Iran on the brink of uncertainty Anatomy of the protests and transformation scenarios

The protests sweeping through Tehran, Isfahan, Shiraz, and dozens of other Iranian cities began spontaneously after another increase in the prices of basic goods, but they quickly escalated into something much larger. What is happening today on the streets of Iranian cities differs from the unrest of 2009, 2017, 2019, and even the large-scale protests of 2022–2023 following the death of Mahsa Amini—not in scale or slogans, but in fatigue. Society is exhausted with the regime, exhausted with repression, exhausted with economic collapse.

On the surface, the scene looks familiar: women publicly remove their hijabs and burn them in the squares; bazaars close in solidarity; workers go on strike. Security forces deploy water cannons, tear gas, and live ammunition, the internet is shut down, and activists are arrested by the hundreds. But behind this apparent repetition lies a fundamental shift. Protesters are no longer putting forward reform demands or trying to negotiate with the authorities. They simply ignore the existence of the regime, living as if it does not exist. The system is losing not so much control as relevance.

The Iranian authorities understand the nature of the threat but do not know how to respond. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), which de facto controls the security apparatus and a huge portion of the economy, is facing a legitimacy crisis even within its own ranks. Young IRGC officers, many of whom were born after the 1979 revolution, do not share the ideological fanaticism of the older generation. They see corruption among the generals, the gap between rhetoric and reality, and how their own families are growing poorer. This does not mean the IRGC is ready to mutiny, but it does mean that its monolithic nature can no longer be taken for granted. The guards are still willing to fire on crowds, but the question is: for how long?

The religious establishment is undergoing its own existential crisis. A segment of the clergy in Qom understands that harshness is destroying not only the political system but also the authority of Islam in the eyes of Iranian society. Young Iranians are increasingly turning away from religion, associating it with repression and backwardness. Some clerics call for a softening of policies, dialogue with society, and reforms that would preserve at least a remnant of religious legitimacy. Others insist that any concessions would be perceived as weakness and would only hasten the collapse of the system.

Ali Khamenei, now 86, is increasingly unsteady in balancing these positions. His health has become the subject of constant speculation, and the question of succession has shifted from a theoretical problem to an urgent practical issue.

The economic situation makes the political crisis extremely difficult to resolve. Sanctions have turned the Iranian economy into a state of permanent survival. Inflation runs into double digits annually, the national currency has fallen to historic lows, and youth unemployment exceeds 40 per cent. The IRGC controls vast sectors of the economy through front companies, but this system serves only to enrich the generals.

The system is trying to use oil revenues to maintain the loyalty of key groups, but oil prices fluctuate, and export opportunities are limited by sanctions and the need to sell crude at significant discounts to China and other buyers willing to bypass international restrictions. Subsidies on food, fuel, and imports through preferential exchange rates account for a large share of the budget and fuel inflation, but any abrupt removal or reform immediately sparks protests. The authorities are trapped: maintaining subsidies inflates deficits and corruption, while removing them triggers sharp price hikes and social unrest.

The current protests began precisely after the removal of the preferential exchange rate (285,000 rials per dollar) for importing most basic goods (except medicines and wheat), which led to a sharp rise in prices—vegetable oil doubled, and the cost of chicken, eggs, cheese, and imported rice increased even more. Overall food prices rose by more than 70% over the year. For a family of four, this means that the monthly food budget, already consuming a large share of income with average wages ranging from $150–$250, has risen even further, pushing millions of households into a critical situation.

The international dimension of Iran’s crisis makes it particularly explosive at the start of 2026. The regional situation has changed radically over the past year and a half. Israel is on heightened alert, viewing the weakening of Iran as a historic opportunity to eliminate its main strategic threat.

Under the Trump administration, the United States has taken a stance that differs qualitatively from previous approaches. Trump returned to a policy of maximum pressure on Iran but added a new element: public threats of military intervention if the mass killings of protesters continue.

In a series of statements on Truth Social and at press conferences over the past two weeks, Trump signalled that Washington is considering strikes against Iran. He frames his statements around “protecting human rights” and “preventing genocide against one’s own people,” which, according to U.S. officials, creates a legal and moral basis for intervention. On January 2, he wrote on Truth Social: “If Iran shots [sic] and violently kills peaceful protesters, which is their custom, the United States of America will come to their rescue. We are locked and loaded and ready to go.”

