Soviet-era territorial claimants and their ruined hopes Aganbegyan, Balayan in the shadow of new realities in South Caucasus

As is known, in his address on August 23, 2025, on the occasion of the anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence—which asserts territorial claims against Azerbaijan and is one of the documents upon which the Armenian constitution relies—Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan made several rather interesting points. First and foremost, he described the ideological provisions of the declaration as conflictual, since they reflected “that model of collective patriotism” which the Soviet Union had systematically instilled in Armenian society from the 1950s onward. Pashinyan identified the creation of a socio-psychological environment in Armenian society—through literature and art aimed at undermining this ideology—as a means to cultivate a deep awareness of the “strategic impossibility of the existence of an independent Armenian state, since a country surrounded by a constant context of conflict cannot build genuine independence.”

According to the Prime Minister, this reality led him to the conviction that Armenia should abandon the continuation of the “Karabakh movement” in order not to jeopardise the country’s independence. In Pashinyan’s clarification, given his strategy of making independence a reality, establishing peace between Armenia and Azerbaijan became possible, similarly to normalising relations with Türkiye. As the head of the Armenian government summarised, August 2025 “marked the beginning of a peaceful and prosperous life for Armenia.”

It should be recalled that earlier this month in Washington, during the trilateral Azerbaijan–Armenia–U.S. meeting, the notorious OSCE Minsk Group was effectively buried. At the same time, Baku and Yerevan initialled a previously agreed text of a peace treaty, which includes all the principles voiced by Baku, including the opening of regional communications, in particular ensuring unobstructed connectivity between the main part of our country and the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic. President Ilham Aliyev emphasised that the final signing of the peace treaty would be possible only if amendments were made to the Armenian Constitution, which currently preserves aggressive aspirations toward Azerbaijan due to its reliance on that very declaration.

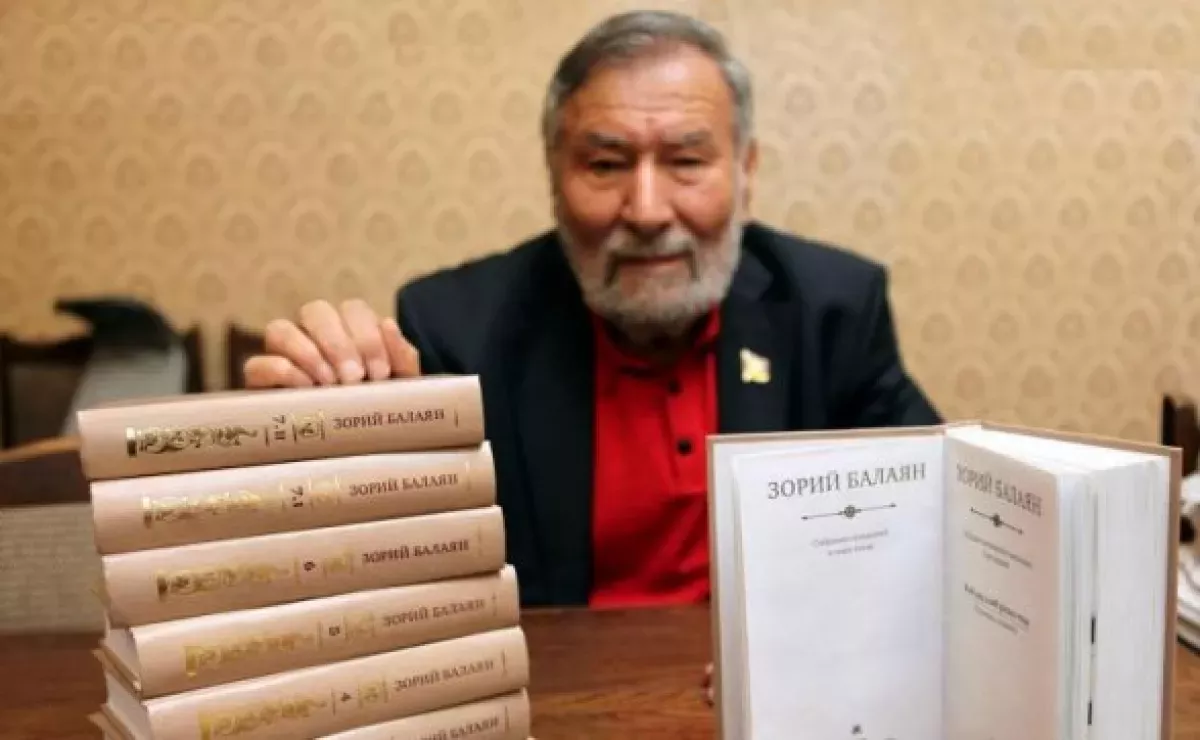

We draw attention to these facts due to our interest in how two individuals, who were directly involved in fomenting territorial claims against historically Azerbaijani lands back in Soviet Armenia—Zori Balayan and Abel Aganbegyan—responded to the latest developments. After all, since November 2020, they seem to have remained completely silent.

