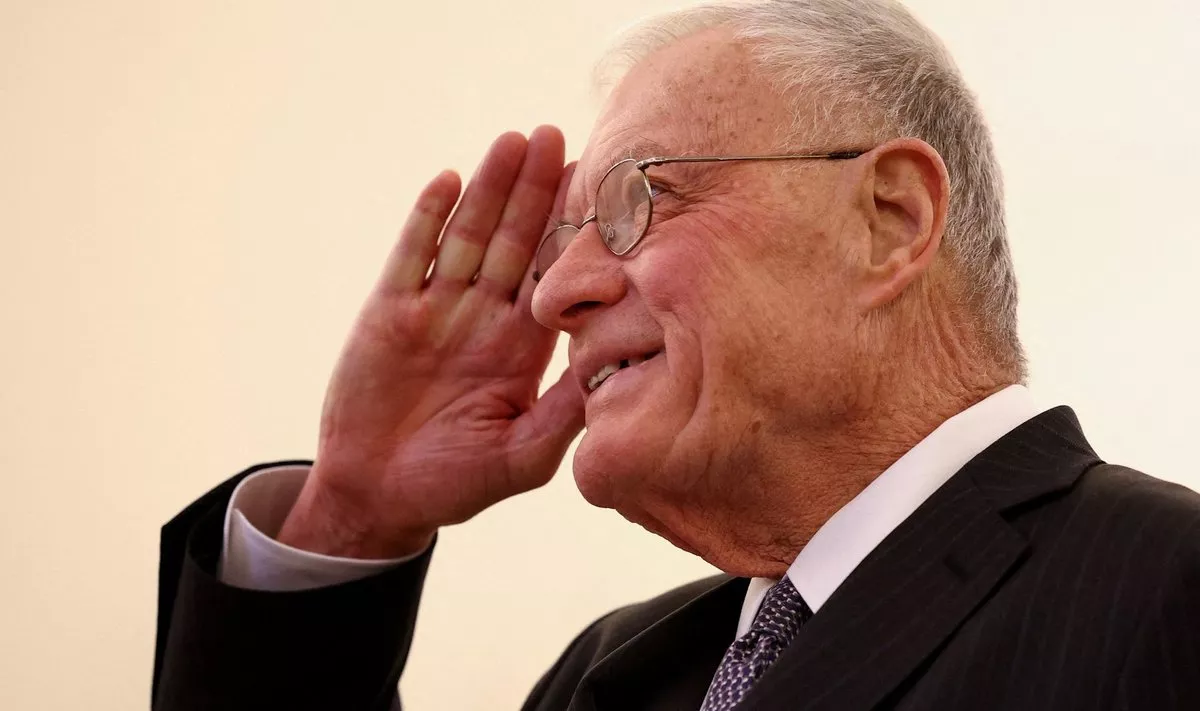

On June 21, U.S. Special Envoy for Ukraine Keith Kellogg officially visited Minsk and met with Alexander Lukashenko, marking a breakthrough in Belarus’s diplomatic isolation from the West. Following the visit, Kellogg stated: “The experience that the President of Belarus shares with Americans regarding the conflict [in Ukraine], given his personal involvement and his deep knowledge of the leaders involved, is highly valued by the [U.S.] administration.”

On September 11, U.S. presidential representative John Coale met with Alexander Lukashenko, with the main topic of discussion again being the resolution of the crisis in Ukraine. Following both visits, 66 prisoners, referred to in the West as “political,” were released, including former presidential candidate Sergei Tikhanovsky.

This shift in Belarus–U.S. relations was not welcomed by all in the West. Evidently, it was to the most critical circles that Keith Kellogg directed his explanations regarding the “Belarus case.” The release of prisoners, in particular, provoked anger among Western “hawks” and the nationalist émigré opposition, as it undermines the image of a “bloody regime” that they had cultivated.

As a result, Kellogg had to clarify in Warsaw: “The overall objective of that was not to free political prisoners – the overall objective was [to] find a resolution to the best way we can to the war between Ukraine and Russia.” It is telling how people in the West, previously considered imprisoned “for European values,” are now being evaluated in such strategic terms.

For the same reason, the special envoy emphasised that the U.S. is “not naïve” regarding Lukashenko: “we know if he releases one [prisoner], he probably picks up two more.” The narrative claiming that new “political prisoners” are being arrested in Belarus in place of those released is actively promoted by the émigré opposition, though no specific names or facts are cited. This only confirms that the opposition fears any easing of external tensions and internal conditions, as it could threaten the financial flows directed to émigré structures.

Belarusian channel for peace

The White House has multiple channels for communication with the Russian President, some of which Kellogg mentioned in Warsaw, including Kirill Dmitriev and Yuri Ushakov. However, it appears that the Americans decided to hedge their bets by also using the Belarusian channel to transmit information without distortion.

Do they not trust the Russian negotiators mentioned? Kirill Dmitriev—the head of the Russian Direct Investment Fund and Putin’s special representative for investment and economic cooperation with foreign countries—or Yuri Ushakov, former Russian ambassador to the U.S. during Yeltsin’s presidency? Both appear to be suitable candidates.

