Sikhs under Indian oppression Baku supports historical justice

On January 16, under the auspices of the Baku Initiative Group, Azerbaijan will host the country’s first international conference dedicated to the repressive policies of the Indian government against ethnic minorities. The event, titled “Racism and Violence against Sikhs and Other National Minorities in India: The Reality on the Ground,” is expected to feature the participation of Ramesh Singh Arora, Minister for Human Rights and Minority Affairs of the Pakistani state of Punjab, representatives of Sikh communities from Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States, heads of think tanks, scholars from foreign universities, as well as individuals who have directly suffered from India’s repressive and discriminatory policies.

The issue of persecution and oppression of Sikhs by India has so far not received proper international recognition or condemnation. Nevertheless, despite the absence of any significant resolutions denouncing the actions of the Indian government, the Baku Initiative Group has considered it its duty to support the Sikhs in their efforts to convey the truth about the mass repressions to the international community, seek acknowledgement of their tragedy, and draw attention to the need for legal and moral assessment of these events.

Before British colonisation, Punjab was a region governed by Sikh states known as Misls (sometimes spelt as Misal), which were later unified into the Sikh Empire under Maharaja Ranjit Singh. After its defeat in the Second Anglo-Sikh War in 1849, the empire was dismantled, and the territory was incorporated into the Punjab Province of British India.

From 1849 until the end of colonial rule in 1947, Sikhs remained an important but numerically dispersed community. During the negotiations over India’s independence, three forces had to be taken into account: the Indian National Congress (INC), the Muslim League, and the Sikh party, Akali Dal. Realising that creating a separate Sikh state was impossible, the Sikhs supported the INC, trusting its promises of federalism, autonomy, and minority protection.

However, after the Congress agreed to the partition of India, the Sikhs became among the main victims. The INC abandoned its earlier commitments, claiming that circumstances had changed. Much of the Sikhs’ fertile land remained in West Punjab, and hundreds of thousands were forced to flee—around 40% of Sikhs became refugees, while a portion of the population perished in the ensuing violence. Sikh representatives even refused to sign the Constitution of India, viewing it as a violation of the promises made to them.

After India gained independence, Sikh demands for the creation of Punjab as a single-language state (Punjabi Suba) were ignored for a long time. Authorities feared that such a move would strengthen Sikh identity. Unlike other regions of India, where linguistic reorganisation proceeded relatively peacefully, in Punjab, resistance was strong and accompanied by political pressure and threats. It was only in 1966—under the influence of the war with Pakistan and prolonged protests—that Punjab was created, albeit in a reduced form and with significant limitations.

Notably, Sikhs played a major role in India’s struggle for independence and suffered tremendous losses, yet after 1947, they were marginalised. The strengthening of centralised power resembled colonial governance methods: the state responded to protests not through dialogue but with force, treating them as a “law and order” issue. Government efforts to integrate Sikhs into the Hindu legal and social system were seen as measures of assimilation.

The attempt to weaken and “dilute” Sikh identity had the opposite effect. State pressure, violence, and the disregard of political demands only strengthened feelings of alienation, radicalisation, and conflict in Punjab, the consequences of which were felt for decades.

In 1973, the Sikh political party Akali Dal introduced a resolution demanding autonomy for Punjab and the transfer of certain powers from the central government to the states. The INC-led government regarded this document as separatist and rejected it.