Secretary of State Marco Rubio, on January 10 in a post on X, added: “The United States supports the brave people of Iran.”

In subsequent statements on January 11–12, Trump himself noted that Iran is “starting to cross the red line” and that the administration is considering “very strong response options,” including possible military measures if the repression continues. According to media leaks (WSJ, Reuters, NPR), discussions include strikes on IRGC infrastructure or key figures within the regime, as well as other tools such as cyberattacks and sanctions. Nevertheless, the death toll is already significant: according to HRANA (as of January 11–12), there are 490–544 confirmed protesters killed, plus dozens of security personnel (over 100 according to state media).

These statements by the Washington administration serve several purposes simultaneously. First, they warn the regime that mass shootings will have military consequences, creating a deterrent effect. Second, they provide moral support to the protesters, signalling that the world is not indifferent. Third, they establish a legal framework for a potential operation, which could be presented not as aggression but as a humanitarian intervention in the spirit of the “responsibility to protect” doctrine.

But behind all of this lies a complex calculation. Trump understands that direct military intervention carries unpredictable consequences. The experiences of Iraq and Afghanistan have not gone away, and American society is weary of Middle Eastern wars. Republicans in Congress, while supporting a hardline stance on Iran, are not eager to vote for a new war. Yet Trump also recognises that the combination of the nuclear threat and a humanitarian catastrophe creates a unique window of opportunity for actions that could gain support both domestically and internationally. A president known for his unpredictable decision-making style may decide to strike if he senses the moment is favourable and the political risks are minimal.

This dual threat—both from the nuclear programme and the repression—places the Iranian system in an extremely difficult position. Tehran understands that harshly suppressing the protests could provoke external intervention, but refraining from repression means losing internal control. A classic trap: any action worsens the situation. The Iranian leadership is trying to find a balance by applying repression in measured doses, but the January protests show that maintaining this balance is becoming increasingly difficult.

American intelligence is actively working with the Iranian opposition, providing technical means to bypass internet blockages and coordinating information campaigns. Now, military planning is being added to these efforts. The Pentagon is developing scenarios for limited strikes that can be framed as punishment for specific regime crimes rather than the start of a full-scale war. These could include Tomahawk cruise missile strikes from destroyers in the Persian Gulf on IRGC headquarters in Tehran and other cities, MQ-9 Reaper drone strikes on Basij bases and prisons like Evin, where political prisoners are held and tortured, and airstrikes by F-35 fighters and B-52 bombers on military facilities and weapons depots.

The logic is as follows: if the regime kills, say, a thousand people in a week or several hundred in a single day, Washington could respond with a strike, presenting it as retaliation for mass killings. After the strike, the U.S. would announce that the operation is over, but it could be repeated if the repression continues. This strategy allows the United States to avoid a protracted conflict while maintaining constant pressure on the clerical authorities. Trump has repeatedly stated that he does not want “new endless wars” but is prepared to use force “quickly, decisively, and effectively.”

The risks of this approach are enormous and multilayered. Iran will almost inevitably respond, and its response will be multi-directional. Hezbollah in Lebanon, despite suffering significant losses from Israeli strikes in recent years, still possesses missiles and projectiles of varying ranges and is capable of expanding attacks on Israeli cities, potentially reaching Haifa and central regions of the country. Tehran-aligned Shiite formations in Iraq, organised under the Hashd al-Shaabi structures, could escalate attacks on U.S. facilities and bases. The IRGC, in turn, might attempt to raise the stakes of the conflict by threatening shipping in the Strait of Hormuz, through which around 20–21 million barrels of oil per day pass—roughly one-fifth of global consumption. Even a partial disruption of traffic there could push prices into triple digits, trigger an inflationary shock in the global economy, slow growth in developed countries, and increase recessionary risks in emerging markets.

