Transatlantic relations through lens of US–Russia pendulum “Moment of truth” for Western alliance

The increasingly pronounced swings in the U.S.–Russia dialogue cast an equally pronounced shadow on transatlantic relations. This shadow intensifies the sense of a “moment of truth for the Western alliance.” Within it, new factors intertwine with long-standing constants in the United States’ relations with its European allies.

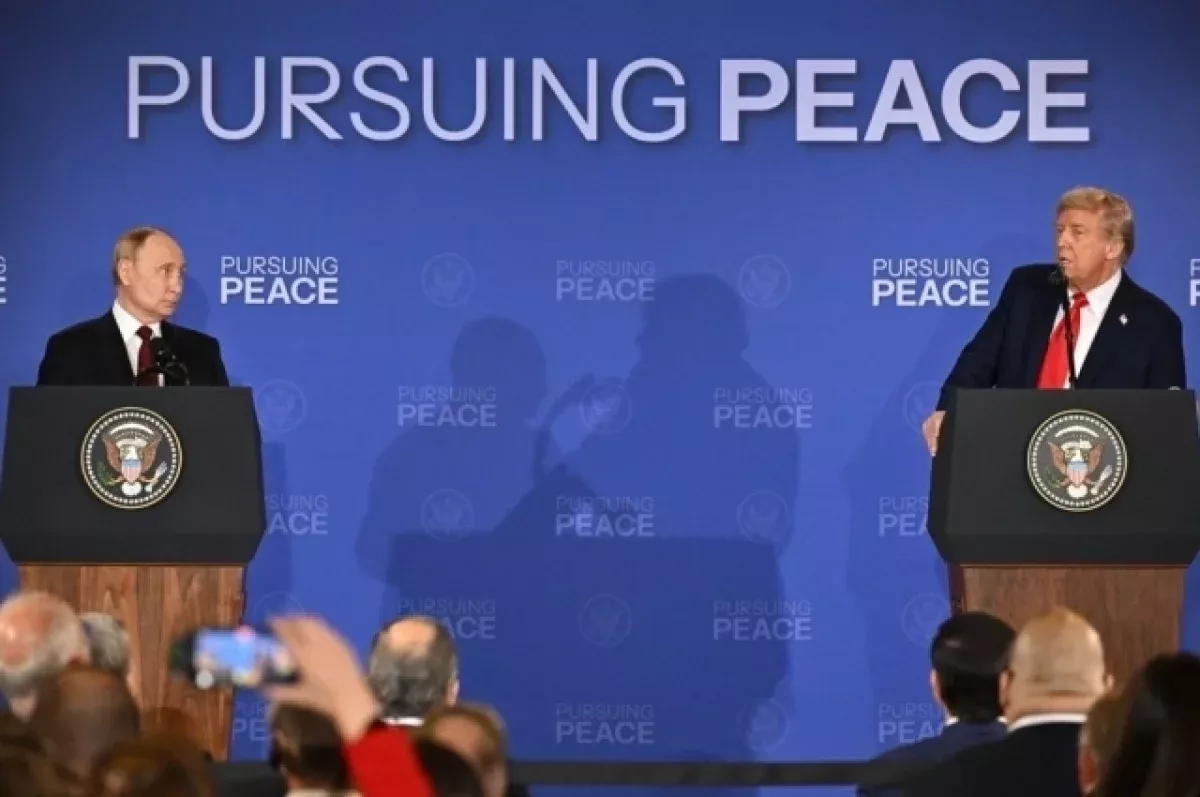

Over the past week and a half, with only a six-day interval, the “pendulum” in the Washington–Moscow dialogue reached two extreme points of amplitude. On October 16, global media almost treated it as a sensation when reports suddenly emerged about plans to organise a new U.S.–Russia summit in Budapest. By October 22, however, the U.S. not only halted preparations for the summit but also imposed sanctions on Russia’s two largest oil companies—a move perceived in Russia as deliberately hostile.

Such an amplitude of extremes invites reflection on several issues. First and foremost, of course, on the dynamics and prospects of U.S.–Russia relations themselves; on the possible scenarios for the further development of the Russia–Ukraine war; and, in a broader sense, on the confrontation along the Russia–West axis. It also raises questions about the foreign policy approach of the Donald Trump administration—its understanding of the “carrot and stick” in negotiations, and the logic of using both tools to achieve tactical and long-term objectives.