As we recall, academician Abel Aganbegyan—economic advisor to the last General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev—stated in November 1987 in an interview with the French newspaper L’Humanité: “As an economist, I believe that [Karabakh] is more connected to Armenia than to Azerbaijan.”

Meanwhile, Zori Balayan is the author of a manifesto of hatred, racism, fascism, and anti-humanism of the Soviet era, entitled Ochak. Balayan once recalled that on February 17, 1988, while part of a Soviet delegation in the United States, in his speech at the UN before representatives of over 30 countries, he “drew their attention to the fact that almost no one knows what kind of state Karabakh is, or where it is located.” In every city visited by the delegation, Balayan “talked about his Artsakh,” but everywhere he was met with the response: “I’m hearing about it for the first time.”

The following day, in a speech at the CPSU Central Committee plenum, Gorbachev emphasised the increased role of the Soviets as a structure for implementing the “democratic principles of socialism.” This striking coincidence between the statements of Balayan and Gorbachev resulted in the session of the Council of People’s Deputies of the then NKAO speaking out on February 20, adopting a decision to request the Supreme Soviets of Azerbaijan, Armenia, and the USSR to “resolve the question of transferring the NKAO from the Azerbaijan SSR to the Armenian SSR.”

According to Balayan’s recollections, a day later, while departing from New York to Moscow, he met Aganbegyan at the airport, who, when asked, “So, what’s happening in the Union?” joyfully replied: “You know, everyone is talking about Karabakh.”

In this way, these two individuals helped fuel anti-Azerbaijani hysteria in Armenia—and across the entire Soviet Union—continuing this agenda in the years that followed. For instance, in 1990, Balayan described the then NKAO as “a Christian island surrounded by seven million Muslims” and added that, for him, “Karabakh is Armenia.” He went on to declare that “we will never be at peace until Western Armenia” (i.e., the territory located in Türkiye—ed. note) “has its issue resolved.”

In this context, it is quite telling that Viktor Krivopuskov, head of the investigative-operational group of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs in Karabakh in 1990–1991—infamously mingling in saunas with separatists—praised Balayan, describing him as “the ruler of millions of reading souls, hundreds of thousands of demonstrators, the entire Armenian people,” who had become “a unifying figure for the reunification of Karabakh with Armenia, its independence and state revival, the inviolability of Christian unity, and friendship with Russia.”

After the collapse of the USSR, in an open letter to then-Russian President Boris Yeltsin, Balayan emphasised that “right now, as Russia stands at a crossroads in choosing a path to real salvation, Christian Karabakh will continue its struggle for survival as part of historical Armenia, which has become part of Russia as a reliable outpost.”

Balayan continued to use the format of open letters during Vladimir Putin’s presidency. In a letter addressed to him in 2013, Balayan reiterated the thesis that “there is no Karabakh problem—there is a problem of Russia.”

Balayan made his presence felt again in 2019, describing the unresolved nature of the conflict “at the political-diplomatic level for more than twenty-five years” as a result of the “aggressive behavior of official Baku.”

However, it must be noted that since November 2020, neither Balayan nor Aganbegyan has been heard from. They have not uttered a single word regarding Azerbaijan’s restoration of historical justice. This raises the question: did Balayan perhaps foresee this outcome, understanding that sooner or later the Azerbaijani people’s Liberation War to de-occupy their historical lands would lead to the natural conclusion? Or, on the contrary, did he never even in his worst nightmares anticipate such a turn of events?

Well, we hope that both Zori Balayan and Abel Aganbegyan are of sound mind and fully understand the current—and future—South Caucasian realities recognised by the world. Whether their voices will be heard in this regard or not is, in fact, of little importance. What matters most is that they have witnessed the collapse of the “miatsum” and their own hopes, which couldn't have unfolded any differently.