Inside Iran, the reaction to external strikes is unpredictable and could unfold along two opposite scenarios. On one hand, external aggression traditionally consolidates society around the authorities, even if those authorities are unpopular. Iranians, despite their dissatisfaction with the government, remain patriots. They could perceive U.S. strikes as an insult to their country. Protesters would face a moral dilemma: continue opposing their government under the bombs of an external “enemy” or temporarily unite with the authorities against the “aggressor.” The history of the Iran-Iraq War (1980–1988), when an external threat rallied the country around the newly established Islamic regime, serves as a reminder of how this mechanism works.

On the other hand, if the strikes are targeted specifically at the security forces suppressing protests, this could embolden the opposition to take decisive action. Protesters might interpret U.S. strikes not as aggression against Iran, but as assistance to the Iranian people against the regime. In that case, protests could intensify, placing the authorities under dual pressure: external military and internal political. This is precisely the scenario Trump is betting on, but there are no guarantees it will materialise. Too much depends on details: where the strikes are carried out, how many civilian casualties occur, how the regime portrays events in its propaganda, and how organised the opposition is at the critical moment.

In this scenario, Israel would have the opportunity to inflict maximum damage on Iran’s military apparatus with U.S. support, but it would also assume the risk of massive retaliatory strikes.

European capitals have expressed serious concern over the escalation in Iran, as well as the rising violence against peaceful protesters, calling for restraint, adherence to international law, and a diplomatic resolution. The EU has officially condemned the use of force against demonstrators and urged Iranian authorities to refrain from violence. Leaders of several countries, including France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, have issued statements supporting human rights and the need for dialogue, emphasising the risk of regional conflict escalation and the importance of de-escalating the crisis.

Russia finds itself in an extremely difficult position, further complicated by its entanglement in the war in Ukraine. Iran became an important partner for Moscow following the start of the so-called “special military operation” in February 2022. Iranian Shahed-136 drones, which Russian forces call “Geran-2,” and Fateh-series ballistic missiles are now used by Russian troops on a daily basis. Military cooperation has deepened to the level of joint weapons production: factories in Russia have been opened for licensed assembly of Iranian drones. Trade circumventing sanctions has tied the two economies closer than ever: annual trade has reached $5 billion, and Iran has become an important transit hub for Russian exports to Asia and Africa.

The Kremlin cannot afford to lose Iran, but it also lacks the resources to save it if a U.S.-Israeli operation begins. As noted earlier, Russia is bogged down in Ukraine, its military capacity is depleted, the economy is operating at the limits of its capabilities, and international isolation is deepening. Moscow publicly warns Washington against military intervention, expresses readiness to support Tehran, but makes no concrete commitments. On January 12, Russian Security Council Secretary Sergei Shoigu, in a phone call with Ali Larijani (Secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council), strongly condemned any attempts by external powers to interfere in Iran’s internal affairs.

Russia may provide Iran with intelligence on planned strikes via GLONASS satellite systems and electronic reconnaissance. But direct involvement in the conflict on Iran’s side is ruled out: Russia has neither the forces nor the will to fight the United States over Tehran. Moreover, within the Russian elite, there is an understanding that a prolonged U.S.–Iran conflict could benefit Moscow by diverting American attention and resources from Ukraine and creating manoeuvring opportunities. Therefore, Russian support for Iran is likely to be limited and symbolic—enough to maintain strategic relations, but insufficient to alter the course of events.