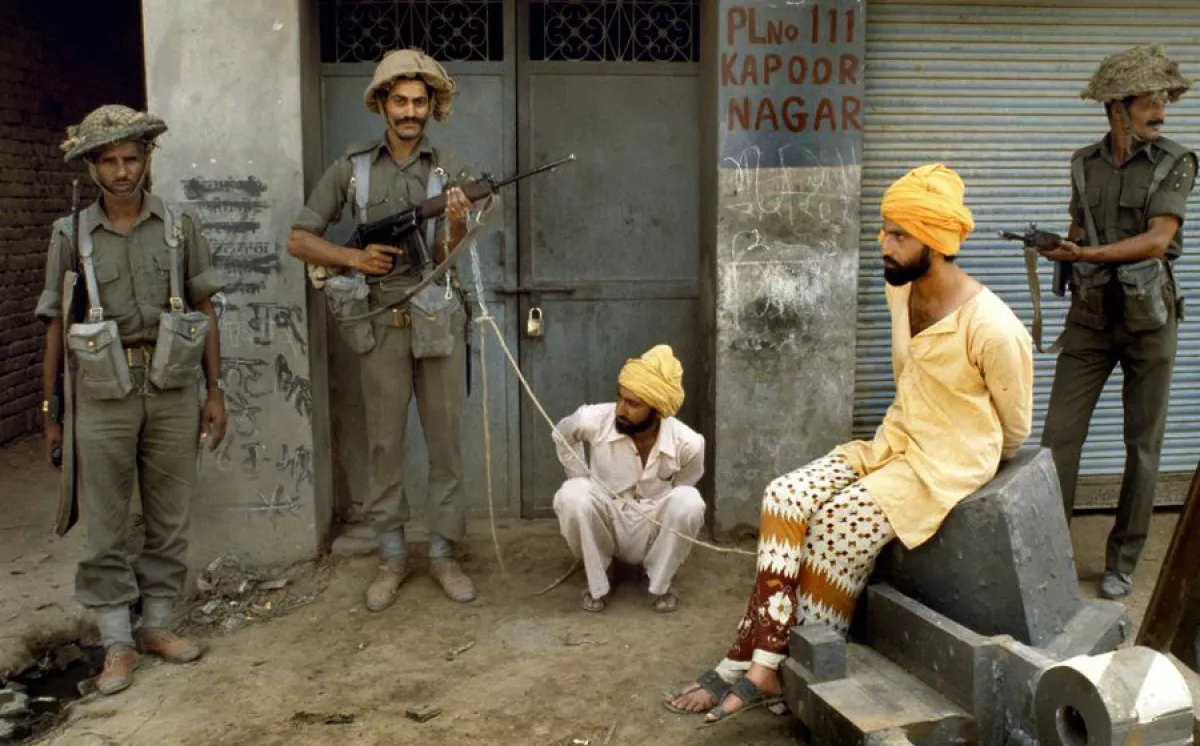

Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, an influential Sikh leader from the Damdami Taksal organisation, joined the Akali Dal and in 1982 organised protests aimed at implementing the 1973 resolution. Harsh police measures and large-scale repression by the central government affected a significant portion of Punjab’s population. In response, some Sikhs resorted to violence, which escalated the conflict and contributed to the radicalisation of Sikh youth.

