Israel and Hezbollah: A pause between wars A truce or a ticking clock?

In recent weeks, Israel has intensified its pressure on Hezbollah, the militant group controlling southern Lebanon. According to official statements, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) “eliminated a terrorist affiliated with Iran’s Imam Hossein Division in Lebanon, who was also a member of Hezbollah.” The Imam Hossein Division operates under Iran’s Quds Force — the elite unit responsible for covert operations abroad.

Reports also indicate that a commander of Hezbollah’s elite Radwan Brigade — a unit trained for deep infiltration missions behind enemy lines — was killed. It remains unclear whether this occurred during the same strike or in a separate incident.

These attacks on Lebanese territory are far from isolated. The Israeli Air Force continues to carry out regular airstrikes on Hezbollah positions, targeting the group’s commanders, weapons depots, and military infrastructure. Meanwhile, Hezbollah has so far refrained from launching retaliatory strikes against Israeli territory.

In November 2024, the two sides signed a ceasefire agreement brokered by the United States after a prolonged exchange of strikes. Today, they accuse each other of violating its terms. Israel has not withdrawn from five strategic areas it captured in southern Lebanon, despite being obliged to do so. On the other hand, the agreement stipulated the disarmament of Hezbollah, but the group had no intention of complying with that clause. Despite these violations, Hezbollah has so far continued to observe the ceasefire.

What is behind Israel’s new strikes?

“Hezbollah is constantly taking hits, but it’s also trying to rearm and recuperate,” said Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. “We won’t let Lebanon become a renewed front against us, and we’ll do what’s necessary.”

These statements have caused serious concern within Lebanon itself, whose population has no desire to return to the situation of 2023–2024. At that time, Hezbollah and Israel exchanged heavy strikes, during which the Israeli Air Force and artillery destroyed villages and urban districts. In northern Israel, a 10–15 km strip along the border was virtually depopulated: up to 100,000 Israelis and around one million Lebanese (mostly Shiites) became refugees. Today, these people are only just beginning to rebuild their lives.

Meanwhile, Netanyahu’s statements sound like an unambiguous threat. Despite Hezbollah’s current non-retaliatory tactics, Israel continues its attacks and may at any moment intensify them, once again applying the so-called “Dahiya Doctrine” — named after the Beirut suburb of Dahiya, repeatedly targeted by the Israeli Air Force. The Dahiya Doctrine calls for the total destruction not only of the enemy’s military targets but also of its civilian infrastructure. By devastating Shiite-populated areas in southern Lebanon, Israel effectively forced local residents — many of whom are loyal to Hezbollah — to flee these regions. Neighbouring Christian villages and districts suffered far less damage.

Why doesn’t Hezbollah respond to the strikes?

In short, the reason is this: Hezbollah was severely weakened after its unsuccessful war of 2023–2024, and is now regrouping and rebuilding its strength in preparation for a new round of conflict. Aware of this, Israel is carrying out systematic strikes aimed at preventing the group’s reorganisation.

According to Hanin Ghaddar, an expert on Lebanon’s political and social system, Hezbollah had several key pillars of support in the recent past.

First, it was seen as both the military protector and a source of social support for the Shiite community, which makes up roughly one-third of Lebanon’s six-million population. The group enjoyed the backing of a significant, though not dominant, portion of Shiites. It defended them from external threats and built an extensive social welfare network — from taxi services and affordable schools and hospitals to supermarkets and pharmacies where the organisation’s supporters could purchase subsidised goods. In addition, Hezbollah paid salaries to its fighters. All of this represented meaningful support for a population in which half of the people live below the poverty line.

Second, Hezbollah possessed the most powerful armed forces in the country — stronger even than the national army. As Mao Zedong once said, “Power grows out of the barrel of a gun.” He was criticised for it, but in Lebanon’s case, that principle has often proved true. Hezbollah responded to criticism with threats and violence, and its opponents often faced severe consequences. The group has been accused of political assassinations. Naturally, it has denied these allegations, but many Lebanese — including Shiites — are simply afraid to criticise it openly.

Third, Hezbollah relied on a network of domestic political alliances. A number of parties linked to various ethno-religious communities — such as the Shiite Amal movement and the major Christian Free Patriotic Movement (FPM) — preferred to cooperate with Hezbollah, sharing ministerial posts and government influence.

Finally, Hezbollah remained part of the so-called “Axis of Resistance” — an alliance of pro-Iranian parties and armed groups across the Middle East that receive funding and military support from Tehran. For Iran, Hezbollah is a crucial instrument of foreign policy, expansion, and resistance against the United States and Israel.

By 2024, all four of Hezbollah’s pillars of support began to crumble.

The group’s military power has been severely weakened by Israeli strikes, which killed much of its political and military leadership — including second-tier commanders — and destroyed numerous bases and weapons depots.

The devastation of Shiite villages and districts in southern Lebanon has turned about one million Lebanese into refugees, yet Hezbollah no longer has the means to provide assistance or rebuild housing. Although the group is wealthy and maintains international business connections, it simply lacks the necessary resources.

Meanwhile, Iran — which previously provided Hezbollah with between $600 million and $1 billion annually — has been weakened by its own internal crises and has reduced the scale of its financial support. This has undermined Hezbollah’s influence among the Shiite population. After all, it was Hezbollah that dragged Lebanon into the war with Israel in 2023, as a result of which vast numbers of people, primarily Shiites, lost their homes, and the organisation’s leadership has since shown little urgency in helping them.

The fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria in December last year deprived Hezbollah of its main logistical hub through which it had received Iranian weapons.

