Why does France need a penal colony in Guiana? Prison of the future with a stench from the past

Paris plans to reinstate a high-security prison in French Guiana. Residents of the overseas department are outraged by what they see as a new relapse into colonialism.

The penal colony in French Guiana was first established by Emperor Napoleon III—for political opponents and especially dangerous criminals. So why is the current President of France, in what is supposedly an era of democracy and human rights, emulating Bonaparte?

The Devil’s Colony

On May 17, during an official visit to French Guiana, Justice Minister Gérald Darmanin announced that a special block for drug traffickers and Islamic militants would be included in the prison facility currently under construction in the territory.

These plans have sparked strong dissatisfaction among the residents of the overseas department. The decision to build the prison in the town of Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni was made back in 2017. The cost of the new 500-inmate penitentiary facility is estimated at $450 million. Construction is expected to be completed by 2028.

Originally, the facility was intended exclusively for local inmates—the old prison has long been overcrowded. However, the announcement that high-risk criminals from mainland France would be transferred here has evoked associations with the darkest days of colonialism.

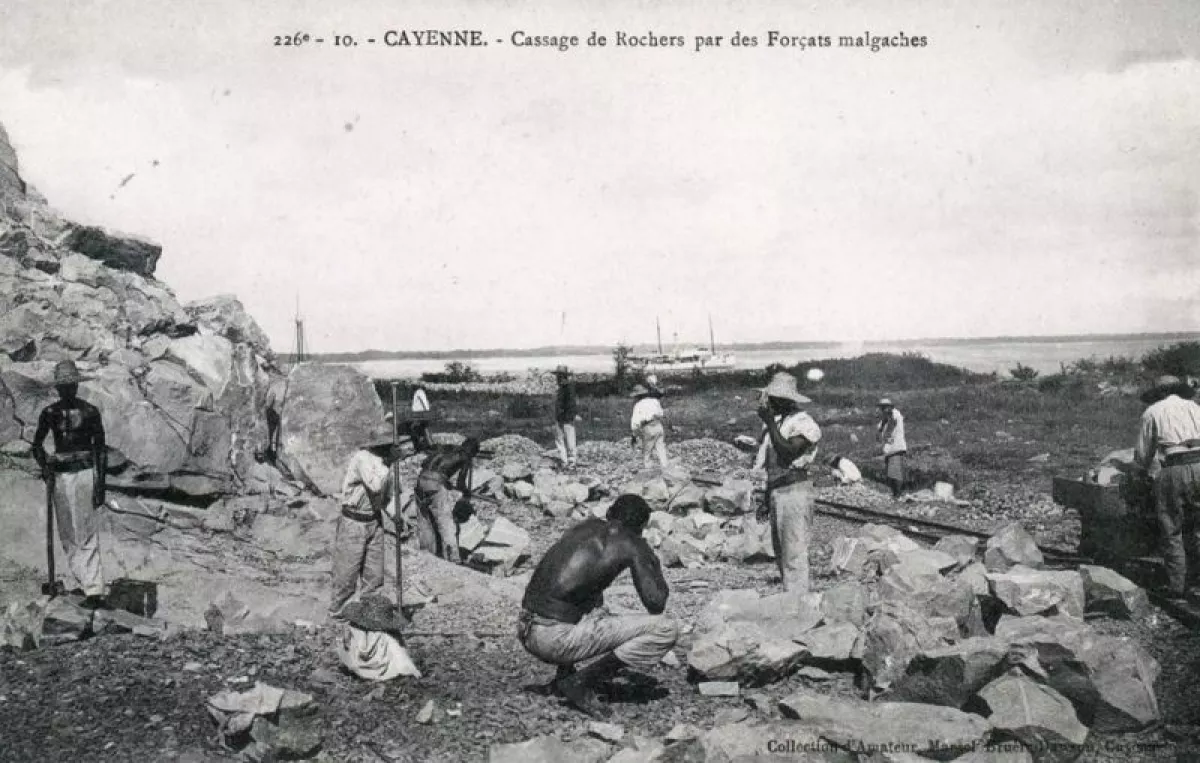

In the past, forced prison labour played a key role in developing the French colony. The French established a plantation economy, but the local population refused to work for the colonisers. As a result, African slaves were brought in. After the abolition of slavery in 1848, convict labour became its replacement.

In 1852, Napoleon III issued a decree ordering the deportation of convicts from France to Guiana. Prisons were built in Cayenne and on Devil’s Island. In 1858, a leper colony in Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni was converted into a prison—lepers were replaced by convicts. The town became the administrative centre of the penal colony.

Prisoners served two sentences: first, their official prison term, and then an equal period in forced settlement—often for life.

