Saudi prince in Washington: bargaining over the new world order Pragmatism replaces ideology

The U.S., along with other Western countries, is reevaluating its approach to relations with allies and partners, abandoning many of its previous demands. A recent example this week was the visit of Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince to the United States. For a long time, the Western establishment—especially the global liberal elites—tried to make him an outcast. But the geopolitical context and the global balance of power have shifted—and now the entire ideologically charged rhetoric of the collective West dissipates like smoke. Pragmatic negotiations begin.

This current shift of historical eras, associated with the world moving toward a more multipolar structure, lacks drama and romantic imagery. Global powers, faced with the rise of non-Western countries, are trying to share their influence and hegemony with their allies. If they do not share it, their hegemony’s days are numbered, as it is becoming increasingly difficult for former world powers to maintain it alone.

Return to Washington

For many years, the global liberal establishment, particularly the former Democratic leadership in the U.S., kept Saudi Arabia’s Prime Minister and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman at arm’s length.

Among the most dramatic accusations against him was the claim that he was responsible for the killing of journalist Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul.

Without delving into the technicalities of this accusation, it suffices to note how colorfully it was voiced by U.S. Democrats, whose leaders, like Hillary Clinton, openly celebrated the torture, rape, and brutal killing of the Libyan leader on television—a consequence of their own policies. We need not even recall their complicity in the more anonymous mass crimes worldwide resulting from invasions, occupations, and sanctions. These politicians had no moral authority to judge others. In Khashoggi’s case, their concern was mainly because he was a highly effective executor of the liberal establishment’s will in pressuring Saudi Arabia.

This was Mohammed bin Salman’s first visit to the U.S. since Khashoggi’s murder in 2018. President Trump simply set aside the liberal accusations and formally welcomed the Saudi heir: cavalry escort, military band, artillery salute, and a flyover by fighter jets—all signalling the U.S. leadership’s stance. The talks, though filled with grandiose statements, resulted in the signing of breakthrough agreements for Riyadh’s international position and the nature of Saudi-American relations.

The agreements included a joint declaration concluding negotiations on civil nuclear energy cooperation, a framework for uranium, magnets, and critical minerals supply, and a memorandum of understanding in artificial intelligence.

Elon Musk, returning to the White House after prior disagreements with Trump, announced that his company xAI would, together with Saudi Arabia and Nvidia, launch a “500 MW project,” building a data center in the Kingdom of this capacity. Saudi funds would also support previously announced plans to attract an additional $15 billion in investments and raise xAI’s capitalization to $230 billion—more than double its valuation at the start of the year. Overall, Saudi Arabia pledged to increase its investment commitments to the U.S. to $1 trillion—nearly doubling the amount promised during Trump’s Middle East tour in May. Currently, the U.S. government is actively seeking such investments and any capital worldwide, including selling migration rights in exchange for investment, reflecting the West’s pressing needs.

Is the US ceding positions to allies to keep them out of enemy hands?

Even more striking were the Saudi-American agreements in the military sphere, including a strategic defence pact and discussions on potential F-35 fighter jets and Abrams tanks deliveries. Trump emphasised that Saudi Arabia’s air force should be no less capable than that of the U.S.’s long-standing key regional ally, Israel. Previously, Washington had never been in a hurry to provide such systems to Israel.

For decades, the U.S. supplied Israel with this equipment mainly through the persistent efforts of the Israeli government and lobbying channels within U.S. politics. That Trump agreed to provide the same to Saudi Arabia—whose lobbying capabilities are incomparable to Israel’s—speaks volumes about changing eras.

Additionally, the U.S. granted Saudi Arabia the status of a major non-NATO ally, a designation held by roughly two dozen countries worldwide, offering advantages in purchasing U.S. weapons and simplifying procurement by bypassing Congressional approval. While other Arab states have held this status, financial constraints or small size limited their practical benefit. Saudi Arabia, a large country seeking regional power, is a different case. Washington’s decision effectively delegates Riyadh the role of maintaining a U.S.-acceptable balance of power in the region without massive U.S. involvement.

No substitute for each other: the US, China, and Russia

Yet Riyadh did not pay a heavy price for these strategic agreements. Regarding investments, despite the huge pledged sum, no detailed plans or programs were specified, leaving the money under Saudi control and preserving room for further negotiation. On foreign policy, Riyadh maintains its longstanding approach. Without abandoning contacts with Israel, it hinted that it would not rush to join the so-called Abraham Accords. As bin Salman stated, “We want also to be sure that we secure a clear path of two-state solution [i.e., Palestine and Israel].”

Moreover, bin Salman attempted to mediate between Iran and the U.S., having received a message from Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian before his visit. This effort succeeded, as Trump stated: “I am fully open to this, and we are talking with them. We are starting the process. But it would be good to reach a deal with Iran.” Saudi Arabia thus secured a significant role in shaping U.S. regional alliances, a role it chose for itself rather than one imposed by the U.S.

Most importantly, and ignored by liberal media, Saudi Arabia did not sever relations with Russia or China. Relations with Russia have remained solid in recent years, and ties with China are even stronger. During the worst period of Saudi-American relations, Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Saudi Arabia in 2022. On Chinese guarantees, the 2023 regional deal between Saudi Arabia and Iran—ending long-standing destructive rivalry—was brokered, becoming a cornerstone of the Gulf’s international architecture and strengthening China’s regional position, as evidenced by regular contacts.

