Turbulent times in Afghanistan Internet blackout fuels coup rumours

Recently, the Taliban cut off phone and internet services in Afghanistan amid rumours of a coup attempt and threats of a potential U.S. intervention. However, Afghan authorities later denied reports of a nationwide internet shutdown. According to officials, the disruptions were linked to the wear and replacement of old fibre-optic cables.

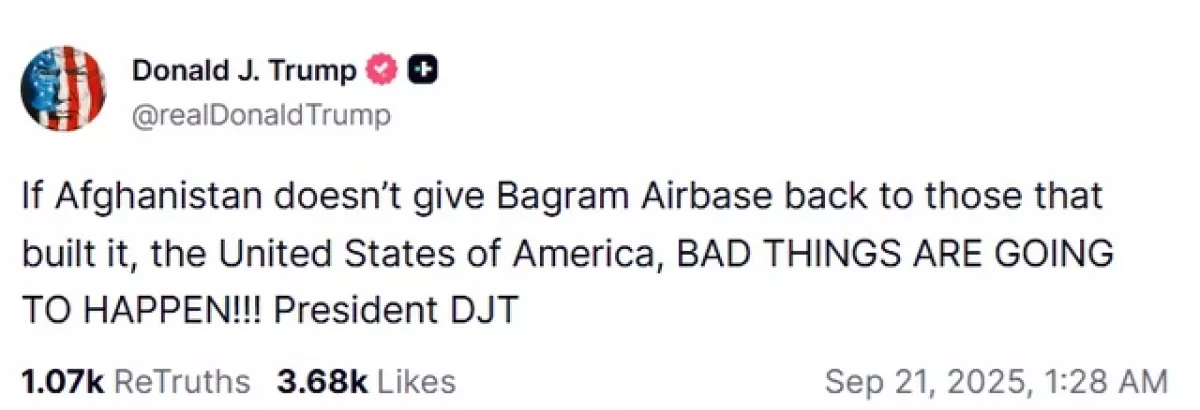

Recently, Donald Trump made strong statements regarding the former U.S. military base at Bagram in Afghanistan. He stressed the base’s importance to the United States and noted that its proximity to China makes it critically significant for American interests.

The U.S. president added: “I was getting out, but I was going to keep Bagram. Right now, China has Bagram. I was going to keep one of the biggest airbases in the world, they left it.” Trump hinted at Taliban connections with China, although there is no evidence to suggest that Beijing has taken control of Bagram.

Trump has repeatedly emphasised the importance of Bagram for the United States. Earlier, during his election campaign, he criticised the withdrawal of American troops from Afghanistan in 2021, carried out by former President Joe Biden’s administration, and promised that if re-elected, he would return Bagram under U.S. control.

On September 19, The Wall Street Journal reported that the United States intends to resume its military presence in Afghanistan. Allegedly, administration officials are holding talks with the government of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, with the Taliban, about restoring the U.S. military presence at Bagram Air Base.

U.S. policy toward Afghanistan and its future relations with the Taliban’s interim government remain uncertain. Political analyst Mohammad Amin Karim reacted to Trump’s statements by saying: “Reclaiming Bagram Airbase is nothing more than a dream, an illusion, and madness. It will never happen again.”

Bagram is an ancient city and a major airfield located 60 kilometres north of Kabul. It is hard to imagine that the Americans would attempt to reignite a war with the Taliban just to hold onto a single base, surrounded on all sides by adversaries. It is also doubtful that the Taliban would agree to let Americans back in voluntarily. The United States fought this movement for 20 years during its occupation of Afghanistan and was ultimately forced to leave the country, after which the Taliban took power.

Nevertheless, rumours have begun circulating that the United States may attempt to reclaim Bagram.

In the meantime, the Taliban have shut down internet and mobile communications in Afghanistan. This came after the government pledged to restrict access to the network as part of its fight against “immoral activity.” The move resulted in a “complete internet blackout” in a country of 43 million people.

For the first time since the Taliban came to power, a nationwide communications blackout has occurred. Internet and mobile services were cut off “until further notice,” according to reports from Afghanistan. The shutdown affected not only ordinary citizens but also the banking sector, customs services, and the wider economy.

It would be a mistake to think that Afghanistan is populated exclusively by shepherds and medieval artisans engaged in subsistence farming. Without mobile communication and internet, the country’s economy is severely undermined. According to available data, about 18% of the population uses the internet and 56% rely on mobile services. The disruption has hit not only banks but also street vendors and small and micro businesses, which form the backbone of the economy. People are outraged — internet and mobile connectivity are vital for conducting business. Entrepreneurs rely heavily on modern communication tools to negotiate deals. Without them, the economy of the capital and several other regions will be partially paralysed.

