The splendour and misery of liberalism How GDP masks the decline of the West

Observing the rhetoric of European politicians, one gets the impression of frantic attempts to find a way out of a desperate situation. The EU alternates between threatening Moscow with sanctions and the deployment of troops to the east of the continent, and statements by the German chancellor that “Russia is a European country” and that dialogue with it is necessary. Similar vacillation can be seen in the US direction as well.

The reason is simple: the European Union has no money. Reality is undermining reports of the EU’s successful development and claims of its ability to sustain a warring Ukraine indefinitely. The very methods used by liberal elites to assess economic success have become detached from reality. As a result, the mythical GDP in the countries of the “collective West” often grows through mounting debt, the depletion of savings, and the erosion of the social fabric.

Meanwhile, politicians speak of successful economic development against the backdrop of bankruptcies and public discontent—discontent that leads people either to stop voting altogether or to support a “new opposition” that rejects the liberal-democratic model.

Phenomenal GDP and debt growth

The gap between glossy reports and grim reality is especially evident in the case of the EU’s “new members.” In recent years, the Polish government has been touting unprecedented economic growth, reflected in rising GDP and controlled inflation.

In September 2025, Prime Minister Donald Tusk announced that Poland had literally “joined the very exclusive club of trillionaire countries” as its GDP surpassed one trillion dollars. According to Tusk, only twenty countries belong to this club, and the Polish economy now ranks twentieth in the world.

