Georgian disillusionment with NATO “Carrot on a stick”

As is well known, one of Georgia’s goals in seeking NATO membership was the restoration of the country’s territorial integrity. However, actual events have shown that Azerbaijan was able to restore its territorial integrity without anyone’s assistance. Azerbaijan did not aspire to NATO membership, did not rely on support from the Alliance, and at the same time continued mutually beneficial cooperation with Russia.

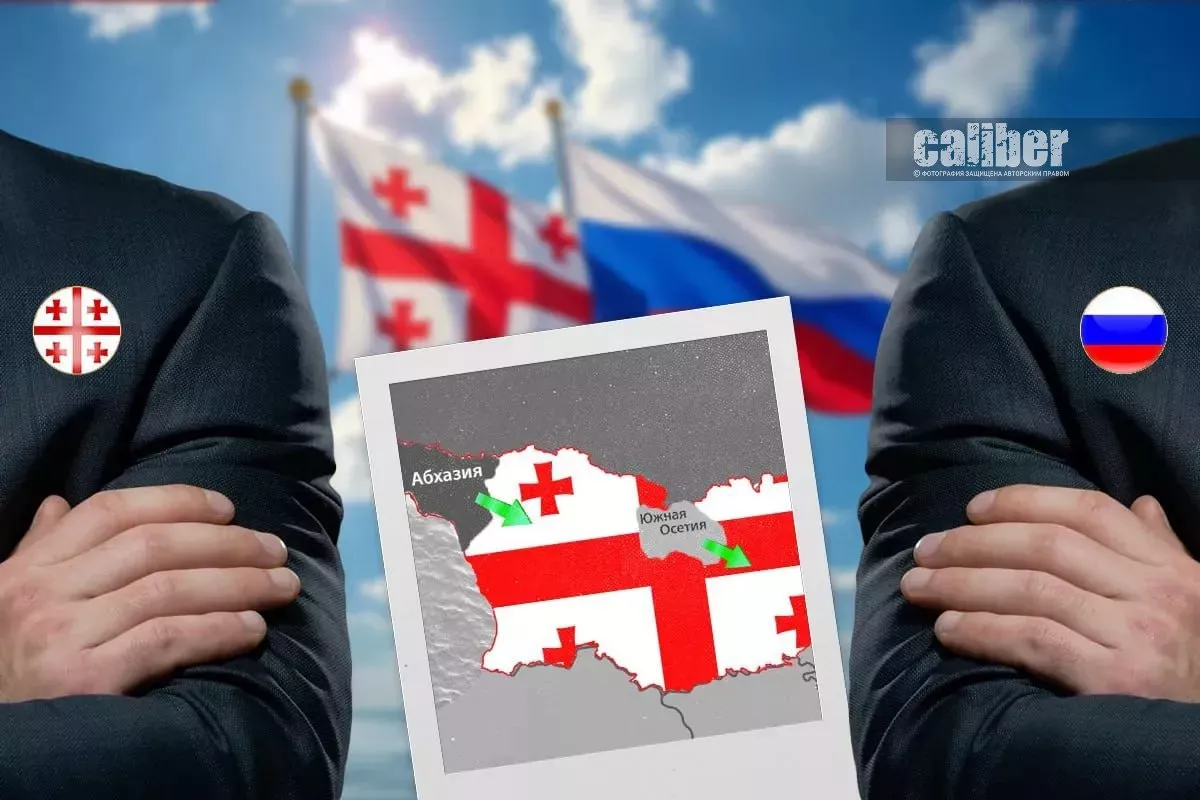

In contrast, Georgia’s pursuit of NATO membership brought the country nothing but a conflict with Russia that ended in disaster. Although the final declaration of the NATO Bucharest Summit on April 3, 2008, stated that Georgia and Ukraine would “eventually” become members of the Alliance, Georgia received no real assistance from NATO during the August 2008 war. The issue of territorial integrity, which before the 2008 conflict had officially not even been challenged by Russia, became a key obstacle to Georgia’s path to membership.

The fate of Ukraine has turned out to be even more tragic. Like Georgia, it declared its aspiration to join NATO. It has lost—and continues to lose—territory while waging a bloody war with Russia. One of the conditions for achieving the urgently needed ceasefire for war-ravaged Ukraine remains renouncing NATO membership—a membership that, like Georgia, Ukraine has never been able to approach in practice.

Despite this experience, Georgia’s pro-Western opposition and its external patrons continue to treat NATO membership as a key instrument for exerting pressure on the country and drawing it into an external agenda. It has reached the point where the embassy of neutral Switzerland officially “reminded” Georgia of the need to comply with Article 78 of the Constitution, which obliges the authorities to “take all measures within the scope of their competences to ensure the full integration of Georgia into the European Union and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.” This article was adopted at a time when Georgia still held hopes—essentially, illusions—about quickly achieving full NATO membership, which have never materialised.

