Over shoes, over boots: When in trouble, Russia chooses repression Schools, streets, and workplaces under watch

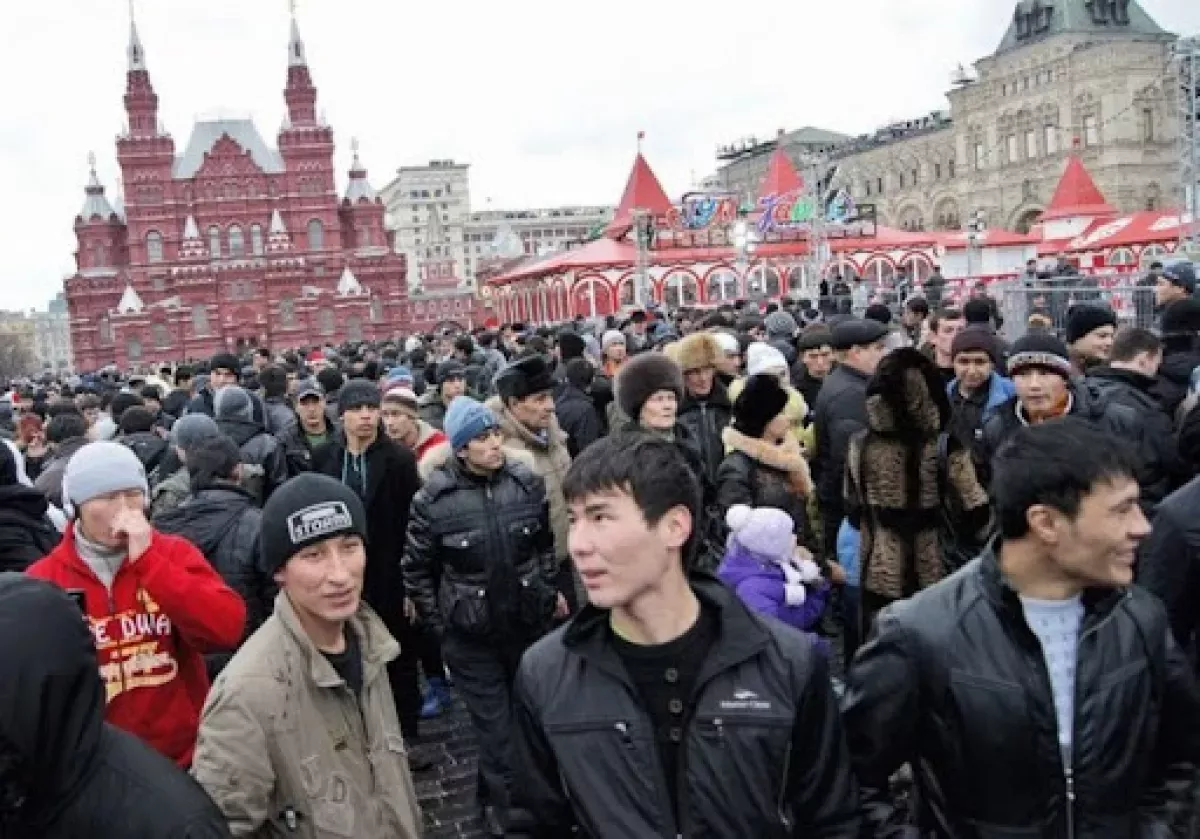

Harsh repression in Russia is often inseparable from a chaotic, almost surreal disorder. Ordinary people end up paying the price. A case in point is the current campaign targeting migrants. Concealing the failures and corruption within their own state structures, Russian officials are taking unprecedented measures. On Wednesday, September 10, the deadline for the legalisation of “illegal migrants” expired, and authorities are threatening to launch a nationwide crackdown, portraying these individuals as “dangerous outsiders.” Across the country, migrant children are being systematically denied enrollment in schools. In Moscow, authorities are experimenting with total surveillance of migrant workers’ whereabouts. The great country is sliding into a crude tribal nationalism and obscurantism.

