Fear as a tool Unfulfilled predictions of an “Azerbaijani attack”

In recent years, a persistent rhetoric has been forming within the Armenian expert community, according to which Azerbaijan could allegedly start a new war against Armenia at any moment. This topic regularly arises, accompanied by references to foreign policy events, internal reforms, diplomatic contacts, or regional conflicts.

In each specific period, a new "reason" for panic is sought — whether it be environmental summits, delegation visits, events in the Middle East, or internal political instability. However, the essence remains unchanged: an attempt to portray Baku as a state that supposedly will inevitably resort to "aggression." At the same time, as is not hard to guess, these accusations are not supported by facts, nor by real dynamics on the border, nor by official statements that could indicate preparations for war.

A telling example is the spring of 2024, when a whole wave of similar statements was timed to the upcoming COP29 climate summit scheduled to be held in Baku. Some Armenian analysts then suggested that Azerbaijan would allegedly "seek to resolve territorial issues after the summit to strengthen its negotiating position." This thesis quickly spread on social media and among English-speaking expert circles but ultimately proved to be unfounded. COP29 has long since concluded, and the predicted attack did not occur. However, instead of revising their assessments, some commentators simply shifted the narrative.

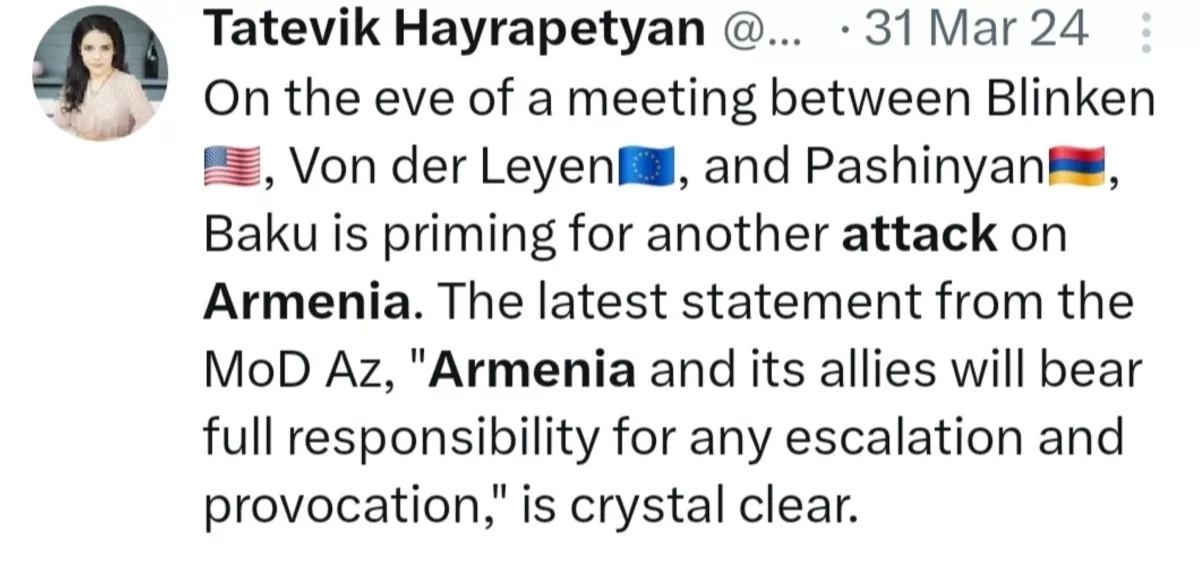

In March 2024, former Armenian parliament member and APRI Armenia analyst Tatevik Hayrapetyan claimed that “on the eve of a meeting between Blinken, von der Leyen, and Pashinyan, Baku is priming for another attack on Armenia.” She cited a statement from the Azerbaijani Ministry of Defence, which said that “Armenia and its allies will bear full responsibility for any escalation and provocation.” Hayrapetyan presented these words, spoken against the backdrop of an increasing number of Armenian provocations, as proof of “Baku’s aggressive intentions.”