This amplitude also provides a useful snapshot for analysing transatlantic relations—that is, the relations between Washington and European capitals. European actors are actively trying to influence the U.S.–Russia dialogue and the decisions made by the Trump administration within this context. This is hardly surprising, since such decisions have direct consequences for most European countries, including their future cooperation with the United States.

“A stark moment of truth for the Western alliance”

Even after the controversial meeting between Volodymyr Zelenskyy and Donald Trump in the Oval Office on February 28 of this year, former chairman of the Munich Security Conference Wolfgang Ischinger wrote that the event reflected “a stark moment of truth for the Western alliance.” It is hard to disagree with that assessment.

In truth, the moment of truth for transatlantic relations may have arrived even earlier. Its timeline can be interpreted in various ways. At the very least, the extremely tough speech delivered by U.S. Vice President J.D. Vance to the Munich Security Conference—just two weeks before the Oval Office scandal—clearly indicated a transatlantic crisis. As we noted at the time, it marked a historic turning point in Washington’s relations with its European allies and signalled the emergence of a new “collective West.”

Regardless of the starting point, it is evident that the entire trajectory of the Russia–Ukraine war and the policies of the current U.S. administration in this context directly affect transatlantic relations. In this sense, everything that has happened over the past eight months—the swings in amplitude of the Moscow–Washington dialogue and all U.S. efforts to advance the peace process—continues to illuminate “a stark moment of truth for the Western alliance.” As Ischinger emphasised, these developments truly “called into question some of the bedrock assumptions that have undergirded the transatlantic relationship since World War II.”

Compared with February and March, when both sides of the Atlantic were still coming to terms with the idea that Donald Trump had returned to the White House, there has been a widespread adaptation to this reality. Likewise, the observation that “huge chasm has opened in transatlantic trust” and that they are “potentially catastrophic for transatlantic cohesion and the vitality of NATO” now sounds more matter-of-fact.

Nevertheless, every time the U.S. president announces that his latest phone call with his Russian counterpart went well, the level of anxiety in European capitals noticeably rises. News of planned in-person meetings produces even more intense shockwaves, reverberating through many of Europe’s most secure government buildings. NATO allies often learn about such news either from the media or only shortly before its publication—and certainly not through prior consultations with Washington, which would traditionally be considered standard practice among allies.

A similar shock occurred in August, when European leaders suddenly learned about Trump and Putin’s decision to meet in Alaska. Comparable waves swept across the continent after the announcement of plans to organise the next U.S.–Russia summit in Budapest.

Indeed, following both the Anchorage summit and just a few days after the announcement about Budapest, almost the opposite emotions swept through most European governments. As Trump’s tone toward Russia shifted, the sense of shock—and even humiliation—across Europe gave way to relief and satisfaction. In other words, the pendulum swings continued.

When it comes to the “moment of truth for the Western alliance,” what matters is not the emotional reaction of European leaders to each piece of news from U.S.–Russia talks. What matters is the clear fact that the European factor plays a largely secondary role in these negotiations, even though the topics being discussed primarily concern Europe and the interests of its states. Representatives of the European Union or individual European countries are not only excluded from the negotiation process, despite having insisted on participation from the outset, but in some cases Washington does not even manage to inform NATO allies of decisions already made—clearly seeing little practical significance in doing so. It is hard to imagine anything like this under the Biden administration—or under any U.S. president over the past several decades, with the exception of Trump himself.

Not all elements of the allied symphony are harmonising anymore

But do these swings in U.S.–Russia relations—and their shadow over Europe—signal a fundamentally new reality in transatlantic relations? Do they indicate that Washington’s European allies now face geopolitical conditions that never existed before? The answer is both yes and no.

It is clear that this new situation in transatlantic relations reflects, not least, the distinctive style of the current U.S. administration. Donald Trump’s first presidential term demonstrated that, both in election campaigns and as head of state, he does not feel bound by protocol, accepted norms of political correctness, or established practices of international engagement. Apparently, he expects the same from members of his cabinet. This approach applies equally to dealings with foreign opponents and with allies—and certainly extends to Europe, toward which the 45th and 47th U.S. president has long shown little affection.