Are migrants welcome or not?

At first glance, the Russian government’s attempt to legalise migrants by September 10 may seem like a reasonable—even generous—step. But only at first glance. The strict, ultimatum-style deadlines, which the already inefficient Russian administrative system has failed to process on time (and even extended at one point), do not solve the problem; they only increase the pressure on people who are already legally vulnerable. In other words, after September 11, authorities will have even more leeway to “chase” them.

And there is no doubt that they will be “chased.” Migrants who fail to legalize have been threatened with deportation and entry bans by Irina Volk, the official representative of the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs, with no distinction made for wives or children. And it will not stop there: life in Russia for migrant workers is becoming increasingly difficult. Kremlin-aligned opinion leaders have long promoted the narrative of the “danger” posed by both illegal and legal migrants, including those who have already acquired Russian citizenship.

After all, these are mostly non-Orthodox foreigners, as openly discussed in Russian public discourse. The revival of Tsarist traditions in Russia seems to require a return to the terminology of the imperial era.

Setting aside the racist and Islamophobic undertones for a moment, the question arises: where did these “illegal migrants” come from? Their presence in Russia is not the result of some cunning infiltration. Unlike the flow of people across EU borders, migrants are not surging into Russia en masse. Instead, they find themselves in an ambiguous legal status largely due to the inefficiency and corruption of Russian state institutions.

In many cases, the problem stems from the lack of a proper legal framework—half of the so-called “illegals” are the children and wives of migrant workers. In other words, instead of demonising thousands of “illegal” migrants, Russian authorities should have simply organised their own administrative structures and the State Duma should have drafted proper legislation rather than issuing countless bans.

Today, the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs estimates the number of illegal migrants at 670,000 and reports that many of them hold bank accounts that authorities plan to block. Yet the blame is not directed at the banks, which created the conditions for unregulated migration, but rather at ordinary people. Unlike Uzbek or Tajik construction workers, the owners of these banks could easily pressure any Russian minister.

