The end of “South Ossetia” Tbilisi eliminates Soviet legacy

The ruling party Georgian Dream has decided to abolish the administrative-territorial unit established in 2007 by former President Mikheil Saakashvili on the territory of the former South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast. The government institution is set to be officially liquidated on January 1, 2026, according to an announcement made on November 17, 2025 by Shalva Papuashvili, Speaker of the Georgian Parliament. Papuashvili noted that several legislative initiatives have been developed in consultation with the government, and the Parliament of Georgia plans to adopt the corresponding amendments by the end of the year.

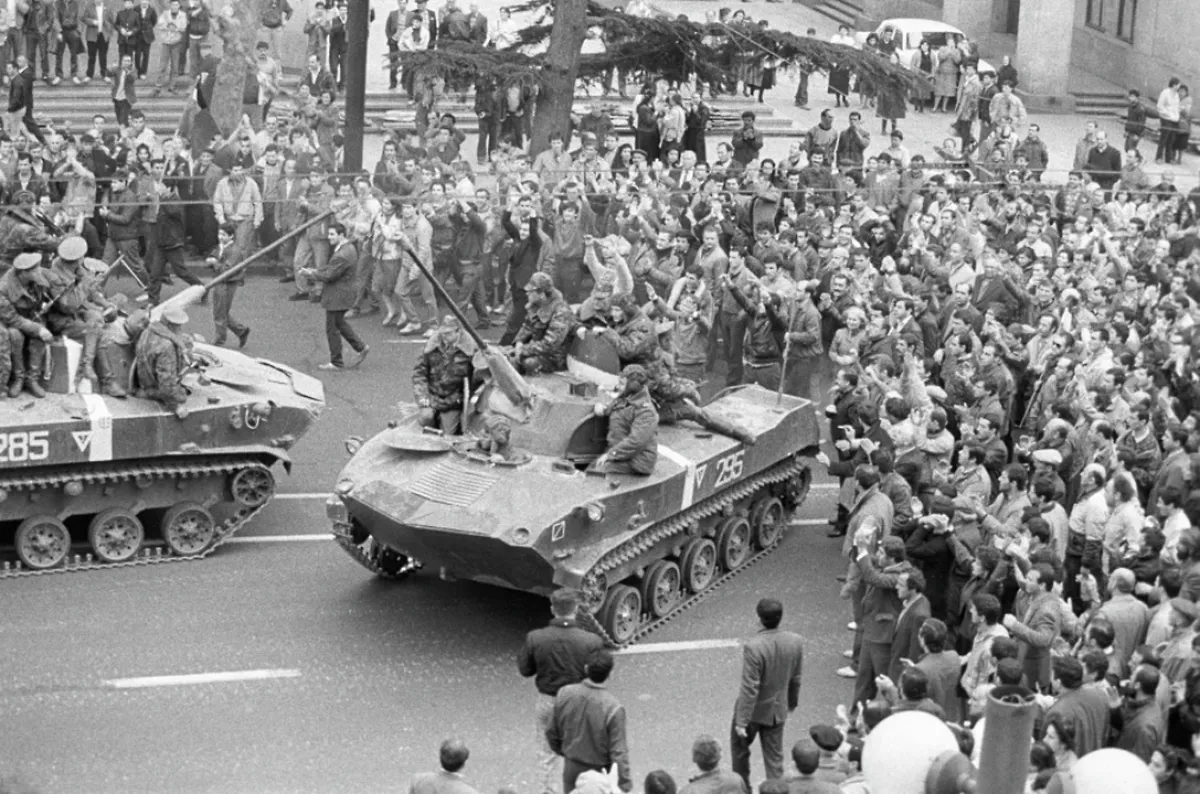

The Georgian authorities’ decision to dismantle this administrative entity is historic. Few Soviet-era administrative-territorial formations in the South Caucasus have been as detrimental as the so-called “autonomous oblasts.” In the region, there were two such formations: the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) within Azerbaijan and the South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast (SOAO) within Georgia. Both of these autonomous oblasts became epicentres of bloody separatist wars, leaving a lasting impact on regional stability.

First of all, both the NKAO and the SOAO were entirely artificial creations. In history prior to the establishment of the USSR, there never existed any state or administrative formations called “South Ossetia” or “Nagorno-Karabakh,” let alone ones organised along ethnic lines. In the territory of Karabakh, there existed an Azerbaijani state formation — the Karabakh Khanate. However, the NKAO, created by the Bolsheviks, was deliberately “carved out” from the historical Azerbaijani region of Karabakh with a convoluted border designed to ensure the relative dominance of the Armenian population — descendants of settlers from the Russian Empire era, who had assimilated the remnants of the Christian communities of historic Caucasian Albania.

Similarly, the SOAO was also “artificially carved out” — from fragments of various historical Georgian lands, as well as from at least four districts of the former Tiflis and Kutaisi governorates of the Russian Empire. The borders were drawn in such a way that an administrative unit with a minimal Ossetian ethnic majority was created across several economically isolated valleys and gorges. And since there was no significant settlement that could function as a “capital” for Ossetian communities, the town of Tskhinvali — inhabited by Georgian and Jewish populations — along with nearby Georgian villages, was included in the new formation.

Analysing subsequent historical developments leads to a sobering conclusion: both “autonomous oblasts” were created as a sort of “time bombs,” designed to “detonate” in the form of separatist conflicts at a certain point. There were simply no historical, economic, cultural, geographic, or any other objective reasons for their establishment.