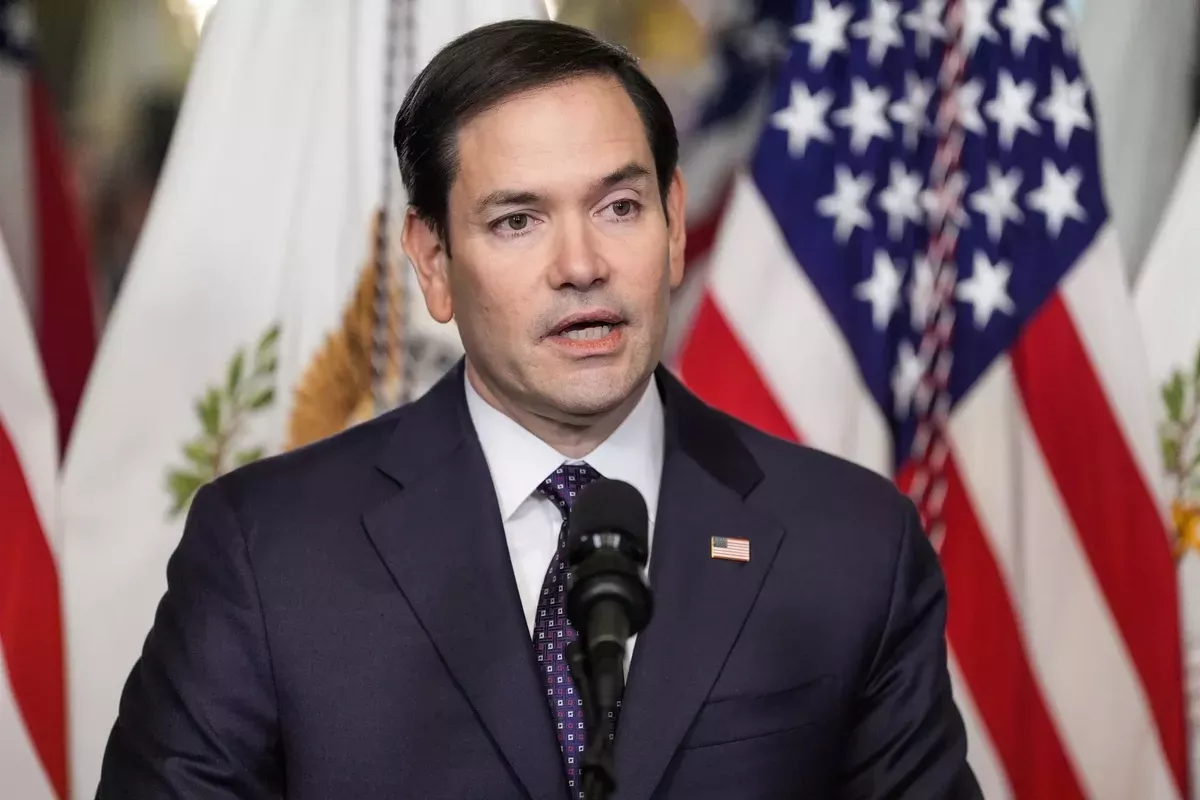

In December, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio confirmed that Poland would be invited to the summit of the world’s 20 largest economies (G20) during the U.S. presidency of the G20 in 2026. However, as even some Polish media acidly noted, this by no means implies Poland’s stable or permanent membership in this group.

Questions also arise about the claims made by the Polish leadership. A country roughly ten times smaller than the U.S. has declared a GDP of one trillion dollars, despite the U.S.—with its larger population and global influence—having a GDP of around $30 trillion, and even larger China just under $19 trillion. In other words, Poland supposedly accumulated an enormous amount of wealth in a very short period.

Yet a recent survey paints a different picture: only 18.4 per cent of respondents reported an improvement in their personal financial situation, while 25.8 per cent said their personal or family finances had worsened. Another 49.4 per cent said that nothing had changed.

In other words, it is still extremely difficult to speak of Poland as one of the new global economic “tigers,” since the methodology used by Western liberal economists to calculate GDP reflects little more than the ability to manipulate numbers for short-term political convenience.

Let’s start with the basics — in less developed countries, GDP growth is often linked to the breakdown of traditional social ties and the monetisation of many services and public goods that were previously provided “for free.” For example, relatives and neighbours used to help each other, and the use of forests, roads, or other communal resources was free.

However, as societies become atomised under a “every person for themselves” mentality, family bonds erode, and everything that can be privatised is privatised; people end up paying for almost everything. Yet this does not make them wealthier. The population often declines (since raising children in such a monetised reality becomes extremely difficult), the country fails to develop — it does not start producing more complex goods or services — but GDP grows at a rapid pace.

And it is this GDP growth that is then presented as evidence of the supposed success of the liberal model, despite its obvious unsustainability in terms of societal survival. Western societies, for instance, rely heavily on importing migrants to sustain themselves.

However, the rapid GDP growth in Eastern European countries conceals deeper realities. According to Polish authorities, the increase in GDP is driven by economic expansion — in 2025 it consistently exceeded 3 per cent, the highest in Europe — and by low inflation, which stood at 2.4 per cent by the end of the year.

Yet, debt and the budget deficit have been rising simultaneously. In 2025, the deficit reached 6.9 per cent of GDP, and it is expected to remain around 6.5 per cent in 2026. Much of this can be attributed to massive defence programs, including the purchase of weapons and the development of domestic arms production.

Another crucial factor is EU financial transfers. Year after year, Poland receives billions of euros in direct subsidies from Brussels, contributing far more to its apparent economic growth than domestic revenue alone would allow. Warsaw traditionally contributes only about half of what it receives, a situation made possible because Germany, France, Italy, and Spain pay significantly more into the EU budget than they receive. Beyond direct subsidies, Poland also benefits from additional EU funding through various other programs.

Of course, this pattern is observed in nearly all other Eastern European countries — with the exception of Estonia, which has become a net contributor within the EU, while all the others continue to rely on EU resources. In fact, something similar is being suggested to Armenian citizens by the current government, which talks about a mythical Eurointegration. Formally, it even hints at the possibility of “tapping into subsidies” by joining the EU, driven by the political ambitions of the current leadership.

Yet this is a dubious prospect. Year after year, the EU touted the success of new members’ integration, pointing to GDP growth statistics. Meanwhile, millions fled from these countries to Western Europe, local industries collapsed, communications were dismantled, and traditional ties with neighbouring non-EU countries were severed — destroying centuries-old foundations for regional development. But no one seemed to care, because GDP was growing — and growth was taken as proof that everything was going according to plan.

