EU: The weakest link among middle powers Caught between giants

Among the Western middle powers, the European Union will face the greatest difficulty in the new world of geopolitical confrontation, where forces, resources, and intellect must be deployed on a full 360-degree scale. The institutional framework and ideological foundation of this union were created and refined for the realities of a completely different world.

A new topic is emerging in Western—and especially European—political and media circles. Or, as they like to put it, a new narrative. Its essence is that, due to the extreme uncertainty in international politics and the brazen use of power by the world’s major states, including the United States, other Western countries now need to unite their efforts to protect their own interests. Unlike what Washington’s allies have been accustomed to over the past decades, they now have to defend their interests on a full 360-degree scale—that is, not only against threats from Russia or China, traditionally seen as challenges, but also from the United States itself.

Liberals of all countries, unite!

Fresh impulses for this narrative come from statements by leaders of various Western countries and institutions, who are increasingly critical of the actions of Donald Trump’s administration. Perhaps the loudest and most eloquent of these was the speech by Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney at the World Economic Forum.

Carney’s speech in Davos seems like a genuine revelation. Many of the points he raised require careful reflection, as they touch on layers of what, until recently, was perceived as a rigidly uncompromising liberal notion of the “ideal.” Yet one of his central arguments boiled down to a fairly simple idea: so-called “middle powers” need to join forces to resist pressure from the most powerful states—the great powers. This argument was quickly picked up by some European leaders.

Nothing is surprising or unusual in Carney’s words. They reflect a natural reaction to the geopolitical changes occurring in the world. It has always been this way, and it always will be. If the power of the strongest states begins to threaten international stability and the interests of smaller countries, the latter seek ways to protect themselves—through mutual cooperation and more subtle diplomacy. This is a kind of alphabet, the most basic law of international relations.

What is strange is that such ideas had not been voiced earlier by Europe and other U.S. allies. For decades, the Western media-political mainstream—especially in Europe—actively pushed them aside as either archaic or politically incorrect. It was assumed that geopolitics, with its power balances and the necessity of daily delicate diplomatic manoeuvring, belonged to the past. Even the very use of the word “geopolitics” was practically taboo in many Western capitals.

As Brussels officials, for example, liked to repeat over and over, “The EU does not conduct—and will never conduct—geopolitics.” As a result, the very word was seen as a mark of bad taste and poor upbringing. Geopolitics was regarded as some kind of heresy, a vulgar relic of the past, incompatible with the enlightened liberal paradigm of 21st-century international relations.

Now, however, with the liberal paradigm disrupted, its adherents are facing the most serious challenges in the areas of security and development. Even they are beginning to realise that moral appeals and calls to return to a rules-based, bright world are not enough to fix the situation. That is why they are starting to look for effective alternatives. Increasingly and more loudly, they are urging each other to unite their efforts to protect their interests in an anarchic world. Consequently, dusty European archives are being reopened to public view, and geopolitical concepts—such as the “middle powers” framework—are being dusted off.

Let us emphasise once again: there is nothing surprising or, let alone, blameworthy in this. It is a natural reaction to what is happening—and it will only grow stronger with time. The truth is, however, that the newly emerged supporters of geopolitical concepts in Europe and some other Western capitals do not seem to fully understand their real practical significance in the world we live in today. Just as before, without proper understanding, they proclaimed the “end of geopolitics,” now—with a similar unconscious zeal—they are becoming its advocates.

Middle powers and geopolitics

The size of states is one of the fundamental concepts in the theory of international relations. It becomes geopolitical when linked to various factors of power and influence, which, one way or another, relate to geography and the spatial distribution of interests. And this is not only about territorial size or other purely quantitative indicators.