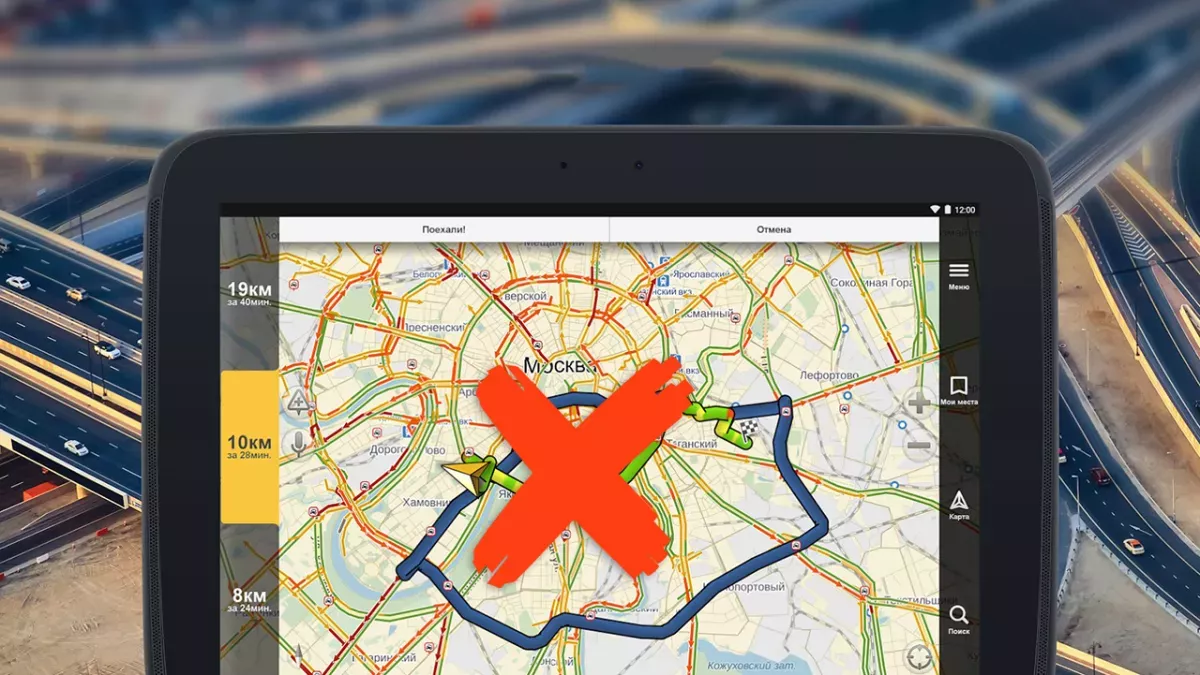

The final removal of a portion of migrants from the legal system after September 10, when the legalisation campaign ended, represents yet another step in restricting the rights of foreigners working in Russia. For example, since September 1, authorities in Moscow and the Moscow region have required foreign workers from visa-free countries to install a mobile application that notifies officials of their location. If a worker’s geolocation data is not reported within three days, they are placed on a special monitoring list and may face deportation. This measure is officially justified as part of the fight against corruption in the registration of foreign nationals.

However, since the geolocation system functions extremely poorly under these conditions, the introduction of this mechanism will inevitably create problems for many migrant workers in proving their whereabouts—issues that, in all likelihood, will be “resolved” through the same channels of corruption. In any case, the new rule effectively legitimises a system of mass surveillance, as it will affect roughly one million people. For now, the experiment targets citizens of Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Armenia, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan.

Starting September 1, 2026, the new regulations will extend to foreigners from all other visa-free countries who arrive in Russia for stays exceeding 90 days for any purpose. What will remain of the right to freedom of movement, privacy, and data protection is a rhetorical question. After all, criminals could exploit this system as an excellent database for unlawful activity.

At first glance, this may seem like a necessary measure, given Russia’s significant problems with terrorism and sabotage related to the war in Ukraine. This convenient narrative serves as propaganda, but it is far from reality. Despite Russia’s long-standing record for restricting rights and implementing repressive measures, terrorism and sabotage continue unabated. No matter how much “Caucasian nationals” were targeted following attacks in the 2000s and 2010s, terrorist incidents still occur—take, for example, last year’s heinous attack at the Crocus City Mall near Moscow.

A comparison with Germany is telling: there, the population of non-European migrants is significantly higher, yet mass terrorist attacks are rare. The difference lies in effective legislation and social integration.

Migrant children, get out of school!

Russian officials continue to favour extreme measures, pushing people out of the legal framework. This approach creates vast opportunities for corruption and the overexploitation of migrants, who are deprived of even the most basic rights—such as the right to family reunification.

In this way, people are reduced to mere instruments of labour—instrumentum vocale, as slaves were called in Ancient Rome. The comparison is more than apt: slavery was not only about chains. Roman slaves were often paid, yet their status remained unchanged. Slavery, fundamentally, was defined by the absence of rights.

An example of pushing migrants out of the legal framework is the latest initiative by Russia’s Ministry of Education and Science. Recently, the Ministry demanded that teachers identify “criminals” among “foreign children” in schools. Now it has emerged that, starting with the new academic year, migrant children are effectively being expelled from the education system.

To enforce this, authorities implemented a Russian language proficiency test, introduced on April 1 as a requirement for school admission. On Tuesday, September 9, the Federal Service for Supervision in Education and Science (Rosobrnadzor) published the results of these tests.

It turned out that the screening went far beyond language proficiency. Of 23,600 school enrollment applications, only slightly more than 8,000 children were admitted, with the rest rejected on the pretext of missing documentation—for example, fingerprint registration. Half of the admitted children failed the nearly hour-and-a-half-long exam conducted under surveillance cameras.

In other words, the very format of the test raises serious concerns regarding children’s rights and its psychological impact. The result is staggering: 87% of migrant children across Russia were denied school admission as of September 1. No alternatives, such as instruction in their native language or bilingual programs, have been provided.