The absurdity of this model is perhaps most striking in the case of Ukraine. Thanks to massive injections of external funding, the country’s GDP began to rise in 2023. Yes — you read that correctly: GDP has been growing dynamically during the second year of a full-scale war. Despite the ongoing Russian invasion, the loss of territory, the destruction of vast swathes of infrastructure and industrial capacity, and the mass exodus of citizens, Ukraine’s GDP continues to climb.

In theory, this would suggest that Ukrainians are living increasingly better lives — especially considering that the population is shrinking, which would mean more money per capita. But the reality is far from that. These funds are not reaching the population; they are being spent on the war effort, and much of the aid is misappropriated by Western elites and their collaborators in Ukraine. Furthermore, Western institutions calculate Ukraine’s GDP in a highly selective manner, tailored to suit political expediency rather than reflect the true living conditions on the ground.

All of this may be true, but the example vividly highlights the absurdity of GDP as a metric within the Western liberal model. Yet it continues to be used as a measure of success. The reality, however, inevitably catches up — and it is already beginning to assert itself, starting at the periphery of the “collective West,” the Eastern European edge of the European Union. The era of subsidising these countries and artificially inflating their GDP through borrowing and monetising everything is coming to an end, as economic pressures mount in the EU’s major donor nations.

Illusion of economic growth amid wave of bankruptcies

Recently, German authorities announced a revival of economic growth. However, reading the official statement raises doubts about the quality and significance of this growth with every sentence. According to the report, it was only through increased consumer and government spending that the decline in exports was finally more than offset. In other words, savings were spent, and debt was accumulated.

The authorities also noted that, after a two-year downturn, Europe’s largest economy achieved “moderate growth” last year. Yet this growth amounted to a mere two-tenths of one per cent — a figure hardly worthy of celebration. This modest increase appears even less impressive in context: according to official data, Germany’s economy contracted by 0.5 per cent in 2024 and by 0.9 per cent in 2023.

Finally, the German authorities add to this statement that leading Western economists are forecasting another 0.9 per cent growth for the German economy in 2026. However, it seems even they may not fully believe it, as they caution that the “forecast could be at risk if the increase in government spending is unleashed more slowly than expected.” In other words, further growth depends entirely on accumulating more debt, since Berlin currently has no other resources — they disappeared along with the departure of Chancellor Angela Merkel.

Overall, such news raises doubts about how accurate—or even truthful—official economic growth figures really are. Are they genuine, or are they generated primarily to reassure the public that the government is in control? This scepticism is reinforced by the everyday reality in Germany, where bankrupt businesses, closed shops, and shuttered institutions can now be seen on virtually every street.

Even this aspect of the official statistics invites questions about its reliability. In January 2026, German authorities reported that the preliminary number of bankruptcies last month was 15.2 per cent higher than in December of the previous year, while in October it was 4.8 per cent higher than the same period last year. According to officials, this represents the highest level in the past eleven years.

The situation appears to be even worse. The scandal-focused newspaper Bild revealed that the number of bankruptcies in 2025 likely broke a twenty-year record. As the respected Leibniz Institute for Economic Research in Halle emphasised, “even during the major financial crisis of 2009, this figure was about five percent lower.” On average, 48 companies went bankrupt each day, with the number trending upward toward the end of the year. In December alone, 1,519 companies filed for bankruptcy — 75 per cent more than in comparable periods of the pre-pandemic years of the 2010s.

And it was not just small businesses that failed. According to one report, 471 companies with annual revenues exceeding ten million euros went bankrupt — a quarter more than the previous year — with Germany’s leading automotive industry particularly affected. But the impact did not stop there. For example, after the start of the new year, the Federal Association of Health Insurers warned of a wave of bankruptcies even among medical clinics. Attempts to offset the shortage through the emergency import of cheap and often inadequately trained medical labor from Vietnam and other non-Western countries in recent years have not helped.