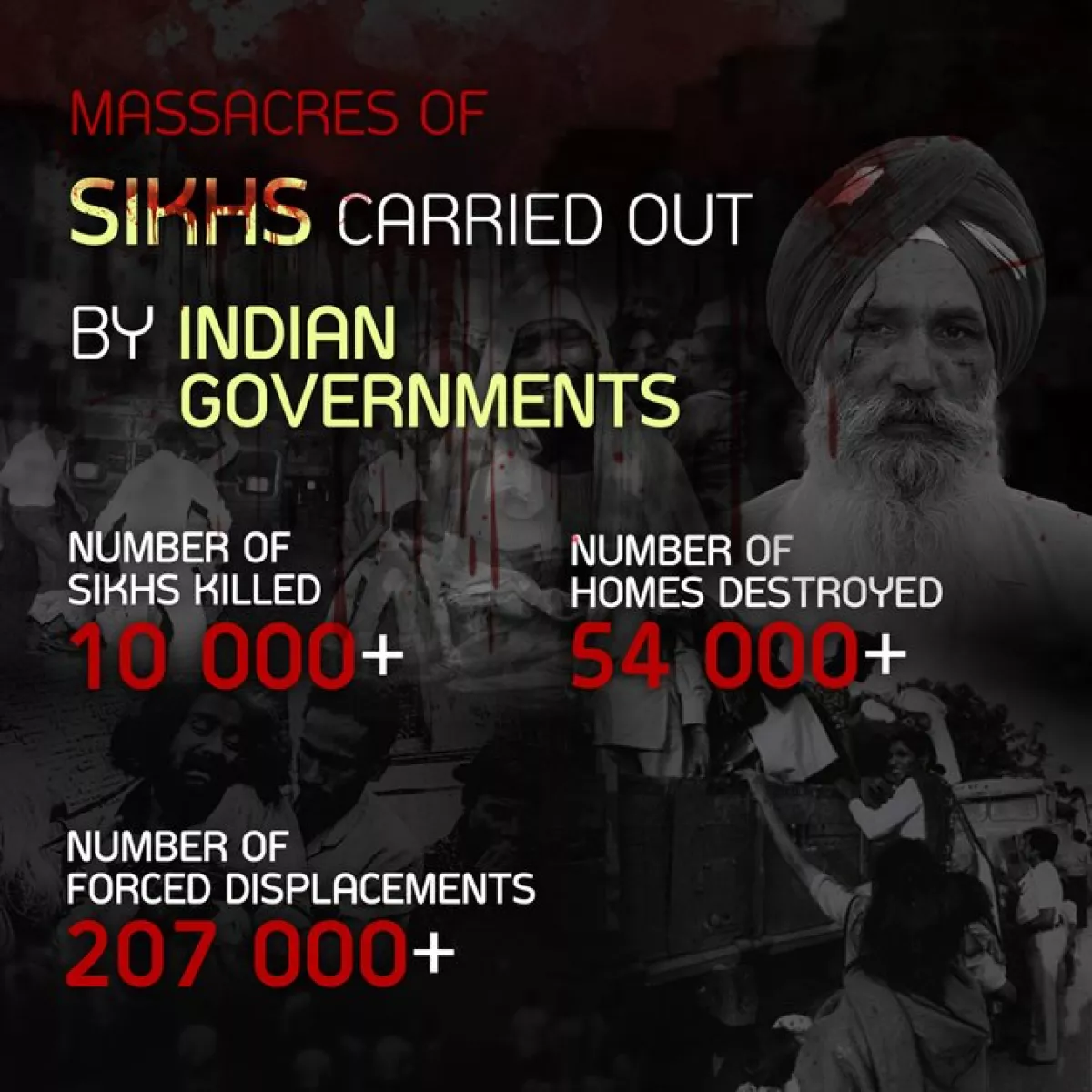

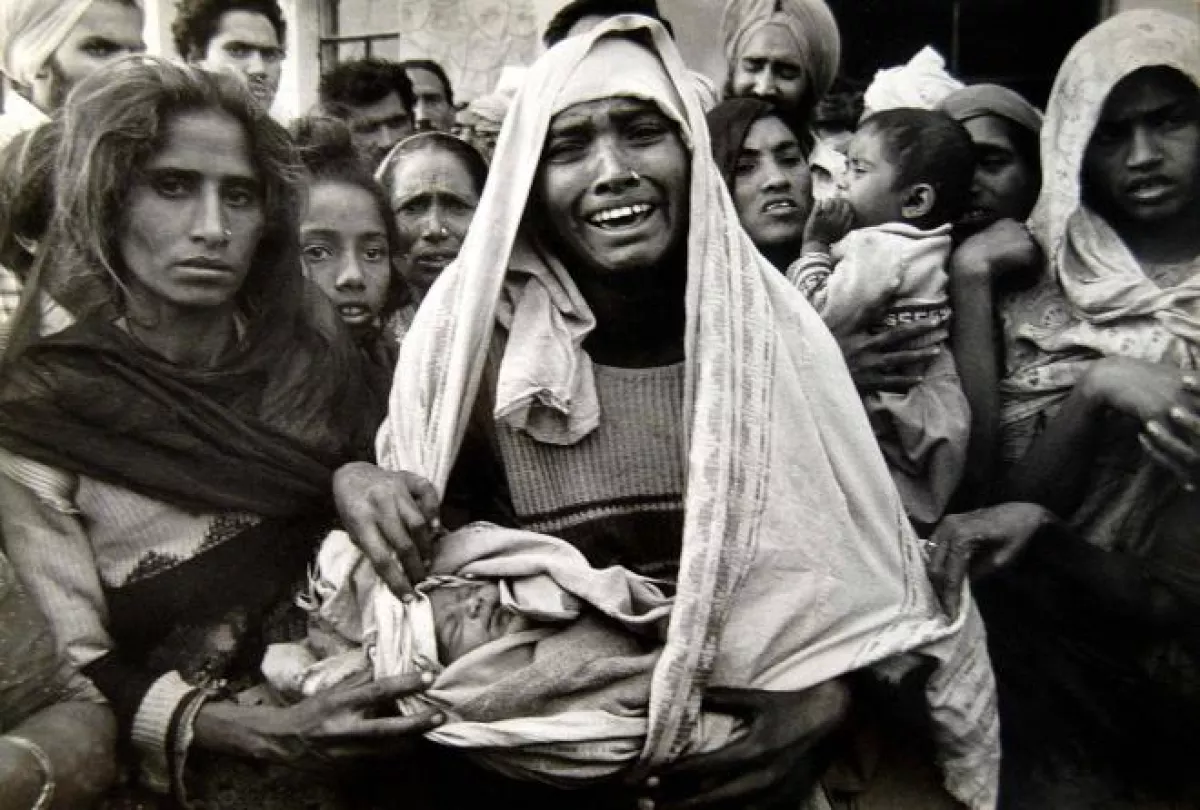

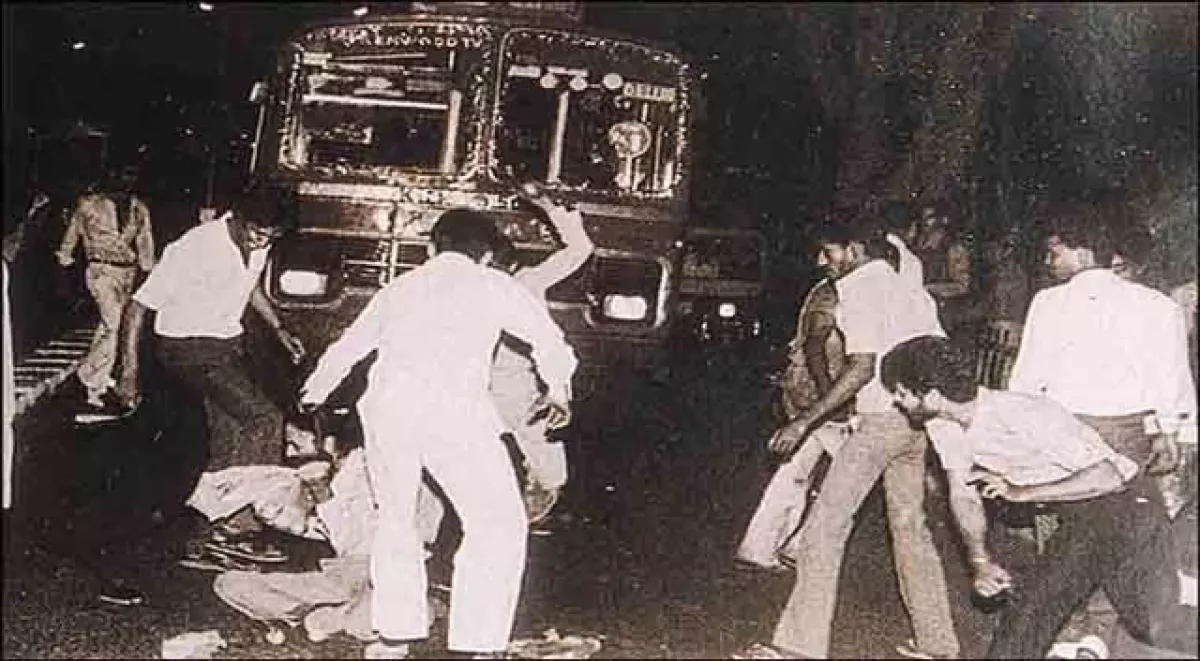

On October 31, 1984, India’s Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was assassinated. The following day, anti-Sikh pogroms erupted, lasting for several days in various districts. Between 10,000 and 17,000 people were killed, and the homes of more than 54,000 Sikhs were destroyed. Areas most affected included Sultanpuri, Mangolpuri, Trilokpuri, and other districts across the Yamuna River. Attackers used iron rods, knives, clubs, and flammable substances such as kerosene and petrol. They entered Sikh neighbourhoods, killed people indiscriminately, and destroyed homes and shops. Armed mobs stopped buses and trains, dragging Sikh passengers out for lynching; some were burnt alive, while others were doused with acid.

Such large-scale violence would not have been possible without the complicity of law enforcement agencies. Instead of maintaining order and protecting citizens, the Indian police fully supported the rioters, who acted under the direction of politicians such as Jagdish Tytler and Hari Krishan Lal Bhagat. Criminals were released from prisons and instructed on how to “teach the Sikhs a lesson.”

Human rights organisations, such as ENSAAF, have documented the involvement of high-ranking political leaders—mainly from the INC—in organising the violence, emphasising that the pogroms were not spontaneous but carried out with the use of state machinery.

Over the years, the Indian government has established more than ten commissions to investigate these events, but all have been criticised for their lack of transparency and ineffectiveness. Moreover, under the rule of Narendra Modi’s nationalist party—the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which systematically infringes on the rights and religious sentiments of national and religious minorities—the situation of the Sikh community has become even more dire.

In this context, tomorrow’s conference organised by the Baku Initiative Group takes on special significance, creating a real opportunity to bring the plight of oppressed Sikhs in India to the international stage and ensure objective and impartial coverage of the issue.

By Ramil Alaskarov