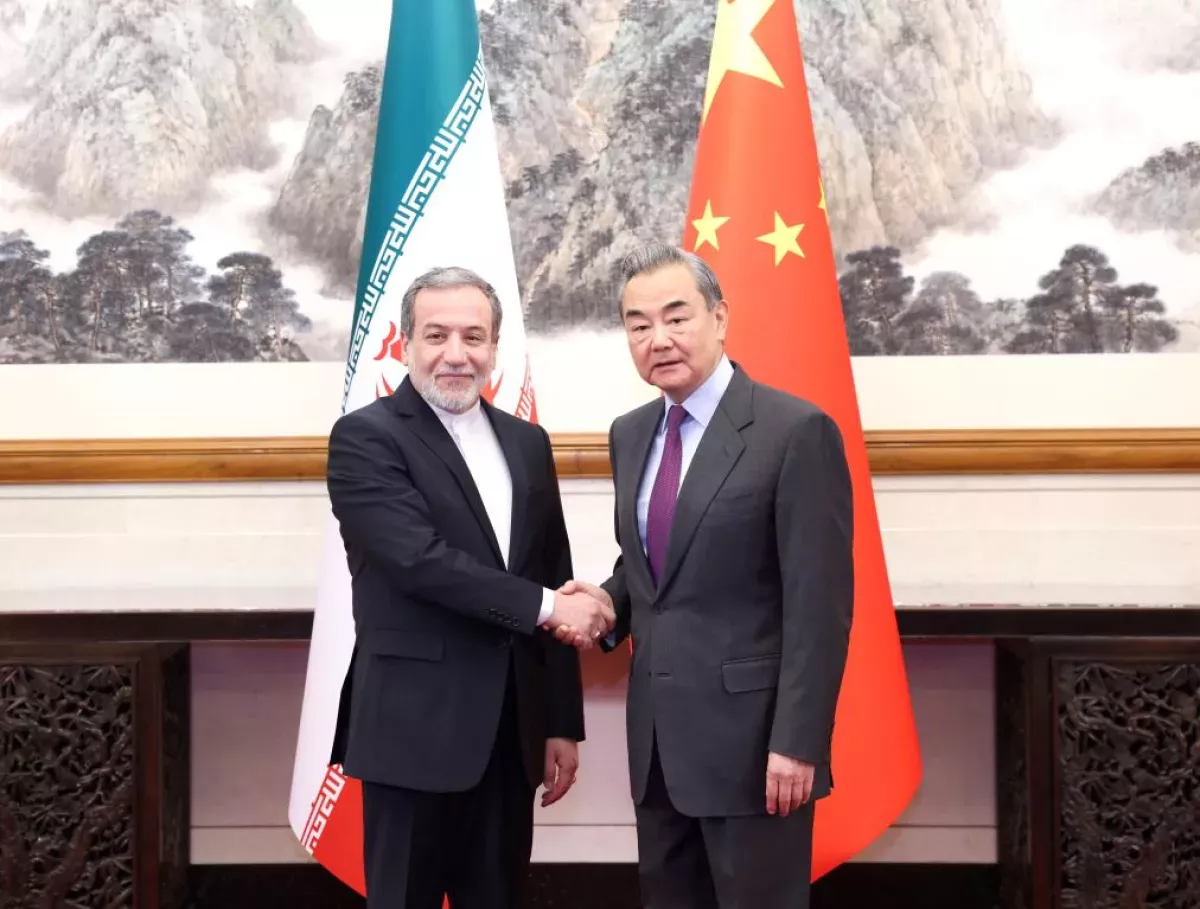

China approaches the Iranian crisis with the same cold pragmatism that defines its Middle East policy. Beijing needs regional stability to secure energy supplies and advance the Belt and Road Initiative, and Iran occupies an important place in this framework. China remains the largest buyer of Iranian oil, receiving around one million barrels per day through mechanisms that circumvent U.S. sanctions and provide Tehran with vital revenues. Iran is also important to Beijing as a transit hub between Central Asia and the Middle East, and as part of a broader strategy to build an alternative economic and geopolitical architecture outside U.S. control.

This relationship is anchored in the 25-year comprehensive cooperation agreement signed in 2021, envisaging large-scale partnerships in energy, infrastructure, and technology, although implementation has proceeded far more slowly than initially expected. At the same time, Beijing does not intend to turn Iran into a cause for direct confrontation with the United States. China’s official line remains diplomatically neutral—calling for dialogue, de-escalation, and restraint—allowing it to maintain strategic cooperation with Tehran without becoming entangled in a risky conflict with Washington.

Chinese diplomacy makes it clear to Tehran that it should not expect military support. If the U.S. and Israel carry out strikes, China will publicly condemn them at the UN and other international organisations, but it will take no practical steps to protect Iran. Beijing will prefer to ride out the crisis, continuing to purchase Iranian oil at even lower prices if sanctions tighten, and later build relations with whichever regime comes to power. China knows how to adapt and win in the long term without getting involved in short-term conflicts. This is a cold calculation, free of ideological illusions or emotional commitments.

