Kazakhstan at a political reset Experts weigh in on constitutional overhaul

As is well known, a constitution is the fundamental law of a state, holding the highest legal authority and establishing the foundations of its political, legal, and economic system. Over time, however, and in light of a country’s development as well as evolving international circumstances, this key legal framework may require updating. Such a step is currently under consideration by one of the largest countries in the post-Soviet space: the Republic of Kazakhstan.

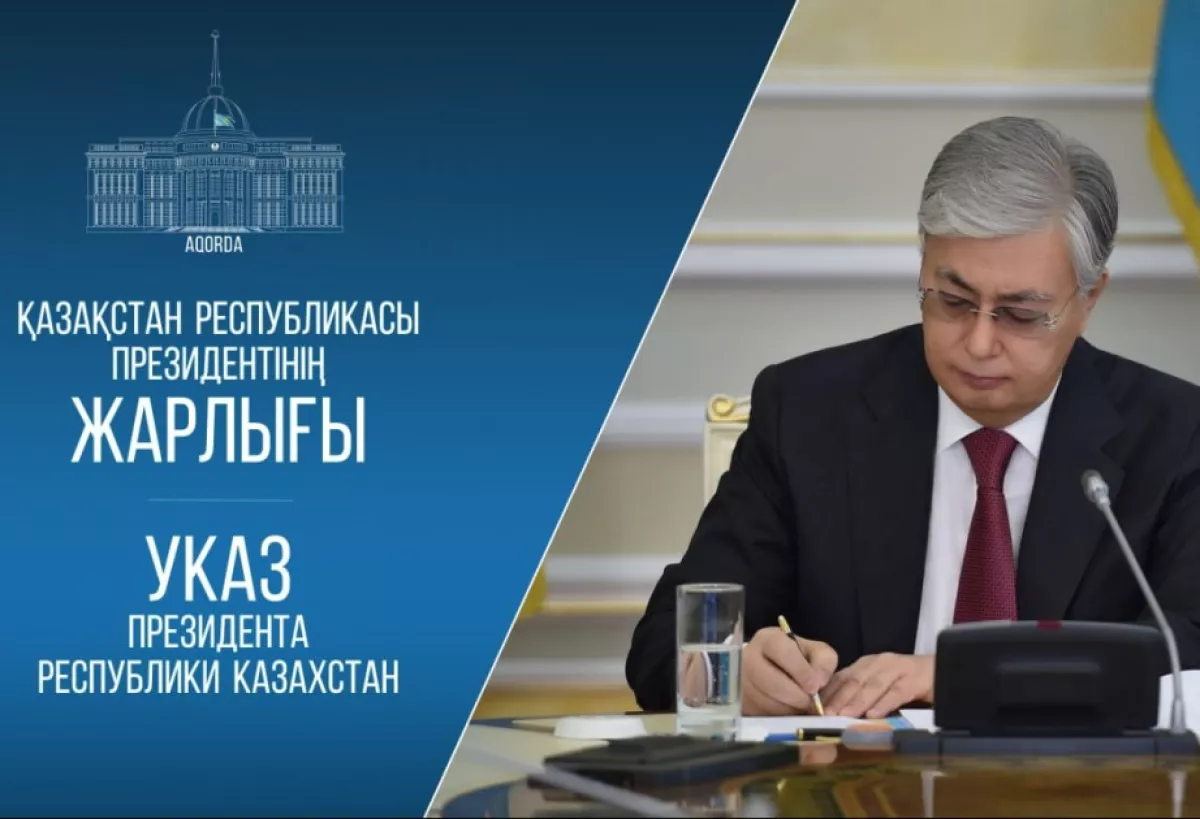

Thus, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev signed the corresponding decree and scheduled a referendum on constitutional amendments for March 15, 2026. Commenting on this measure, he noted that the adoption of the amendments would give a “powerful impetus to Kazakhstan’s development and help unlock the potential of every citizen.”

“Kazakhstan is definitively moving away from a super-presidential form of governance and transitioning to a presidential republic with a strong, authoritative parliament. The proposed changes naturally continue this process. Together with the political transformations of recent years, including the 2022 constitutional reform, they raise the issue of the need for a complete reset of Kazakhstan’s constitutional foundations,” the head of state said at an expanded government meeting.

