Evolution of French colonialism: Unveiling legacy - Article one Corbin’s report

The core objective of France's colonial policy has consistently been, and remains, to extract the greatest possible benefits for the metropole. This is the central argument of the report The Evolution of French Colonialism: A Political and Constitutional Study by international governance expert Carlyle Corbin. This 108-page document offers valuable insights into the phases of emergence and development of France's oppression and exploitation of peoples living thousands of kilometres from Paris.

Given the current relevance and heightened interest in this subject, Caliber.Az has decided to publish a series of articles based on the preliminary data presented in Corbin's study. Each of the author's theses and conclusions is thoroughly verifiable. Corbin, originally from the Virgin Islands, has a firsthand understanding of the issues at hand. He specializes in both French and British colonial history, which effectively eliminates any concerns of bias.

So, what does Carlyle Corbin discuss in the first part of his report?

Origins of French colonialism

During the so-called "Age of Discovery," the French, along with the Spanish, Portuguese, English, and Dutch, established settlements and colonies in North and South America, the Caribbean, and ventured into the Asia-Pacific region and Africa. France's first colony, Acadia (now Nova Scotia, Canada), was founded in 1605, followed by the establishment of Quebec in 1608. Louisiana was founded in 1699. These and other territories claimed by France, which are now part of Canada and the United States, were known as New France. Historically, French colonies in North America lagged significantly behind British colonies in terms of population and economic development. Acadia was ceded to the British under the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, and Louisiana was sold to the United States in 1803.

The initial French invasion of North America in the early 17th century marked the beginning of the First French Colonial Empire. This imperial expansion also extended to the Caribbean, with territorial settlements established in 1624 on the northern coast of South America, now known as French Guiana. During this period, the eastern Caribbean islands of St. Kitts, Saint Lucia, and Dominica were also colonized, but were later lost to the British. Notably, the French ceded many of their colonies in North America and Asia to the British, which ultimately allowed these island nations to achieve full independence in the latter half of the 20th century.

The history of Guadeloupe and Martinique is equally dramatic. These islands were captured by France between 1635 and 1658. Historical accounts reveal that the French invasion of the Caribbean islands was driven by the growing demand for sugarcane in Europe. The first French settlers arrived on the islands as early as 1625, and by 1658, King Louis XIV asserted French claims over Martinique. The French invasion of Martinique faced strong resistance from the indigenous Kalinago people, who were eventually defeated. To solidify their presence on the islands, France sent a group of Jesuit missionaries with the goal of converting the indigenous people to the Roman Catholic Church. These events marked the beginning of a period of commercial dependence, during which the islands were managed by various French private companies with the support of the clergy.

Meanwhile, the indigenous people of Martinique continued to resist the occupation of their island, refusing to work on the sugar and cocoa plantations established on land stolen from them by the French trading class. As a result, King Louis XIV of France issued a collection of royal decrees in 1685, known as the "Code Noir" (Black Code), which legalized the use of African slaves in Martinique and other French Caribbean colonies.

In his book French Colonialism, Leonard Smith, a history professor at Oberlin College, noted that "the French West India Company sent two ships to the West African kingdom of Ardres (in today’s Benin) to establish a base for commerce, meaning primarily the trade in enslaved persons." Furthermore, the Code Noir became a tool of significant cruelty in the hands of some French colonists.

Thus, a transatlantic slave trade network was established, linking Africa and the Caribbean for the purpose of exploiting slaves on French plantations, accompanied by the forcible abduction of Africans from the continent. It was anticipated that sugar derived from cane would significantly transform the French Empire. By the 18th century, the Caribbean islands accounted for up to 20 per cent of France's external trade. According to Professor Smith, sugar, coffee, and bean plantations demonstrated French mercantilism in its most corrupt and, at the same time, most profitable form.

The French invasion of Martinique led to the forced relocation of the island's population to the leeward side, driven by the increasing number of French settlers seeking to claim the best lands. This intensified local dissatisfaction and led to an uprising that was eventually suppressed, resulting in the expulsion of the indigenous Martinicans and the beginning of ethnic cleansing. Many Kalinago were killed, and those who survived were driven off the island.

The most significant colonial acquisition for France in the Caribbean was the colony of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), established in 1664. By the 18th century, Saint-Domingue had become the wealthiest sugar colony in the Caribbean, remaining under French control until the Haitian Revolution of 1791-1804. The French Revolution of 1794 led to the abolition of slavery throughout France and its colonies, but political equality was still not achieved.