Yet it would be a mistake to attribute everything solely to the style of the current White House occupant. It is evident that the new dynamics in U.S.–NATO relations cannot be reduced merely to Trump’s personal eccentricities or preferences, or those of his team. Once again, the key driving factor is the changing strategic significance of the European continent for U.S. calculations. This shift is not a matter of Trump or the foreign policy views of different Republican factions. Rather, it reflects the objective process of intensifying geopolitical confrontation between the U.S. and China, and the structuring of the entire international system around it.

To a large extent, this is what explains the new shadow that the U.S.–Russia negotiation swings cast over transatlantic relations.

The U.S. is indeed ceasing to be a “European power” in the sense that high-ranking American diplomat Richard Holbrooke understood the term in the mid-1990s. At the very least, it is no longer in the way that reflected the centrality of the European continent to U.S. national interests from the mid-20th century onward.

It is therefore unsurprising that unity between allies on both sides of the Atlantic is increasingly fraying—both in terms of worldview and the foreign and security policy objectives derived from it, as well as in the normative conception of the West’s civilizational mission. Missionary ideals remain deeply embedded in the DNA of both Europe and North America. Yet in day-to-day politics, under the banners of Trumpism and amid intensifying global geopolitical competition, they have become purely instrumental for Washington. What comes first are tangible American interests and the firm pursuit of those interests by any means necessary and with minimal cost.

Against this backdrop, the Trump administration does not even attempt the slightest pretense that the opinions and interests of European allies matter to Washington—whether in the context of negotiations with Russia or on any other issue. This is certainly not the image of transatlantic unity that former U.S. Secretary of State Dean Acheson described in the early 1960s. At the time, he likened allied policy to an orchestral performance, in which many instruments “weave together all the elements of a symphony.”

The core characteristic of transatlantic relations remains unchanged

Unsurprisingly, this has led European politicians to question the reliability of the U.S. as a key ally and security guarantor. Diplomats and experts across Europe now frequently note that trust in transatlantic relations has never been as pressing or as fraught as it is today.

At the same time, it seems that in Washington itself, there is little concern about this. Of course, some politicians and members of the expert community—particularly those close to the Democratic Party—continue to insist that the principal source of U.S. global power is its uniquely extensive and synergistic network of alliances.

NATO has always been the central element in this network. For this reason, they view the current administration’s harsh and openly dismissive attitude toward European allies as deeply mistaken and harmful to long-term U.S. interests. They hope that after Trump’s presidential term, the next U.S. leader will once again reach out to NATO allies and promise a renewed commitment to Europe.

However, first and foremost, the world has already changed—and will continue to change. These shifts define U.S. needs and interests in Europe. It is quite possible that the next White House occupant, even if a Democrat, will be grateful to Trump for the painful and unpopular adjustments in transatlantic relations, even if publicly Democratic representatives continue to criticise Republicans for their rough treatment of European allies.

Second, despite all the global shifts in the international system, the main characteristic of relations within NATO remains unchanged. Europe continues to be as dependent on the U.S. as it has been over the past seven decades. This does not mean that Europe has played no role in international politics during this period—it clearly has, and continues to do so. Yet at some point, both Europeans themselves and some outside observers developed the misleading impression that the continent’s global influence was far greater than its actual geopolitical capacity allowed.

The first signs of a renewed power-driven approach quickly reminded everyone that, without independent military strength, it is difficult to claim the status of a superpower. And that, by definition, there cannot be—and has never been—two equal actors in transatlantic relations.

Hypothetically, the EU has had the potential to take significant steps toward what is called “strategic autonomy.” But achieving this would have required not only political will, leadership, and decision-making grounded in it, but also overcoming numerous structural challenges and contradictions—both across the Atlantic and within Europe itself. Even in retrospect, it is difficult to imagine that recent history could have unfolded differently to make the scenario of strategic autonomy a realistic possibility.

Purely hypothetically, the ability to steer Europe’s political course toward strategic autonomy still exists today. Moreover, given Washington’s increasingly hardline stance toward its European allies, the likelihood of such a scenario may even be higher. Yet this remains highly theoretical. In practical terms, it is still difficult to envision how the diverse polyphony of perspectives and interests across European capitals could overcome the same structural challenges and contradictions—especially under conditions of pervasive uncertainty.