It is telling that when, in 1987–1988, Armenian nationalists in the NKAO launched the so-called “miatsum” (unification-ed.) movement — aimed at annexing Azerbaijani territories to Armenia — the SOAO remained relatively quiet. At that time, Armenian nationalists actively tried to sway Georgian public opinion in their favour, “promising” Georgia parts of Azerbaijani lands. During mass rallies in Yerevan and Khankendi, against the backdrop of beatings, killings, and the expulsion of ethnic Azerbaijanis from the Armenian SSR and NKAO, as well as during the Sumgayit events and immediately after, Armenian political activists did everything possible to gain Georgian support for “miatsum”, portraying the events as “defending Christian brothers from the threat of a new genocide.”

A large-scale anti-Turkish campaign was directed at Georgian society. Emissaries from Armenia attempted to organise rallies in Georgia in support of the “Armenian people’s right to reunification,” operating mainly through “Georgians” of Armenian descent who had previously changed their surnames to Georgian ones.

However, the Georgian intelligentsia did not yield to the provocative attempts to drag the Georgian people into a geopolitical adventure. At the end of 1988 and the beginning of 1989, separatist movements in Abkhazia and the SOAO were “activated” — this time directed against Georgia itself. These projects were largely organised along the same lines as the “miatsum” movement and were coordinated from a single centre. Meanwhile, local Armenian communities, particularly in Abkhazia, quickly abandoned the notion of “Christian brotherhood” with Georgians and supported the separatists.

For the organisers of the “miatsum” project, separatism in the SOAO held particular value because, like the NKAO, it had the status of an autonomous oblast. In this way, an important political and legal precedent was being created for the future separatist “artsakh” project on the territory of the NKAO.

In response to the actions of the “South Ossetian” separatists, on December 11, 1990 the Supreme Council of Georgia abolished the South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast. Similarly, on November 26, 1991, in response to the actions of Armenian nationalists and separatists in Karabakh, the Supreme Council of Azerbaijan passed a law abolishing the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO). After that, no attempts were made in Azerbaijan to create any “alternative” authorities linked to the abolished autonomy — despite the severe consequences of the First Karabakh War and the long-term occupation of Azerbaijani territories.

The autonomous oblast, as an ugly administrative formation of the Soviet period, was permanently erased from Azerbaijan’s administrative-territorial structure. In 2020, Azerbaijan achieved victory over the occupiers and separatists in the 44-day war, and by 2023 the last remnants of the separatist enclave on the territory of the former autonomous oblast were eliminated: the so-called “artsakh” was destroyed once and for all, including by decisions made by the separatist leaders themselves.

In Georgia, however, in 2006–2007 there was an attempt to “restore” the abolished SOAO, which, as expected, produced no positive results.

“I would like to remind the public that in November 2006, on the initiative of the ruling United National Movement party, unconstitutional elections were held in the Tskhinvali region, resulting in the announcement of the so-called ‘President of South Ossetia’ and the formation of the so-called alternative government of ‘South Ossetia.’ With this step, the authorities at the time indirectly legitimised separatist processes, which constituted an outright and serious betrayal of Georgia’s state interests.

A few months later, in June 2007, again in violation of the Constitution, an ‘administration of a temporary administrative-territorial unit’ was established, based on the same unconstitutional ‘alternative government.’ This decision artificially restored the administrative borders of the South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast abolished in 1990, which later became one of the factors contributing to Russia’s military aggression in 2008 and the occupation of Georgia’s historic region of Samachablo.

It is now clear that these decisions were part of a geopolitical game by external forces, in which Georgia was assigned the role of a ‘sacrificial pawn.’ The policies implemented under Saakashvili’s leadership led to the escalation of the situation in the region and ultimately to war,” — stated Shalva Papuashvili, Speaker of the Georgian Parliament.

Thus, the necessity of abolishing the administrative-territorial unit created on the territory of the former South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast was obvious. All the more so because the mere existence of such a structure effectively “legitimised” the concept of the so-called “South Ossetia” in the eyes of the international community, which formed the basis of the entire separatist project. This is why it seems strange that representatives of the pro-Western opposition seek to portray the decision to abolish even a symbolic reminder of the former SOAO as supposedly “pro-Russian,” when in fact it fully aligns with Georgia’s national interests.

In reality, Russia itself, which occupies the region, appears unsure of what to do with the territory of the former SOAO. The region is entirely subsidised: maintaining it merely drains the Russian budget without yielding any return. The upkeep of military bases in the occupied Tskhinvali region has become a serious problem for Russian military leadership — especially given that Moscow’s resources, attention, and funding are required on the Ukrainian front.

Russia is forced to spend funds maintaining an awkward administrative formation that hinders the establishment of normal relations with Georgia and the development of mutually beneficial transit through this territory. This is the inevitable outcome of the separatist project implemented on the territory of the former Soviet-era autonomous oblast.

The primary victims of this situation are the Ossetians themselves: their so-called “independent state” has become a poor economic and logistical trap, where the population lacks employment and stable income, access to proper healthcare is limited, and the cost of goods is significantly higher than in the Russian Federation. The process of total depopulation of the former autonomy continues.

Of the nearly 100,000 people who lived in the territory of the SOAO during the Soviet period, only about 15–17,000 remain in the Tskhinvali region today — mainly in Tskhinvali itself and around the Russian military bases. Most Ossetian villages have been completely abandoned. Their revival, without the de-occupation of the region and its economic and logistical reintegration with the rest of Georgia, appears extremely unlikely.

By Vladimir Tskhvediani, Georgia, exclusively for Caliber.Az