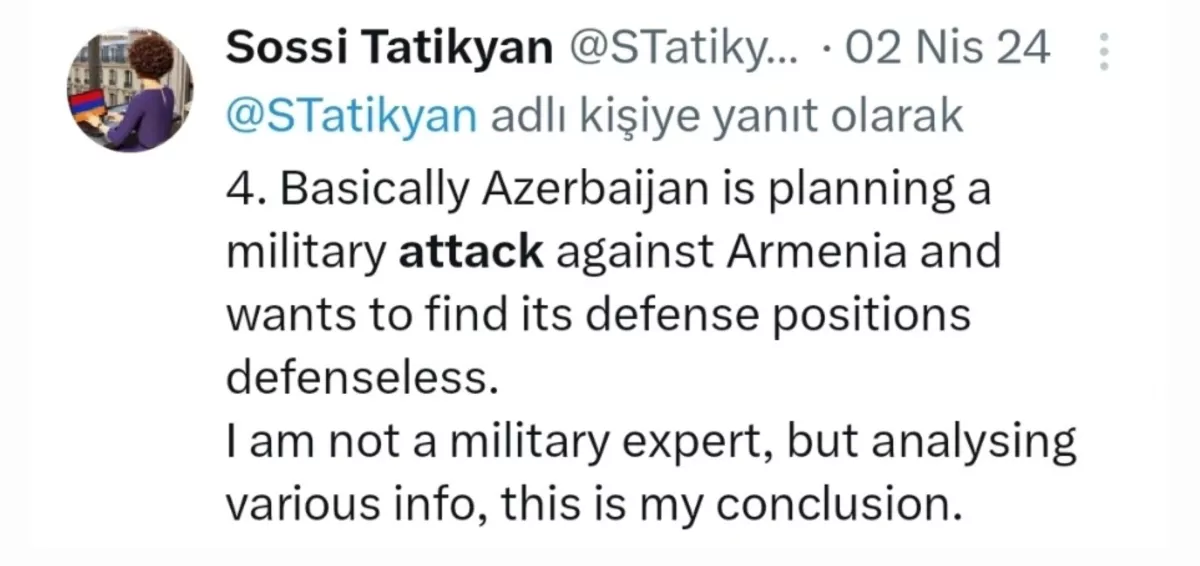

In April, former diplomat Sossi Tatikyan joined this rhetoric, stating that Azerbaijan was allegedly planning a military attack and seeking to find vulnerabilities in Armenian defenses. Notably, Tatikyan openly admitted that she lacked military experience but nevertheless did not question her conclusions. Her statement was actively circulated in English-language media feeds despite the absence of any specifics or factual basis.

In January 2025, the topic of an “inevitable attack” resurfaced once again, this time in the form of an analytical report authored by Nerses Kopalyan titled “Why Aliyev Thinks He Has to Attack Armenia Soon.”

The work, published as part of the EVN Security Report, was presented as a study of the potential causes of military escalation but was actually based on speculative assumptions, emotionally charged interpretations, and deliberate distortion of the political context. No facts were provided to indicate that Azerbaijan was preparing for aggression. However, the headline and the overall emotional tone of the report once again set a framework of perception in which any action by Baku is interpreted as a precursor to war.

As Turkish commentator Könül Şahin notes, such narratives emerge with remarkable regularity. They appear in the media space almost every week—sometimes as tweets, sometimes as interviews, sometimes as “expert reports”—but always follow the same logic. According to her, when the scenario around COP29 failed to materialise, the next one was introduced: that Azerbaijan allegedly intends to exploit the escalation between Iran and Israel for its own purposes. This rapid shift in narrative essentially points to a predetermined agenda: accusations must be voiced regardless of the external context, irrespective of the situation on the Armenian-Azerbaijani border.

Of particular interest is who spreads these claims. Some of the authors of such statements are associated with the Armenian authorities and operate within a pro-government agenda. Their task is to increase international pressure on Azerbaijan, portray Armenia as the vulnerable party, and gain support from Western capitals by playing the role of a “victim of possible aggression.” For these purposes, any statement from Baku—even the most neutral—is interpreted as a threat. Sometimes, it is enough for Baku to say that it reserves the right to respond to provocations. That alone is enough for the Armenian information environment to start talking about a forthcoming war.

However, this rhetoric is also actively used by experts opposed to Pashinyan. Their motivation is different: they seek to undermine the very idea of making peace with Azerbaijan, presenting it as a pointless and dangerous step. Their argument follows this logic: if Baku supposedly intends to wage war anyway, then any peace initiatives only weaken the Armenian side. Thus, accusations against Azerbaijan become a tool in the struggle not against an external enemy but against an internal political opponent—Prime Minister Pashinyan and his course toward settlement.

A paradox emerges: diametrically opposed political forces in Armenia use the same tactic—accusing Baku of preparing “aggression.” Yet neither side presents facts capable of supporting their claims, while both achieve the desired effect: the information space becomes saturated with alarming signals that, through sufficient repetition, begin to be perceived as credible.

An illusion of threat is created where none exists in reality. This strategy relies on a classic technique: fear is instilled not through events but through propaganda language. It is no coincidence that many such statements take the form of expert opinions, amplified by headlines using words like “attack,” “inevitability,” “strike,” or “escalation.” Meanwhile, the reality on the ground is ignored: the level of tension on the border remains fairly stable, and the topic of a potential peace agreement remains on the agenda.

Thus, accusations against Azerbaijan have long since gone beyond mere reaction to events and become part of a political technology. This is not analysis, but a tool—of pressure, distortion of reality, and influence on the audience, primarily international. It is no longer expert activity, but deliberate disinformation aimed at distorting perception and substituting facts.