The Afghan capital, Kabul, is a city of more than 4 million people. If the ruling Taliban movement intends to dismantle daily life in this metropolis, it will face a host of serious challenges.

The notion that the Taliban are somehow an inherent, native phenomenon in Afghanistan, and that their return to power following the end of the U.S. occupation in 2021 was positively received by the majority of the population, appears doubtful.

Although the U.S. government acted harshly during its occupation — bombing areas where Taliban guerrilla resistance was active — Afghanistan’s GDP nevertheless quadrupled under American rule and the puppet regime it created.

At the same time, the country’s population doubled, and Afghanistan remained one of the poorest states in the world. While the U.S. did not contribute to scientific, technological, or industrial modernisation, it did help build quality roads, open hundreds of schools, allow women relatively free access to education and employment, and ensure that ethnic minorities were, by and large, not subjected to violence. The Afghan state budget was largely funded by generous American and international donations, though a significant portion of it was siphoned off by local officials.

The Taliban seized power after the withdrawal of U.S. troops. The movement itself emerged in the 1990s out of the Islamist–Sunni Deobandi current, which originated in India in the 19th century. By the late 20th century, the Deobandi doctrine had gained influence among several dozen wealthy Pashtun khan families. Drawing on extensive family and tribal networks, they created their own military group and later a civil administration in some regions, actively recruiting support from Pashtun tribes.

However, neither the Deobandi nor even the Pashtuns make up the majority of Afghanistan’s population. Pashtun tribes, according to varying estimates, account for between 40 and 50 per cent of the population. They are followed by Tajiks and Hazaras, who speak languages close to Farsi. In addition, other peoples such as Uzbeks and Kyrgyz also live in the country.

Tajiks and Hazaras make up the overwhelming majority of Kabul’s residents. The Hazaras, who constitute around 20 per cent of the capital’s population, are Shiite Muslims. In this large Persian-speaking city, women are far more open and educated, while men are significantly less conservative than the Taliban. The latter, however, adhere to peculiar customs uncharacteristic of most Afghans—for example, when seeing a woman, they avert their eyes to avoid “sinning.” As some Iranian clerics jokingly remark, “Our faith is not so weak as to be lost with just one glance at a woman.”

Indeed, the Taliban–Deobandi movement has a peculiar fixation on the “women’s question.” Drafting and enacting various laws restricting women’s rights has become their calling card—from banning work and education to forbidding women from appearing in public without being accompanied by male relatives. In practice, these measures have devastated the livelihoods of many families where women were breadwinners.

The Taliban have never won an election, nor could they, since they are essentially a military-political and ideological faction. They simply seized power by force and imposed their own order. Now, this group—alien to the majority of Afghans in terms of culture, religion, and tribal identity—has also decided to cripple the economy.

The truth is that most Afghans accepted Taliban rule. Not because they shared its ideology, but because they were weary of the wars that had torn the country apart for decades. The Taliban established order, improved tax collection—which they promised to spend on public needs—and thus earned, if not trust, then at least the temporary loyalty of the majority, including Kabul residents. Hardly anyone is willing to fight them to end their rule. As for peaceful protests, they have no effect: the Taliban beat and arrest demonstrators. As some Afghans told the author of these lines, the Taliban have come to govern the country for several decades, and almost everyone will accept this, since Afghans no longer want to fight.

But what if, instead of maintaining order, the Taliban end up destroying the economy? Then the situation will take a very different and far more serious turn. Faced with hunger, the majority is unlikely to tolerate the rule of a sect alien and distasteful to them.

That leaves the question: what was really behind the shutdown of the internet and mobile networks? Was it truly part of the sect’s fight against “immorality”? Or was it linked to preparations for repelling an American intervention? Or perhaps to something else altogether?

Unconfirmed reports have emerged claiming that Taliban leader Hibatullah Akhundzada has dismissed Sirajuddin Haqqani (Interior Minister) and Mohammad Yaqoob (Defence Minister).

Why does this matter? The Taliban effectively have two centres of power and two capitals: Kabul, where the main government institutions are located, and Kandahar, where the emir resides. Meanwhile, the so-called Haqqani Network, led by Sirajuddin and tied to al-Qaeda militants, functions as an independent military organisation that hardly answers to the emir. This group, only nominally part of the Taliban, has turned the Interior Ministry into a super-agency with the broadest powers.

If the emir has indeed dismissed Haqqani, it is doubtful he will comply. And if he does not, Afghanistan could be heading toward civil war. In that case, the shutdown of the internet and electricity may have been aimed at preventing Haqqani’s supporters from organising. Still, the claims about the dismissal of Haqqani and Yaqoob remain unverified and may ultimately prove false.

Meanwhile, new reports suggest that internet and mobile services have been restored in Kabul, though the situation in other Afghan cities remains unclear.