Notably, among the key changes are the transition from a bicameral parliament to a unicameral model and the formal establishment of the Constitution’s supremacy over international treaties. Meanwhile, despite conflicting media reports, the status of the Russian language is not changing and remains unofficial.

What do people within Kazakhstan itself think about the proposed amendments to the Basic Law? Kazakh political scientists respond to this question for Caliber.Az.

According to candidate of political sciences Sharip Ishmukhamedov, the essence of the constitutional reform is to continue the reforms that have already begun, to affirm the irreversibility of changes in the country’s political system, and to sustain the process of strengthening the republic’s sovereignty and independence. However, a detailed examination of the constitutional reform process shows that it does not have a single, unambiguous direction.

“On average, the country adopts a new Constitution about every decade and revises the substance of its core provisions. In this context, one can recall the adoption of the first Constitution of independent Kazakhstan in 1993, which established the state as a presidential-parliamentary republic with strong judicial and legislative branches. In 1995, a second Basic Law was adopted, creating a presidential system that dominated the three branches of government. By the early 2000s, the consolidation of presidential power had reached what could be described as an absolute level. Major changes followed in 2019 and 2022 after political conflict and the revolutionary events known as ‘Bloody January,’ as a result of which a presidential-parliamentary model of governance was once again established in the republic.

The introduction of constitutional amendments this year continues the process of changes that began in 2019, strengthens and clarifies them, and, in my view, consolidates the powers of the current leadership, providing an opportunity to retain authority in the hands of the post-Nazarbayev elite, which has chosen a path of transforming the country while trying to avoid the mistakes of the past,” said the political analyst.

He noted that, according to the new draft of the Basic Law, a unicameral parliament will replace the bicameral system and will be called the Kurultai, while the concept of “values” is introduced and broad powers are granted to the country’s president.

“The main values of Kazakhstan, now set out in Article 2, are sovereignty, independence, unity, and territorial integrity. Regarding traditional values, a new article establishes that marriage is a voluntary and equal union between a man and a woman—a provision similar to those adopted in Russia in 2020 and Belarus in 2022. In addition, the country will introduce a new state institution—the People’s Assembly—which will convene once a year to discuss any changes and amendments to the Basic Law, as well as issues of public concern.

In my view, a distinctive feature of this constitutional reform is that its discussion is taking place within a very narrow timeframe—citizens were given only 22 days to analyse the text of the new Constitution. This will be followed by a referendum, the dissolution of parliament, elections to a new legislature, and, most likely, early presidential elections. The factors driving Kazakhstan toward such sweeping restructuring of the state system include certain external and internal challenges, as well as serious economic and political problems in the country, which require the presence of newly elected representatives with a fresh perspective in parliament and a new presidential term capable of governing the country over the next seven years.

In my opinion, the most important of all the innovations is the position of vice president, which provides clear guarantees for maintaining the current course of the government in the event that something happens to the head of state due to force majeure or irreversible circumstances. This also involves a number of political considerations, such as Russia’s proximity and its level of influence on Kazakhstan’s political system, as well as other external factors,” said Ishmukhamedov.

In turn, political analyst Olzhas Amirzhanov believes that the package of constitutional amendments will reshape its foundations, but this process is necessary and reflects the political realities in which the country finds itself today. It will also make the Basic Law more flexible and centralised in the hands of the executive branch, while creating a transparent system for parliamentary work, making it more agile and dynamic.

“The new unicameral parliament will consist of 145 deputies, whereas the current bicameral system has 148 legislators. According to the statements made, the powers of the parliament will be expanded. At the same time, Kazakhstan is bringing back the institution of vice president (abolished in the 1990s by Nursultan Nazarbayev), who will be appointed by the president with the consent of parliament. If the deputies reject the appointment twice, the head of state will gain the right to dissolve Kurultai.

On the other hand, the presidential vector is also being strengthened. For example, the Kurultai does not receive additional powers in forming the government, and in its absence, the president will have the authority to issue acts at the level of constitutional laws. In addition, the primacy of national law over international law is being established—a very important point, since the current Constitution does the exact opposite. Overall, in my view, all amendments aimed at changing the articles of the Basic Law are being introduced with one crucial goal: to ensure the country’s security and prevent external forces from undermining the levers of power,” concluded Amirzhanov.