Lebanese statehood: between Hezbollah, the US whip, and Israeli bombs

U.S. and Israeli demands directed at the Lebanese government to disarm the pro-Iranian militia are accompanied by unprecedented pressure. Yet Hezbollah has no intention of making concessions.

The party leader, Naim Qassem, responded to the government’s demands to disarm with a categorical refusal. According to him, Hezbollah is willing to discuss with the government only plans for the joint defence of the country—and only after the withdrawal of Israeli forces. Hezbollah is joined by the leader of another Shiite party, Amal, Nabih Berri. Together, these forces control one-third of the seats in the Lebanese parliament.

Israel refuses to withdraw its troops from several areas in southern Lebanon, citing strategic high grounds that allow it to control shelling on Israeli territory.

Through special envoy Thomas Barrack, the U.S. proposed a plan to the Lebanese government that is extremely difficult to reject: either deeper sanctions, or lifting restrictions and receiving multi-billion-dollar investments from America’s allies—the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

Applying a carrot-and-stick approach, in early July the U.S. Department of the Treasury added seven Lebanese citizens to its sanctions list, accusing them of financing Hezbollah. The intentions of the American-Israeli coalition are obvious: “either you disarm Hezbollah, or your problems will only grow.”

At first glance, it seems strange that the pressure has no effect. One might think that the Lebanese government itself would be interested in disarming Hezbollah. But, as famously said in a cult film, “In my store, I’m the only one who kills!” This phrase perfectly reflects one of the core functions of a state—the monopoly on violence.

However, in Lebanon it is Hezbollah, not the state, that controls a number of territories. The group possesses its own network of schools, hospitals, supermarkets with subsidised goods, and its own army. Southern Lebanon, the Beqaa Valley, and the Shiite suburb of Beirut, Dahieh, are effectively under its control. The government’s influence in these areas is close to zero, calling into question the very existence of Lebanese statehood.

The country is going through a severe crisis. Most of the population lives below the poverty line, and youth unemployment reaches 50%. Fuel and energy shortages continue, alongside a “garbage crisis”—the authorities lack the funds to remove waste, and electricity is cut according to a schedule.

For decades, Lebanon’s economy was based on large banks, which received funds from the Lebanese diaspora and Syrian elites. But these banks collapsed, largely due to anti-Syrian sanctions and the civil war in Syria. Since 2019, Lebanon has been in a state of deep economic depression, triggering mass protests involving around two million people. These protests could flare up again.

It is unsurprising that the government is eager to attract Saudi and Emirati investments, especially since those in power are Christian and Sunni groups traditionally hostile to Hezbollah, particularly the Lebanese Forces party.

In August, the Cabinet of Ministers approved a plan proposed by Thomas Barrack: the gradual dismantling of all armed groups except for government forces. But Hezbollah refused once again.

The weakness of Hezbollah

For a long time, Hezbollah was the most powerful military actor in Lebanon, dictating the country’s politics despite holding only 12–15 parliamentary seats. Its 20,000–30,000-strong army, with commandos, infantry, and armoured units, effectively made it a “deep state.” Under its patronage were Amal and the Christian Free Patriotic Movement (FPM), while its allies included influential politicians and security officials, including former Prime Minister and billionaire Najib Mikati.

