India: 300 million protest against Modi’s government Workers, farmers, and students unite

Trade unions and farmers’ organisations in India have led one of the largest strikes in human history. It is aimed against labour legislation, a new rural employment law, as well as trade agreements with the US and the EU.

According to trade union leaders representing the organisational platform “Central Trade Unions” (CTU)—an umbrella structure uniting India’s key unions—around 300 million workers, farmers, students, and professionals joined the nationwide strike on February 12.

The massive mobilisation brought thousands of coal mines, oil refineries, factories, and transportation networks to a standstill. The protests were actively supported by the Samyukt Kisan Morcha (SKM) and the All India Agricultural Workers’ Union (AIAWU), who organised demonstrations in district centres and rural areas. The All India Kisan Sabha (AIKS) hailed the day as a “historic success.”

The protesters’ key demand is the repeal of four new labour codes passed by Narendra Modi’s government. Trade unions consider these codes “contrary to the fundamental interests of the working class.” They are also calling for the repeal of the Viksit Bharat Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission (Gramin) (VB-GRAM G) law, which replaced the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) of 2004. Organisers insist on restoring the previous legal framework, which guaranteed at least 100 days of subsidised work to millions of rural families.

Strike participants have also rejected India’s recently signed free trade agreements with the United States and the European Union. According to them, the deal with Washington represents a “complete capitulation of the country” and could “undermine the foundation of the rural economy,” as it allows the unrestricted import of foreign agricultural products, thereby increasing competition for domestic producers.

At a rally at Jantar Mantar in Delhi, Centre of Indian Trade Unions (CITU) president Sudip Dutta described the one-day strike as largely symbolic, warning that if Modi’s government fails to address the protesters’ demands, “it should be prepared for longer and more widespread actions.”

In July 2025, trade unions staged another major nationwide strike, mobilising an estimated 250 million people. Such actions are usually confined to a single day, and even strong statements from union leaders seldom translate into significant pressure on the ruling authorities.

A significant aspect of the protest has been the defence of the “secular” and “democratic” character of the Indian Constitution. Trade unions, farmers’ movements, and leftist parties—including Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI (M)), Communist Party of India (CPI), and Communist Party of India (Marxist–Leninist) Liberation—accused the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) of “inciting religious hatred against Muslim and Christian minorities” and carrying out an “unprecedented assault on democratic dissent.” According to them, this includes the arrests of hundreds of activists, union leaders, scholars, and journalists under sedition laws.

Notably, Marxist-Leninist groups—ideologically inspired by the experiences of Stalinist USSR and Maoist China, states known for large-scale repression and systemic human rights violations in the 20th century—are today defending civil rights and freedoms in India. While this stance may appear paradoxical, many of the social and political issues they highlight are indeed real and pressing.

Under the leadership of Hindu nationalist forces from the ruling BJP and its allies, India has sustained robust economic growth, at times exceeding six per cent annually. The country’s strategy is centred on the so-called “Gujarat model,” in which the state provides substantial incentives and subsidies to two major conglomerates owned by entrepreneurs close to Prime Minister Narendra Modi. These corporations, together with other large and small private companies, play a key role in the scientific-industrial modernisation, industrialisation, and urbanisation of the country.

They develop seaports and airports, oil refineries, roads, and telecommunications networks, and implement numerous infrastructure projects. Through these initiatives, India is effectively building an infrastructure base that strengthens centralisation and consolidates the modern state.