The Gulf states are watching developments with growing concern. Saudi Arabia normalised relations with Tehran in March 2023 under Chinese mediation, and this normalisation brought certain benefits: regional tensions eased, proxy conflicts in Yemen and Iraq became less intense, and channels opened for dialogue on contentious issues. King Salman and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman viewed this as a strategic success, allowing them to focus on economic diversification under the “Saudi Vision 2030” programme.

But Riyadh does not have any sympathy for the Iranian regime and would not mind seeing it weakened. The Saudis remember decades of proxy wars, attacks on their oil facilities, and Iran’s support for Shiite insurgents in Saudi Arabia’s eastern provinces. The fall of the ayatollahs’ regime would remove a strategic threat and strengthen Saudi positions in the region. The problem is that the Saudis are deeply afraid of chaos. The experience of the “Arab Spring” is still too fresh: they saw how protests destroyed Libya, Syria, and Yemen, turning them into zones of permanent violence.

The UAE and Qatar are pursuing an even more cautious policy. Abu Dhabi and Doha maintain dialogue channels with all parties, offer themselves as mediators, and invest in relationships that will be useful regardless of the crisis’s outcome. These countries have learned to survive in conditions of permanent instability, balancing between conflicting powers and leveraging their geographic position and financial resources. The UAE, which normalised relations with Israel under the Abraham Accords in 2020, is in a particularly delicate position: it needs both good relations with Israel and to avoid conflict with Iran. Qatar, which maintains unique relations simultaneously with Iran, the U.S., and the Hamas movement, seeks to use its role as mediator to prevent escalation.

From this web of interests and contradictions, several possible scenarios could unfold in the coming weeks and months of 2026. These scenarios are not mutually exclusive and may overlap or shift from one to another depending on the actions of key actors and the random factors that always play a role in crisis situations.

The first scenario sees the Iranian system surviving through measured repression, avoiding mass killings out of fear of U.S. strikes. The IRGC would suppress protests harshly but selectively: detaining identifiable activists, dispersing demonstrations with water cannons and tear gas, using rubber bullets and batons, but trying to prevent casualty numbers from reaching hundreds in a single day. This represents an attempt to walk a fine line: maintain control while avoiding giving Washington a pretext for intervention.

The system would employ all available tools: surveillance via social media and messaging apps, mass arrests followed by intimidation, show trials, and propaganda campaigns portraying protesters as agents of foreign intelligence. In February and March, the regime may attempt to turn the tide by exhausting the protest movement, arresting a critical mass of activists, and sowing fear among the population.

The problem with this scenario is that it demands the impossible of the security forces: to suppress protests that continue for months, but to do so “carefully.” History shows that repression has its own logic of escalation. If the protests do not stop, if thousands of people take to the streets every day, and if the economic situation continues to deteriorate, the security forces become increasingly brutal. At some point—perhaps in late February or March—the regime may cross a line after which U.S. strikes could become inevitable.

The second scenario is an attempt at controlled liberalisation under the pressure of an external threat. Recognising the trap it is in, the government might make limited concessions in an effort to reduce the intensity of protests and deny Washington a moral justification for strikes. President Masoud Pezeshkian, who holds minimal real power but can serve as a façade for reforms, could, with the agreement of the Rahbar, announce the start of a dialogue with society. The regime might release several hundred political prisoners, including prominent figures, and declare a moratorium on executions for participation in protests.

Khamenei could deliver a speech acknowledging the “concerns of part of society” and calling for “national unity and dialogue,” without abandoning the fundamentals of the Islamic regime, but signalling a willingness for limited change. This could relieve pressure and buy time, splitting the protest movement between radicals demanding a complete regime change and moderates willing to accept reforms.

But such a strategy requires the Iranian authorities to be genuinely willing to implement real changes, not just create the appearance of reform. If concessions are perceived as a tactical manoeuvre, protests will only intensify. The history of controlled liberalisation in authoritarian regimes is full of failures: the USSR during perestroika, Egypt on the eve of the Arab Spring, and Tunisia under Ben Ali.