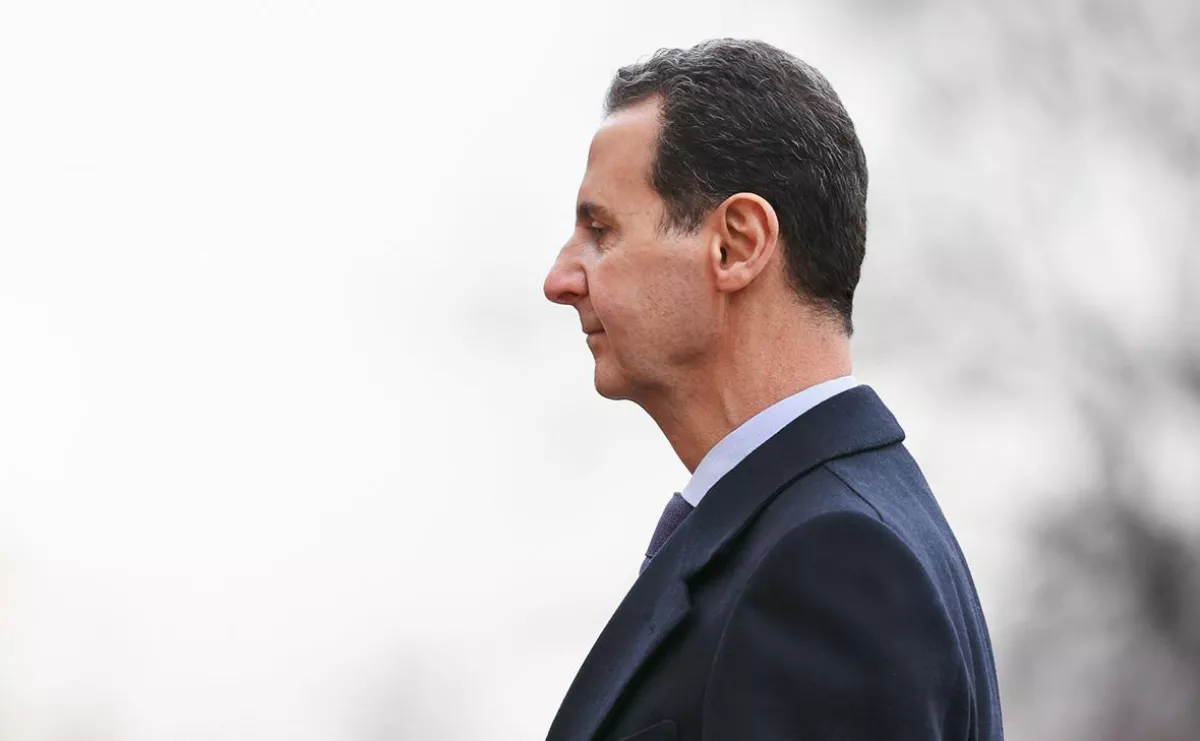

However, the organisation was severely weakened after heavy losses in the 2024 war with Israel. Its military and political leadership was wiped out in a “pager attack.” The fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria cut off the main channel for Iranian arms supplies. It is now unclear how Hezbollah could sustain prolonged fighting without stable logistics.

The assassination of Sheikh Hassan Nasrallah and experienced commanders such as Fouad Shukr deprived the group of the leaders who shaped its identity. Many Shiite homes have been destroyed by Israeli strikes, and the population is frustrated by the absence of promised aid. Financial flows from Iran have decreased, as the Islamic Republic itself faces a severe economic and military crisis.

Experts agree that the Lebanese government is not ready to fight Hezbollah. And since the group has no intention of disarming, the plans of the U.S., Israel, and Beirut itself remain merely declarative. Officials openly state that they do not want war with it.

The strength of Hezbollah

Nevertheless, the memory of the 1975–1990 civil war remains vivid, and society fears its repetition. No one except Hezbollah is prepared for a new war. Its fighters see killings and dying for the party as a “righteous cause.”

The leadership of Hezbollah, meanwhile, has long transformed into a corporation profiting from drug trafficking, the trade in precious stones, and control of currency exchanges. It is a financial empire and simultaneously a drug cartel, owned by the wealthiest Shiite clans connected to Iran.

Most Shiites do not directly benefit from its activities, but fighters receive stable salaries and training from a young age. Opponents lack such resources. Therefore, where some are willing to fight and others are not, the outcome is predetermined.

Even today, Hezbollah may rival the Lebanese army in military strength. Its core is composed of veterans of the Syrian war. Meanwhile, the army suffers from clan-based divisions: up to half of its personnel and a third of its officers are Shiites, many of whom are related to Hezbollah. The current Chief of Staff also cooperates with the group.

Moreover, the civil wars in Syria and Lebanon have shown that unarmed communities become victims of purges, looting, and kidnappings. As a result, some Shiites view Hezbollah as a protector—a perception actively reinforced by its propaganda.

A potential unification of different communities on a social basis could have posed a challenge to Hezbollah, as happened in 2019, when protests brought together the poorest Christians, Sunnis, and Shiites, as well as residents of Syrian and Palestinian refugee camps. But at that time, the movement was disorganised and weak. Today, nothing of the sort exists in Lebanon.

Conclusion

Even weakened and having lost many positions, Hezbollah remains too strong for the government to risk a direct confrontation. To its question—“We will not disarm, and what will you do to us?”—Beirut has no answer.

Most likely, President Joseph Aoun and Prime Minister Nawaf Salam will simulate willingness to comply with U.S. and Israeli demands, while in practice buying time to avoid new sanctions and strikes.

The Lebanese government is trying to walk a tightrope—navigating between external pressure and internal threats. How successfully it manages this balancing act remains to be seen.