Alongside French colonial expansion in the Caribbean during the period of the First French Colonial Empire, incursions were also made into Asia and Africa. To this end, the French East India Company was founded in 1664 to compete in Eastern trade.

Colonies were established in Western Bengal (1673), throughout southern India, and on Indian Ocean islands such as Bourbon (Réunion, 1664), Mauritius (1718), and the Seychelles (1756). For over 350 years, the French expanded their control over Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. The French East India Company, a trading organization created to expand trade and promote Catholicism, established a presence in Indochina in 1668. France later consolidated its colonies in the region into a single entity known as French Indochina. Due to its geographic location and abundant natural resources, the colony became crucial for French geostrategic and geoeconomic interests in Southeast Asia.

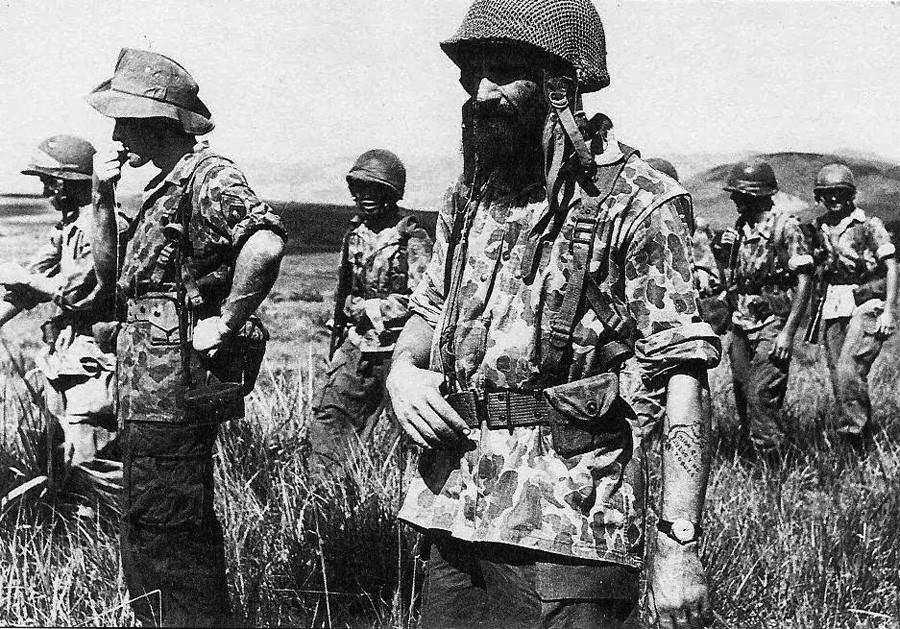

To further consolidate their colonial system, the French altered the social and economic landscape of French Indochina. Departments were established to oversee finances, customs and monopolies, public works, agriculture and trade, postal and telegraph services, and other institutions. Monopolies were implemented on opium, salt, and alcohol. Vietnam, in turn, produced rice, rubber, and coal. The French government in Indochina began exporting these goods and utilizing rural labour to increase production rates to keep up with demand. The oppression of the Vietnamese was particularly brutal, with any form of political dissent leading to severe repression. Books and newspapers deemed subversive were confiscated, and anti-colonial political activists were sentenced to death or long-term imprisonment.

Regarding French presence in Africa, it dates back to the 17th century, but the main period of colonial expansion occurred in the 19th century with the invasion of Algeria in 1830, conquests in West and Equatorial Africa during the so-called Scramble for Africa, and the establishment of protectorates in Tunisia and Morocco. By the end of World War I, French holdings in Africa were expanded to include parts of Togo and Cameroon. By 1930, French colonial Africa comprised extensive confederations of French West Africa and French Equatorial Africa, the western Maghreb, the island of Madagascar, the Comoros (including Mayotte), and Djibouti on the Horn of Africa. Territories south of the Sahara were viewed by Paris primarily as objects of exploitation, while the Maghreb region was targeted for settlement by European emigrants.

In the 19th century, France also seized part of Polynesia in the Pacific Ocean, now known as French Polynesia. The annexation of Polynesia followed the Franco-Tahitian War of 1844-1846 and the Leeward Islands War from 1888 to 1897. The 1880 annexation law established French laws as superior to local customs, resulting in significant changes to land ownership systems and the dispossession of many indigenous landowners.

French colonial rule left a profound impact on all aspects of life in the Pacific region, leading to a complex blending of traditional and colonial values. Colonial systems of administration, education, and religion infiltrated and began to dominate the lives of indigenous peoples. As a result, many indigenous languages were pushed to the brink of extinction.

The second part is available here.

By Samir Guliyev