Moreover, the IRGC and the conservative clergy are categorically opposed to any reforms, seeing them as a betrayal of the revolution and the beginning of the end. If Pezeshkian attempts to implement reforms, he will face severe sabotage from the security forces. The IRGC could simply ignore presidential decrees while continuing repression. The guards might stage provocations, portraying reformers as traitors. In the most extreme case, the IRGC could remove Pezeshkian from office, accusing him of undermining national security.

Khamenei, for his part, is too old and too weak to impose a compromise line on the elites against their will. His authority rests on tradition and fear, but if the elites sense that he is losing control, they will begin to act independently, pursuing their own interests. Therefore, a scenario of managed liberalisation is possible only in the event of a radical shift in the balance of power within the regime, when one elite faction decides to sacrifice another in order to preserve the system. The likelihood of such a development in February–March 2026 is low, but not zero.

The third scenario is a gradual collapse of the system under the combined pressure of internal protests and external threats. The protests could drag on despite repression. The economy would continue to deteriorate, inflation would accelerate, subsidies would be cut, and bazaars would close. The regime would find itself unable either to crush the unrest by force—because of the threat of U.S. strikes—or to make concessions due to resistance within the elite. Power would begin to erode, and government orders would be implemented ever more slowly and ineffectively.

In February, the regions may begin to ignore directives from Tehran. Provincial governors could start making their own decisions on how to respond to protests, based on local realities. In March, the first signs of a split within the IRGC may emerge: junior officers will begin to hesitate, discussing among themselves the futility of defending corrupt generals. In April, one of the regional IRGC commanders might declare his defection to the side of the people, take control of his province, and call on others to follow his example.

At some point—likely by the summer of 2026—the system could collapse not as a result of an external strike, but due to its own inability to function. Khamenei would become so weakened that he would lose the capacity to perform his duties. The struggle over succession would escalate into open conflict among elite factions. One group would attempt to appoint a new Supreme Leader, while another would refuse to recognise his legitimacy. The IRGC would split, with different units backing different contenders.

This scenario could unfold over several months or up to a year, but its endpoint would be systemic change. The question is what might replace it, and how manageable the transition would be. If forces capable of taking power and maintaining order emerge—possibly a coalition of moderate IRGC officers, technocrats from Pezeshkian’s administration, and representatives of the secular opposition—Iran could avoid full-scale chaos. Such a coalition could declare a transitional period, announce elections, and dismantle the repressive apparatus while preserving state institutions.

But at present, there is no organised opposition. The protests are spontaneous and decentralised, with no recognised leaders and no clear programme. The Iranian diaspora in exile is fragmented: monarchists and supporters of Reza Pahlavi, the son of the last shah, have no real base inside the country; leftist groups, including remnants of the People’s Mojahedin and other organisations, are discredited by their cooperation with Saddam Hussein in the 1980s; and liberal democrats lack the organisational capacity to seize power.

Under these conditions, a regime collapse could lead to a period of anarchy, in which various groups compete for power through violence. Regional warlords, remnants of the IRGC, and criminal networks could all attempt to fill the power vacuum. Iran risks repeating the fate of Libya after the fall of Gaddafi or Syria after the outbreak of civil war: a prolonged conflict involving multiple actors, with no clear victor, massive human casualties, and the destruction of statehood.

The fourth scenario involves U.S.–Israeli strikes on Iran, either in response to mass killings of protesters or as a preventive operation against the nuclear programme, combined with a humanitarian justification. This option is becoming increasingly likely as the number of protesters killed rises, the rhetoric of Donald Trump and Benjamin Netanyahu intensifies, and the regime demonstrates its inability to manage the crisis.

The strikes could be launched in late February or March 2026 if the regime crosses a red line—killing several hundred people in a short period or employing particularly brutal methods to suppress protests. As noted above, the operation could begin with massive cruise missile strikes using Tomahawk missiles launched from destroyers and cruisers deployed in the Persian Gulf and the Arabian Sea. Targets could include IRGC command centres in Tehran, Isfahan, Mashhad, and other cities; the headquarters of the IRGC’s Quds Force; Basij training bases; military-industrial facilities; and weapons and ammunition depots. At the same time, Israel could carry out airstrikes on nuclear facilities in Natanz, Fordow, Isfahan, and Arak, using F-35I Adir and F-15I Ra'am fighters armed with GBU-31 and GBU-28 guided bombs.