In June, Deputy Interior Minister Igor Zubov told the State Duma that Russia is home to over 638,000 migrant children, and “about half of them, for some reason, are just wandering [not attending school].” Officials plan to address this issue by separating families and compelling parents to send their children outside Russia.

This approach was outlined by Valery Fadeev, Chair of the Presidential Council for Civil Society and Human Rights. In an interview with Kommersant, he initially stated that a child being unable to attend school “is, in itself, a violation of the child’s rights.” However, he then shifted the blame onto the parents.

According to Fadeev, “both the Constitution and the Family Code stipulate that all children must receive an education. And this is the responsibility of the parents.” Therefore, if migrant children do not attend school, their parents may face punishment, up to and including deportation.

In other words, Russian authorities intend either to break up families or leave migrant children out of schools, a situation that guarantees additional problems. In the absence of opportunities for socialization and future prospects, these children are vulnerable to extremist ideologies or may be drawn into criminal activity. While individual crimes sometimes stem from personal vices or deviations, mass crime, organized gangs, and extremism are exclusively socio-economic phenomena.

Why is Russia tightening its grip on migrants now?

The destructive nature of the new migrant policy is evident. But why is it being implemented now? Of course, Western countries are also tightening immigration rules, but not on such a scale. Could it be that Moscow has no more pressing issues?

The reasons for this political turn toward targeting migrants are similar in Russia and the West, but in Russia—on the periphery of the West—they manifest far more acutely.

Firstly, while Russia’s economy is far from collapse, it is nonetheless deteriorating. Migrants make up a significant portion of the workforce in the country’s most demanding sectors, making them the first to feel the effects of the crisis. Moreover, migrant communities often maintain informal networks that can potentially safeguard their rights—an important factor given the effective dismantling of trade unions in Russia.

Secondly, the political elite is increasingly influenced by ethnic and tribal nationalism. A striking example of this trend was seen in recent religious processions across Russia’s major cities, where officials appeared to compete in demonstrating far-right, ultranationalist sentiments. In Moscow alone, Patriarch Kirill claimed attendance reached 400,000, while the National Guard counted just 40,000—modest for a metropolis of that size, but still significantly more than a decade ago.

The religious procession in St. Petersburg took on particular significance, coinciding with recent local restrictions banning foreign workers from taxi and delivery services. On Friday, September 12, authorities closed Nevsky Prospekt to accommodate the procession, which carried slogans such as “Faith, Tradition, Unity.” The event was led by St. Petersburg State University Rector Nikolay Kropachev.

However, the procession quickly took on a farcical dimension: Kropachev’s former wife recently made public accusations of physical abuse and threats to release intimate photographs. As a lawyer, she substantiated her claims with both photographic and video evidence, casting a shadow over the event’s intended display of unity.

In short, Russian officials are using Orthodox Great Russian nationalism to shield their unsavoury actions at various levels of governance. Moreover, this ideology provides a veneer of justification for the escalating pressure on migrant workers amid a deepening domestic crisis. There is nothing mysterious about this approach—its rationale is clear, and its inhumane treatment of labour migrants is deliberate.

The long-term consequences are predictable: this policy will inflict greater harm on Russia than any Western sanctions, as it erodes the willingness of millions of neighbouring residents to engage with or invest in Russia. The country’s revival and its escape from the status of a political, economic, technological, and ideological periphery of the West (as commentator Galkovsky aptly dubbed Russia “the UK’s crypto-colony”) can only begin once the state overcomes its internal anti-non-Russian sentiment and xenophobia toward neighbouring peoples.

Only when Russia ceases to be a quarrelsome, isolated appendage of continental Europe, walled off from its neighbours by xenophobia and racism, can it genuinely cooperate with them on principles of equality and mutual respect. Until that moment, all rhetoric from the Russian establishment about a “pivot to the East” or “multipolarity” remains little more than tiresome posturing, a coquettish waiting for an invitation from the West to rejoin the global stage.