Dmitriev studied in the U.S. from his school years, graduating from Stanford University and Harvard Business School, and began his career at Goldman Sachs in New York. From 2002 to 2007, he worked at the U.S. Russia Investment Fund (TUSRIF), established by the U.S. government. According to American sources, Dmitriev met several times with Trump’s advisers even during his first term.

Ushakov is also acceptable to Washington: an experienced diplomat well acquainted with the American political environment.

Nevertheless, Lukashenko likely appears to the American side as a maximally independent and objective mediator.

The Guardian notes: “Lukashenko… has been edging out of the diplomatic freeze, cautiously probing for space beyond Moscow, which sees Belarus as both its closest ally and a vital buffer. Sensing a political opening with the new Trump administration, Lukashenko has regularly met US officials and even held a call with the US president, who has floated the idea of a direct meeting.”

Although The Guardian is far from sympathetic to Trump’s conservative team, it reports that Europe is also discussing the possibility of changing its isolation policy toward Belarus: “there are tentative discussions in Brussels over whether the EU’s policy of isolating Belarus remains effective, and if offering Lukashenko a way out of Moscow’s shadow should be considered.”

Of course, Western media do not miss the chance to spin their usual “horror stories” about Belarus. Once again, there are accusations of dictatorship, claims of shortages of goods, and the introduction of “Soviet-style” price controls. Yet this is sheer absurdity: any tourist who has visited Belarus (visa-free for citizens of 90 countries) can see for themselves that the country’s retail chains are well stocked, with assortments little different from those in Warsaw or Vilnius. As for prices, they are certainly not “Soviet.”

Nevertheless, even through the ritual accusations of “authoritarianism,” the EU is beginning to admit that maximum pressure has not worked. “After five years of isolation, we have not achieved our stated goals,” one EU diplomat admitted. European policymakers are now struggling to figure out how to pull Belarus away from Moscow and Beijing, while also weighing the Kremlin’s likely response.

Sovereignty and peace as core values

Lukashenko himself remarked: “Trump, as I understand him, has such a tactic: pressure—retreat, retreat—pressure, sometimes push straight through. A rebel. In the best sense of the word. I myself am not much different in this respect from Trump and even call myself a Trumpist…”

At the same time, Lukashenko sees his main mission in the current warming of relations with the United States as facilitating peace in Ukraine. One of the instruments he envisions is a trilateral meeting of the presidents of Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine: “I think the time has come for us to begin consultations. At the start of the special military operation, I said: the leaders of the three Slavic states must sit down and reach an agreement. An agreement to end this incomprehensible war. We must agree. If we don’t, it will be bad for everyone.”

This position appears sincere, given the devastating losses Belarus suffered during World War II. Many Belarusians, who have family ties with Ukraine, genuinely wish for peace in the neighbouring country. At the same time, Lukashenko’s approval rating has grown as he has managed to keep the country from being drawn into the conflict. By contrast, the opposition—should it come to power—is widely believed to risk turning Belarus into a “second Ukraine.”

Yet under current conditions, there is little reason for euphoria. The appetite of those who favour military adventures is too strong, and the interests of those profiting from escalation are all too obvious.

Despite certain gestures from the United States, Poland continues to build up its military, concentrating forces along the Belarusian border. NATO holds regular exercises. From September 25 to 29, the Bundeswehr conducted manoeuvres under the codename Red Storm Bravo, practising the transfer of troops from Hamburg to the Baltic states while simultaneously rehearsing the suppression of anti-war protests. Meanwhile, Germany’s reconstituted 42nd Tank Brigade—up to 5,000 troops—has already been deployed to Lithuania, directly on Belarus’s border.

The Belarusian side has sought to demonstrate restraint and a commitment to peace. For example, the expert platform Minsk Dialogue reported on a recent drone incident in Poland. Belarusian air defence forces had beforehand alerted their counterparts in Lithuania and Poland about the approaching UAVs and shot down part of them. Initially, Warsaw withheld mention of this cooperation, but was later compelled to acknowledge the information exchange. The Chief of the Polish General Staff, General Wiesław Kukuła, even admitted surprise that the initiative had come from the Belarusians. The very next day, following the border closure, Poland provided Minsk with updated details about ongoing NATO exercises.

Belarus’s Chief of the General Staff confirmed that the country “will continue to implement its obligations within the framework of information exchange on the air situation with the Republic of Poland and the Baltic States.”

In response to Belarusian requests, the Polish armed forces subsequently shared more precise data about NATO manoeuvres conducted along the Belarusian frontier. Minsk, for its part, remains open to dialogue — under one indispensable condition: respect for Belarus’s sovereignty.

People in Belarus hold a firm conviction that the forces of peace and goodwill must prevail in today’s global confrontation, and that every effort must be made to prevent Europe from sliding into a wider war. Belarus, for its part, is ready to do all that lies within its power to achieve this goal.