The United States could also carry out MQ-9 Reaper drone strikes against prisons such as Evin, where political prisoners are held, presenting this as an operation to free innocent people. The strikes would be precise, aimed at minimising civilian casualties in order to preserve the moral justification of the operation, which would be framed as limited, target-specific, and not intended to occupy territory or overthrow the regime by force.

Trump would address the American public and the international community, explaining that the United States had been compelled to act in order to prevent the genocide of the Iranian people and to halt a nuclear programme threatening regional and global security. He would stress that the operation was over, but would be repeated if the regime continued killing its own citizens or attempted to restore nuclear facilities.

Inside Iran, the reaction to external strikes would be complex and contradictory. The regime would immediately declare martial law, announce the mobilisation of all forces to repel aggression, and call on the population to unite in the face of the enemy. State television—if not disabled by cyberattacks—would broadcast footage of destruction and civilian casualties, even if limited in number, portraying Americans and Israelis as killers and aggressors.

The fifth scenario is the fragmentation of Iran along ethnic lines. Its likelihood would increase if the regime weakens to a critical point as a result of internal collapse, external strikes, or a combination of both. Iran is a multi-ethnic state: Persians make up roughly half of the population, Azerbaijanis around one fifth, Kurds about ten per cent, Baluchis approximately five per cent, Arabs two to three per cent, while the remainder consists of Turkmens, Lurs, and other groups. These communities display varying degrees of loyalty to the central government and have very different historical experiences in their relations with Tehran.

If the centre loses its ability to control the territory—whether due to systemic internal breakdown or the destruction of the security apparatus as a result of potential US–Israeli strikes—the ethnic periphery may attempt to break away from central authority.

Iranian Azerbaijan in the north-west, home to tens of millions of Azerbaijanis, could demand broad autonomy or even independence. The Kurdish-populated regions in the west of the country, with six to eight million Kurds, already possess experience of self-organisation and maintain close links with Iraqi Kurds, who enjoy autonomous status, as well as with Kurdish structures in Syria. Baluchistan in the south-east—poor, marginalised, and locked in long-standing conflict with the Persian centre—risks turning into a zone of chaos. Baluchi tribes, with traditions of armed resistance and cross-border ties to Pakistan and Afghanistan, could, in the event of state collapse, seize control of their territory and establish a de facto independent entity.

The Arab population of oil-rich Khuzestan in the south-west of the country also harbours long-standing and deep grievances against Tehran. Local Arabs view themselves as a discriminated community, deprived of a fair share of the wealth extracted from their land. If central authority weakens, Khuzestan could become a focal point of struggle for control over oil fields, while tribal elites—potentially backed by individual Gulf states—may attempt to entrench autonomy or push even further.

Each of these scenarios produces its own winners and losers, yet the trajectory of events will be determined in the coming weeks and months. January 2026 may prove to be a turning point, after which one of these scenarios begins to unfold irreversibly. Iran’s fate will be decided in the struggle between protesters and the regime, between external pressure and internal resilience, and between the forces of disintegration and those of systemic preservation.

It is impossible to say with certainty which of these scenarios will materialise, but one conclusion is clear: the status quo is no longer viable. Iran is changing, and the key question is not whether transformation will occur, but how destructive it will be—and who will be capable of managing its consequences. The coming months will determine the trajectory, revealing whether the country is moving towards a managed transition, chaos, external intervention, or outright fragmentation.

The world is watching as this crisis unfolds, aware that its outcome has the potential to redraw the regional map and alter the global balance of power. Iran, with its population of 90 million, vast energy resources, and position at the crossroads of continents, is far too significant for its fate to remain a purely internal matter. Whatever happens in Tehran will reverberate in Washington, Moscow, Beijing, Riyadh, Tel Aviv, and many other capitals—and January 2026 may enter history as the moment when the old order in the Middle East began to crumble, while the contours of the new one remained obscured by the smoke of protests, the calculations of global power centres, and the uncertainty of the outcome.

By Adrian Volker, United Kingdom, exclusively for Caliber.Az