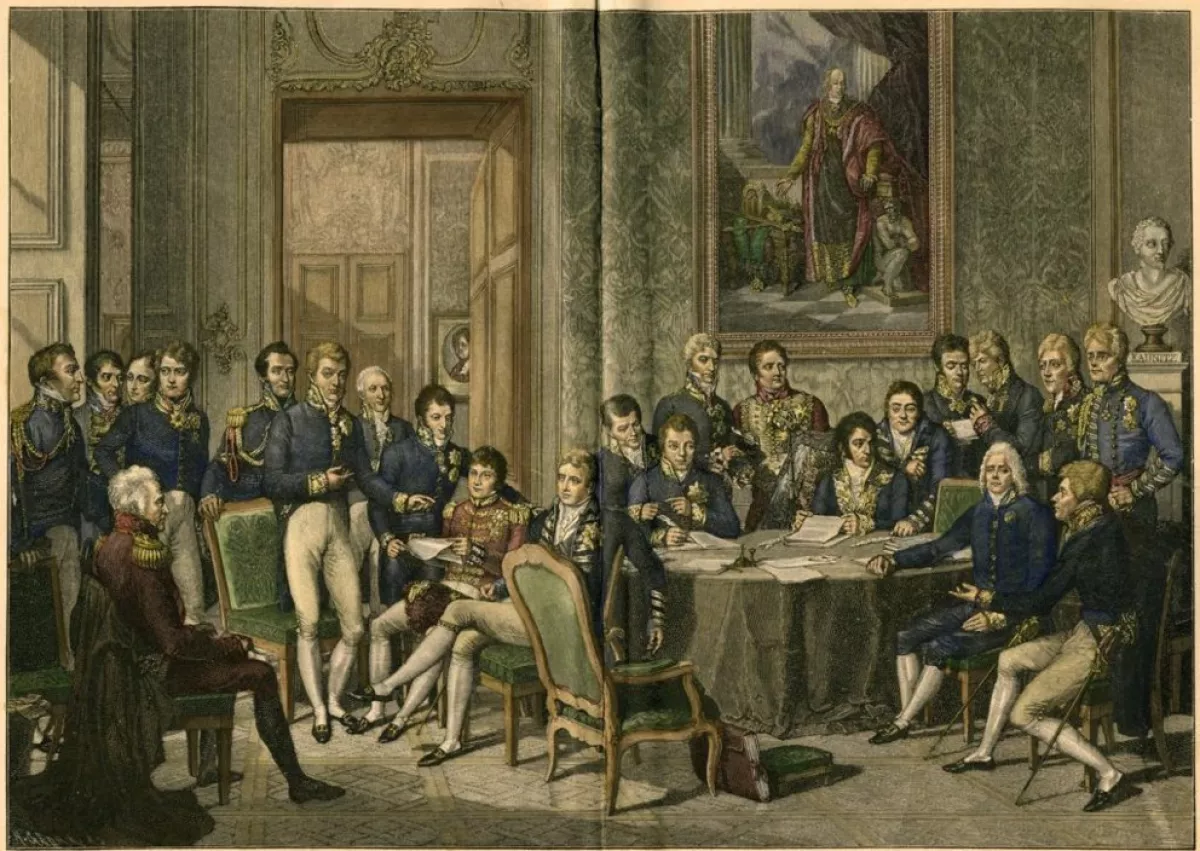

Scholars usually distinguish three types of states by their size in international relations: great powers, middle powers, and small countries. Historically, this classification dates back to the Congress of Vienna in 1815, where it was used to structure complex diplomatic negotiations. In many contexts, it is quite difficult to draw clear distinctions between middle powers and small countries. For example, when all of them confront directly the dominant power and political will of the most powerful actors in world politics—the great powers. In such circumstances, the differences between small and middle powers fade, and what comes to the fore are their shared weaknesses and vulnerabilities in the face of the overwhelming strength of the more powerful.

Here, in all its clarity, applies the law that Thucydides observed as early as 431 BCE: “The strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must.”

The main difference between middle powers (and small countries) and great powers is that they cannot independently create their own security environment. They lack the sovereign resources and favourable power arrangements to do so. As a result, they are forced, to some degree, to adapt to external conditions, often even accepting externally imposed rules of the game and defending their interests within those constraints.

Today, this characterisation significantly expands the list of middle powers. Among Western countries, it includes not only Canada, whose prime minister delivered a corresponding manifesto, but also, for example, Australia or Japan. In this same category, in a world of increasing power-driven anarchy, falls the European Union, even though many of its officials still like to describe the EU as a “trading and values superpower.”

In the current conditions, the natural way for middle powers to defend their interests and somehow resist the dominant force of great powers is to join forces with other middle powers and small countries that share similar vulnerabilities and face analogous challenges. By cooperating with these “partners in adversity,” the effectiveness and capabilities of such states increase substantially. This applies to security, as well as economic or infrastructure cooperation.

EU will face the greatest difficulty

In this sense, the Canadian prime minister’s call for middle powers to unite in the context of the collapse of the world order that had existed for decades is consistent with historical norms and, overall, rational. Likewise, the positive responses to this call from many European leaders are rational. This represents the embryonic stage of the very counterbalancing coalition against American claims to unilateral global dominance—a development we forecasted following the U.S. operation in Venezuela.

The problem is that turning this call into reality cannot happen through loud speeches from high political platforms or flashy media headlines alone. It is also not enough, for example, to sharply increase defence spending—neither the 5% of GDP promised to Trump at the NATO summit in The Hague, nor 10%, or even a hypothetical 15%, would suffice.

The main key to success for middle powers in defending their own interests in the face of the dominant power of great states is internal unity regarding their goals, and the ability to implement an optimal domestic and foreign policy based on that unity. Accordingly, their primary threat lies not so much in the policies of the great powers, but in their own inability to mobilise all available resources and pursue the most flexible, subtle—or even cunning—policies to protect their interests.

By these criteria, among Western middle powers, the European Union will face the greatest difficulty in the new world of geopolitical confrontation, where forces, resources, and intellect must now be deployed on a full 360-degree scale. The institutional foundation of this union was created and refined for the realities of a completely different world. For decades, European elites and societies have been indoctrinated with ideas and reference points from a different historical era. The results of this are clearly visible today in the actions of European politicians and officials at various levels. This is also reflected in the heated debates within the EU over what stance to take toward Washington: whether to openly confront it or try to appease the Trump administration with compliant rhetoric.

However, nothing under the sun is eternal. The European Union, too, will have to change under the pressure of the real world. Observing this process will be extremely interesting. It could lead either to the disintegration of the European integration project or to its relaunch under new conditions. Yet this process will be challenging for everyone involved—both the EU itself and its neighbours across Eurasia.