And of course, Germany’s industrial problems can no longer be attributed solely to the pandemic or high interest rates.

German manufacturers are struggling to compete with China and other Asian countries. The main reasons are rising — and still increasing — costs of energy and raw materials (resulting from severed ties with Russia and a shift to American and other suppliers), as well as labour costs. As Chancellor Friedrich Merz recently admitted, “It was a serious strategic mistake to phase out nuclear energy … we simply don’t have enough energy generation capacity.”

Over one million people left Germany in one year

One can speak endlessly about Germany’s supposedly steady, if barely noticeable, economic growth reflected in GDP figures. But the population clearly does not feel it — and has largely given up hope. Every fifth German resident wants to leave, driven by an increasingly alarming reality and bleak prospects. This includes many immigrants who originally came to Germany, attracted by the image of a strong economy and stable prosperity, as shown by a survey published this month. Among first-generation immigrants, 34 per cent wish to leave, and among their children, the figure rises to 37 per cent

Of course, far fewer native Germans want to emigrate — only 17 per cent. Yet, due to demographic challenges, Germany relies heavily on immigration. Migrants and the children of recent immigrants now make up roughly 30 per cent of the population — the youngest and most dynamic segment. Among them are families with children and numerous skilled professionals whom Germany previously recruited for free from less wealthy countries that educated them.

According to surveys, every second respondent says they want to emigrate in hope of a better life. Notably, because the surveys were conducted five times among the same group of respondents, it emerged that the share of those wishing to emigrate among migrants and their descendants rose by as much as 10% in the context of last year’s parliamentary elections. In other words, people are losing faith in the possibility of change, witnessing the endless shuffle of the same political parties and the apparent impossibility of real reform.

Current figures, which show that more than a third of migrants and their descendants want to leave the country they once eagerly sought to move to, also indicate long-term trends. Last summer, a similar study recorded that one in four migrants or their children were willing to emigrate. Pro-government German media attempt to downplay the situation, noting that only 2 per cent have concrete emigration plans for the coming year. Yet the fact remains that, according to official data, 1.2 million people actually left Germany in 2024 — the most recent year for which final statistics are available.

In conclusion, it is worth noting that fundamental economic problems exist only in the European Union. The current tough stance of the U.S. leadership—setting aside any sentiment and demanding ever more resources and privileges for American businesses—is not merely a whim of Trump. Although U.S. GDP is reportedly growing almost continuously, Americans actually have fewer financial and economic resources. The White House now has to extract money and resources from its allies with little subtlety, which explains the demands and ultimatums regarding the purchase of American goods.

Even this is not enough, and the U.S. government has to rely increasingly on debt. Interest payments on the federal debt have reached a historic high of $1.47 trillion per year. Federal interest payments rose 5 per cent compared to the previous year, to $1.2 trillion, and have doubled over the past four years. However, as an increasingly contested but still global hegemon, the U.S. has a unique source of funding its debt — the dollar, the world’s primary reserve currency.

This system is already beginning to show cracks, as seen in rising dollar inflation, the anxious reactions of the Washington establishment to de-dollarisation, and the global hegemon’s growing reliance on forceful measures to secure key resources.

Yet these dramatic operations and ostentatious reactions are becoming increasingly ineffective. A case in point is the U.S. government’s attempts to address dependence on its global competitor, China, in critical rare earth elements.

The 2019 deal with the Taliban, which included this component, ended only with the collapse of the pro-American regime in Kabul. There are suspicions that last year’s even more controversial rare earth deal with Ukraine may prove no more successful, as indicated by the current state of the peace process.

This trend is even more visible in the U.S.’s recent willingness to negotiate with China, despite bellicose rhetoric. For example, just this week, a key U.S. ally, the United Kingdom, quietly but significantly conceded to Beijing by allowing the Chinese to open a “mega-embassy” in London. After all, unlike the liberal regimes of the West, China is not just growing its GDP — it is expanding its real economy, reshaping the entire global balance of power.