In addition, the group’s weakened position caused its allies to turn away from it — first and foremost, the Christian Free Patriotic Movement (FPM). This shift, backed by U.S. support, enabled the formation of a pro-American government in Lebanon that demanded Hezbollah’s disarmament.

Finding itself in a weakened state, Hezbollah has stopped responding to Israel’s targeted strikes, which occur roughly once every one to two weeks. The group’s leadership fears that it would not survive another full-scale confrontation with Israel.

Hezbollah’s reorganisation

It would be a mistake to think that Hezbollah has been defeated or broken. Its position has changed. Before the last war with Israel, the group effectively functioned as Lebanon’s deep state, with the country’s political life largely dependent on its decisions. That is no longer the case. However, Hezbollah still maintains control over southern Lebanon, which has effectively become its own mini-state.

Within the government, its representatives have retained influence, particularly in the financial sector. Of the 24 ministers, five are linked to the Shiite community and to Hezbollah to varying degrees, including Finance Minister Yassine Jaber. During discussions of government plans to disarm the organisation, these ministers demonstratively walked out of the session. Hezbollah has declared that it has no intention of surrendering its weapons — and the Lebanese army lacks the means to challenge it.

Hezbollah is restoring ties with Iran and building alternative routes for weapons supplies.

Although these routes are inferior to the former Syrian channels, the organisation is gradually rebuilding its military infrastructure. It is developing units specialised in the use of drones and precision weapons — Iranian-made guided missiles with fibre-optic guidance. This creates new capabilities and represents a serious threat to Israel.

If Hezbollah succeeds in creating a “wall of drones” and deploys them en masse against IDF forces and Israeli rear areas, it could paralyse the whole of northern Israel and, in the longer term, the country’s entire economy.

During the 2023–2024 war, drone strikes and unguided rockets already turned border areas of Israel into wastelands up to 15 km deep. If the strike zone expands to 50–100 km, the consequences would be catastrophic.

The organisation is also strengthening its underground infrastructure and tunnel systems, and expanding the Radwan unit, intended for raids behind enemy lines — analogous to the Palestinian Nukhba unit that carried out the 7 October raid.

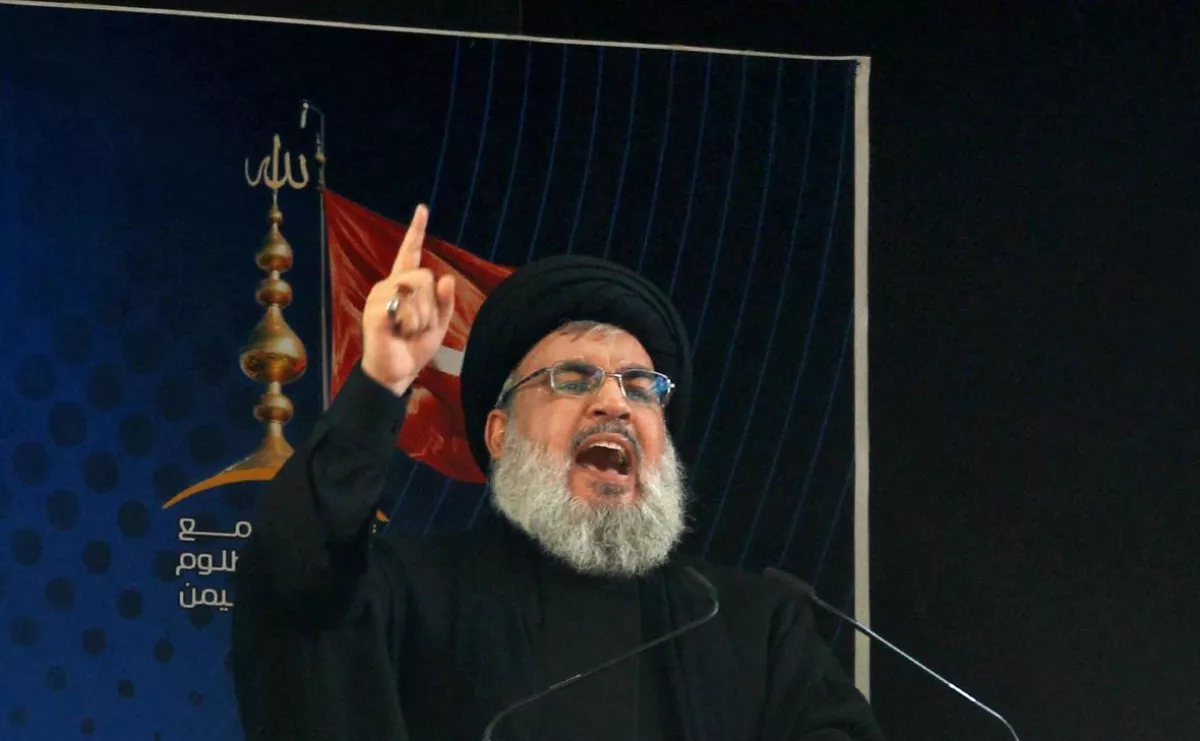

Internal changes are taking place within Hezbollah. After the death of Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah and his closest associates, various factions have emerged within the organisation, engaging in more open debate over strategy. This could lead either to internal fragmentation or to greater flexibility and unpredictability.

Hezbollah has gone underground, avoiding public statements and large-scale military actions. Yet this silence is deceptive: in the future, the group — with its resources, structure, and experience operating as a quasi-state — may well reassert itself.

Israel, for its part, has not ceased its military operations against Hezbollah, merely reduced their intensity. The question is not whether Hezbollah will strike Israel — but when it will happen.