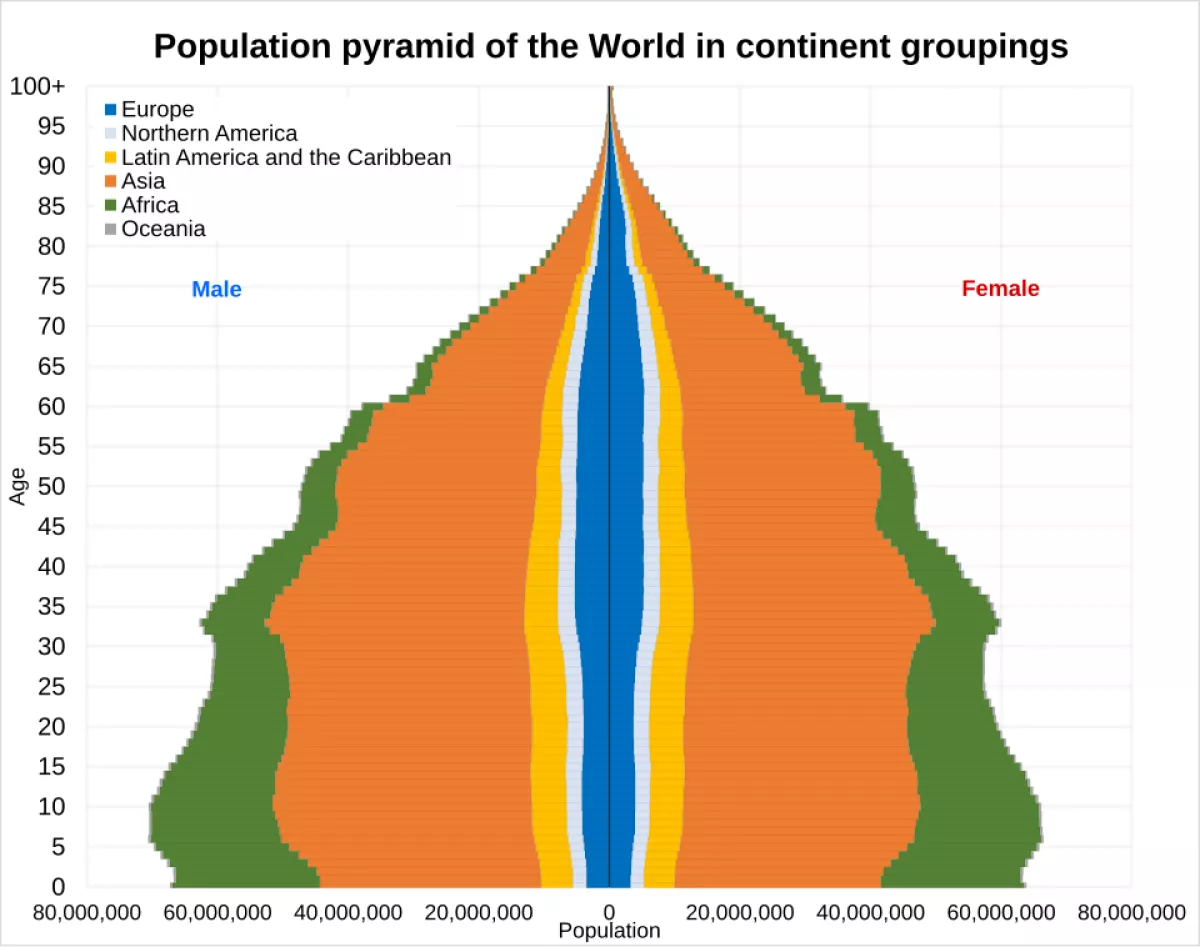

While some Western countries debated the “decline of industry” and the “disappearance of the working class,” China, India, and other countries of the Indian subcontinent—home to around 3.5 billion people, roughly 40 per cent of the world’s population—have steadily transformed into global manufacturing hubs, while simultaneously investing in science and education.

Nonetheless, India still faces significant challenges. More than 60 per cent of the population continues to live in rural areas, with many farms dependent on government subsidies. The Modi government is pursuing liberal reforms in the agricultural sector, gradually reducing support to increase the competitiveness of Indian farmers on the global market and to encourage their transition to urban industry, where labour productivity is higher.

However, this approach carries the risk of bankrupting millions of farms and their families, exacerbating existing social inequality and widespread poverty. These conditions fuel social and class-based protests. During previous waves of demonstrations, farmers have clashed with police and temporarily blocked parts of New Delhi.

At the same time, the government has mechanisms to stabilise the situation.

Firstly, there is the ideology of Hindutva—a blend of religious fundamentalism and nationalism. This politico-religious concept effectively excludes around 200 million Muslims from the notion of a “unified Indian nation,” whose population approaches 1.5 billion. This exclusion fuels communal tensions. At the same time, India remains a strong centralised state with an extensive security apparatus capable of suppressing large-scale protests.

The BJP represents only the top layer of this system. Beneath it are numerous Hindutva-affiliated social organisations spanning different aspects of public life: cultural associations, youth movements, and paramilitary structures. Interfaith tensions between Hindus and Muslims often shift the public agenda away from socio-economic issues toward cultural and religious conflicts, in a manner similar to the “culture wars” in the United States.

Secondly, trade unions serve as a stabilising factor. Despite the presence of some radical factions, the union movement as a whole is generally oriented toward negotiation and institutional conflict-resolution mechanisms. Protest activity is typically limited to one-day strikes and consultations with authorities, which reduces the likelihood of uncontrolled escalation.

This approach reflects the nature of union structures, which rely on a professional apparatus of officials, lawyers, organisers, and managers. Their role is to mediate between labour and business, conduct negotiations, and participate in governmental arbitration and legal proceedings. The ultimate goal is usually a compromise formalised through legally binding agreements.

Trade union leadership, which manages funds and organisational infrastructure, has a direct interest in institutional stability. Its socio-economic position typically differs from that of rank-and-file workers, reducing the likelihood of support for radical scenarios.

As a result, unions act as a brake on revolutionary developments—such as the establishment of collective self-governing bodies or the takeover of enterprises and territories, as occurred in several countries during the 20th century. India’s union structures are closely integrated into the judicial and ministerial systems and, in the foreseeable future, have little incentive to operate outside these institutional frameworks.

With two key tools at its disposal—ideological mobilisation based on Hindutva and institutionally embedded trade unions—the government retains the ability to pursue a strategy that combines support for big capital with accelerated industrialisation and urbanisation. One-day strikes serve as a “safety valve,” while interfaith conflicts divert public attention toward identity issues.

Nevertheless, the rule of Narendra Modi and the BJP faces growing structural risks. Widespread rural impoverishment and rapid urbanisation—a process that can be described as proletarianization—are concentrating millions of poor people in cities. Under conditions of high social tension, even a localised crisis could trigger large-scale destabilisation, as seen under comparable socio-economic circumstances in several countries during the second half of the 20th century.