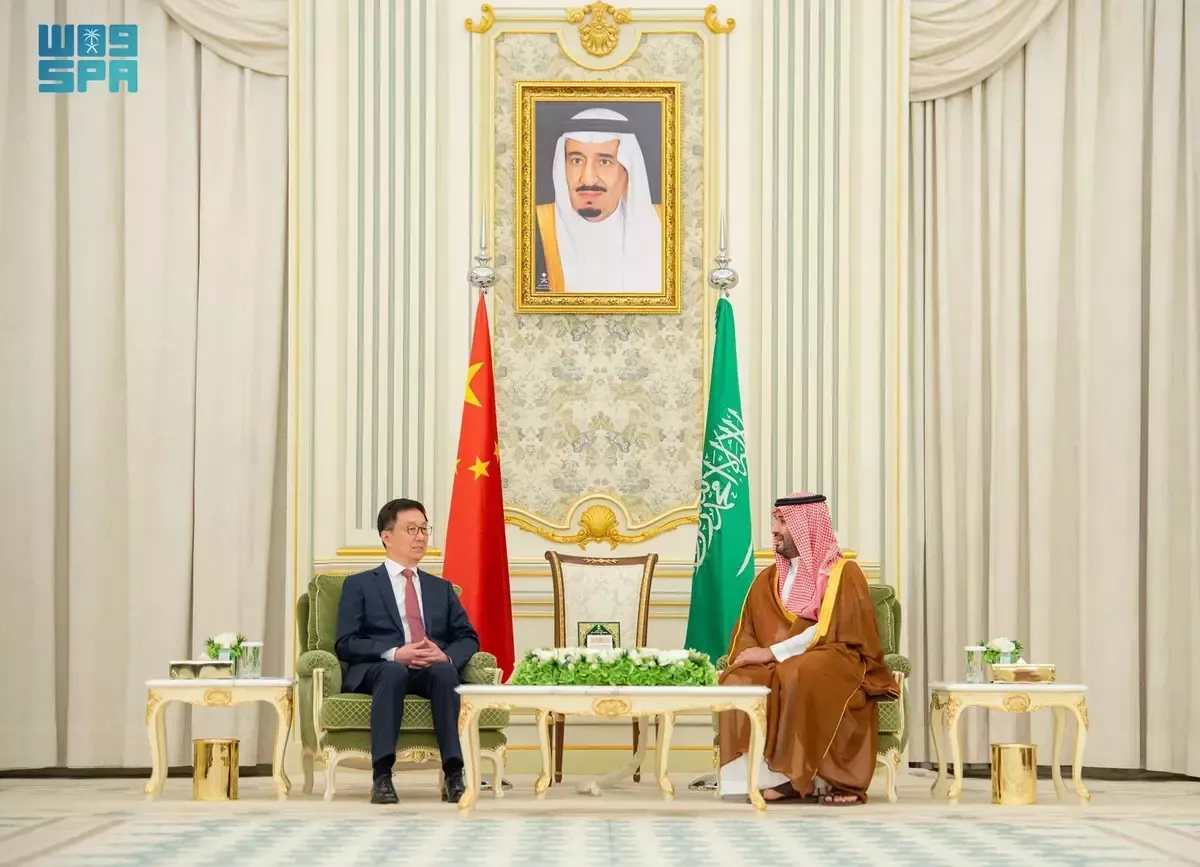

On October 29, Chinese Vice Premier Han Zheng met with Mohammed bin Salman in Riyadh, reiterating that “Saudi Arabia is a comprehensive strategic partner of China, and Beijing has always prioritised Riyadh in its diplomacy.” Bin Salman emphasised that “the two countries are good friends and partners; political relations are strong and at the highest level,” supported by similar positions on regional and global issues. Moreover, “Saudi Arabia is ready to deepen cooperation with China in areas such as economy and trade, investment, artificial intelligence, renewable energy, and mining, to achieve common development.” Comparing this to the Saudi-American agreements, the list of topics is strikingly similar.

Riyadh is not choosing between global rivals—it simply builds relations with all. This is not only possible but also creates better conditions for development. While seemingly obvious, Western elites have long insisted that Eastern European countries make a “civilizational choice,” sacrificing economic benefits, severing ties, and even creating enmity between partners. They followed this path, unlike Saudi Arabia, with clear consequences.

The example of Saudi Arabia, Central Asian countries, and Azerbaijan shows that a balanced, sovereign approach yields more than subservience—even in the ruthless world of imperial politics. It is not about one country alone; Washington is reassessing its relations with many countries in this manner. This was evident at the recent U.S.-Central Asia summit, where nations long criticised for human rights violations received a more pragmatic approach.

The contrast between the calm, confident behaviour of Saudi (and other non-Western) leaders and European leaders is striking. In early November, EU and major European leaders avoided attending a summit they themselves convened with Latin American countries, fearing they might anger Donald Trump by interacting with nations in the U.S.’s near abroad. Despite months of efforts to please him, they hesitated. The decline of the collective West and the rise of the rest of the world are reflected in these psychological reactions as much as in economic statistics.