Exhausting labour, meagre rations, malaria, dengue fever, and the chikungunya virus claimed the lives of up to 40% of European inmates within the first year. Work in the swampy jungles—teeming with snakes and crocodiles—completed the grim picture.

The phrase "dry guillotine" was coined specifically for such penal settlements. There was also a "wet" version: for repeat offenders, prisoners were beheaded on the spot.

In 1867, Europeans stopped being sent to Guiana due to the high death rate—the penal colony was relocated to New Caledonia. But in 1887, it was shut down as "too soft," and France returned to Cayenne once again.

The harshest place was known as "Devil’s Island" (Île du Diable), a tropical "paradise" located 13 km off the coast. Up to 97% of prisoners died there. It is said that around 50,000 people perished on the island. Bodies were thrown into the sea—fed to sharks. The solitary cells, measuring just 3 square metres with tattered canvas instead of roofs, turned alternately into ovens or pools. Insects, filth, beatings, and starvation were all routine. Food was given only once every 2-3 days.

The average life expectancy on the island was five years. Political prisoners were sent there. After Napoleon III’s coup in 1851, 231 republicans were imprisoned there. Later, anarchists, deserters, and pacifists from the First World War were also held. One of the few escapees, Clément Duval, described the horrors of the penal colony in his book.

The penal colony was officially closed only in 1953, after Guiana became an overseas department of France.

Colonial regression

The news about the creation of a special high-security block is therefore perceived today as a step backwards to the era of colonial violence. The decision was made without consulting the authorities of Guiana. Acting president of the regional assembly, Jean-Paul Ferreira, said that the deputies were “stunned” — no one had discussed the plans with them. He called it disrespectful and insulting.

Local residents also expressed outrage. The region already suffers from high crime rates, and no one wants the “import” of criminal bosses and radicals from the mainland. Even isolated within the special block, they would become a magnet for local gangs.

Deputy Jean-Victor Castor sent a letter to the Prime Minister demanding the project be abandoned: “This is an insult to our history, a political provocation, and colonial regression.”

Political crisis and the ghosts of Devil’s Island

Why are Macron and his government returning to the methods of the old colonial school? Darmanin explains it as a fight against drug trafficking and the need to isolate drug cartel leaders from their accomplices: “My strategy is simple — to strike organised crime at all levels.”

It is worth noting that Minister Darmanin himself has twice been involved in cases related to sexual misconduct.

Darmanin spoke about the construction of three special prisons as early as January, but did not disclose their locations. The first, designed to hold 100 drug cartel leaders, is scheduled to open in July 2025.

Unions have opposed the plan, stating that concentrating dangerous criminals in one place increases risks, including for the staff. Such practices have not proven successful in South America.

France abandoned special prison regimes back in the 1980s. Today, experts consider their revival a violation of the European Convention on Human Rights and several UN treaties.

However, the situation in French prisons has indeed worsened. In April, the country saw a wave of attacks on prisons and security guard residences — involving automatic weapons and Molotov cocktails. Up to 65 attacks were recorded. Responsibility was claimed by the group “Defence of the Rights of French Prisoners” (DDPF), allegedly linked to the Marseille-based DZ Mafia. The attacks are connected to the new anti-drug law.

DDPF stated: “The goal is to condemn Vinci and other companies profiting from building prisons where people are subjected to cruel treatment.”

French prisons are overcrowded. The government is constructing new assembly-style prisons with 3,000 places and plans to deport a thousand Romanian convicts to serve their sentences in their home country.

Yet Darmanin’s motives raise questions. He himself acknowledges that Guiana is a starting point for drug trafficking. So how exactly is a special prison in this region supposed to isolate criminals from their networks?

In France, security services are already struggling to control criminal networks within the country. What makes anyone think they’ll fare better in Guiana — a region plagued by rampant crime and a murder rate of 20 per 100,000 people, 14 times higher than the national average?

All signs suggest that the special prison’s purpose goes beyond fighting the drug trade. The fact that some spaces are reserved for Islamic radicals points to a political dimension. Today it’s Islamists — tomorrow it could be any dissenters easily branded as extremists.

This approach is already being employed in some EU countries. France is facing not only a socio-economic but also a deepening political crisis. President Macron has once again failed to secure a parliamentary majority, and radical movements are gaining momentum.

Justice Minister Darmanin, a member of the right-wing conservative party Les Républicains, has previously taken part in rallies backed by the far right. Against this backdrop, France is undergoing increasing militarisation, while Macron himself seems drawn to military adventures abroad.

If the crisis intensifies, special prisons in overseas territories could become tools to silence dissent. Paris has plenty of experience in this — and, it seems, little hesitation in repeating it.