This has created a situation in which Georgia’s constitutionally declared aspiration to join NATO has become effectively unattainable, yet at the same time serves as a convenient pretext for external interference in the country’s internal affairs. As a result, Georgian officials are increasingly questioning the necessity of continuing the course toward Alliance membership.

Thus, the Speaker of the Georgian Parliament, Shalva Papuashvili, compared the promise of future NATO membership to the well-known metaphor of a “carrot dangling in front of a donkey.” According to him, NATO itself has still not made any decisions regarding Georgia’s membership, and the declarations of “open doors” have, de facto, turned into that very “carrot” hung before the “domestic livestock” that will never be able to reach it.

“In reality, NATO has not made a determination regarding its enlargement, and the so-called open doors for Georgia are like a carrot hanging before livestock—a motivator to move in the desired direction, but the livestock will never reach that carrot. This is the bitter reality we see. We have nothing to complain about—Ukraine is shedding blood for this. The war started because of NATO membership—for the right to become a NATO member—that is why Ukraine is fighting,” Papuashvili said.

Shalva Papuashvili’s new statement proved even sharper than his previous reaction to NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte’s expressed “concern” over the situation in Georgia. At that time, the Speaker had already stressed that “the ball is on the Alliance’s side” and that Georgia had fulfilled everything necessary for membership.

According to him, 17 years have passed since the “open doors” declaration, during which Georgia has met the requirements both institutionally and militarily, participating in NATO operations and sending a contingent to Afghanistan that “was ten times larger than the Dutch one.” Despite this, a decision on membership has still not been made. Papuashvili emphasised that Georgian society is “no longer naive enough” to tolerate uncertainty and repeated reproaches from NATO.

He noted that keeping Georgia, Ukraine, and other countries in limbo only increases security risks. To illustrate, he reminded that Ukraine also received promises in 2008 but still has not received a membership decision: “When the war began, Zelenskyy requested a direct answer—whether NATO would accept Ukraine or not.”

Papuashvili stated that by many compatibility indicators, Georgia “outperforms 7–8 NATO countries,” yet the Alliance has still not determined what it wants. In his view, the Alliance must either accept Georgia or stop giving it political instructions based on long-standing promises.

“Year after year, we stand at open doors, exposed to drafts—instead of a decision being made. Regarding Ukraine, we hear statements that it will not become a NATO member. For three years, Ukraine has been fighting, including for its right to join the Alliance. Neither the Georgian nor the Ukrainian people will remain naive. NATO must decide what it wants. Keeping peoples in such confusion is unacceptable. The Georgian people are no longer naive enough to believe beautiful words: ‘The doors are open,’ ‘We are waiting’… No ‘open doors’ or ‘invitations’ are needed—what is needed are decisions,” Shalva Papuashvili stressed at the time.

However, two weeks later, Papuashvili no longer even spoke about the necessity of Georgia’s admission to NATO. In doing so, he effectively indicated that the Georgian authorities had realised the cost of such promises and their political purpose. Essentially, an information campaign targeting NATO had been launched “from above” in the country.

The Georgian population is also becoming increasingly disillusioned with the Alliance—this is confirmed both by sociological surveys and by the fact that citizens are unwilling to participate en masse in opposition rallies under pro-NATO slogans. Most importantly, abandoning the aspiration to NATO membership, including making corresponding amendments to the Constitution, could very well become the basis for a “reset” in relations between Tbilisi and Moscow.

Georgia, of course, will inevitably continue to demand from Russia the de-occupation of Abkhazia and the Tskhinvali region, as well as the withdrawal of recognition of their so-called “independence.” Under the current tense negotiations mediated by the United States regarding a settlement in Ukraine, such decisions from Moscow are highly unlikely. However, once the negotiations conclude and the peace process begins, a “window of opportunity” could open for Georgia.

For Russia, having concluded the war in Ukraine, it will be important to demonstrate, using Georgia as an example, that abandoning the NATO path can be “rewarded.” In turn, the Georgian leadership, by publicly questioning the feasibility of its Euro-Atlantic course, is in fact preparing for future negotiations with Moscow over the fate of the occupied territories. Until the war in Ukraine is fully resolved, concessions from Russia on these regions remain unlikely. Yet the post-war situation could well prompt Moscow to adjust its policy in the South Caucasus—not least considering Russia’s interest in regional transit corridors.

By Vladimir Tskhvediani, Georgia, exclusively for Caliber.Az